home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

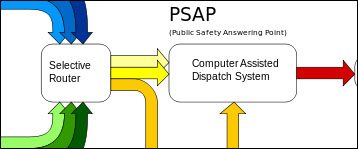

Dispatchers in the Okanogan County sheriff’s office navigate work stations that include six monitors, three computer mice and two keyboards apiece. The Okanogan County dispatch team is unusually seasoned: half of the 12-member staff has been on board 10 years or more. Photo courtesy of Mike Worden Dispatchers in the Okanogan County sheriff’s office navigate work stations that include six monitors, three computer mice and two keyboards apiece. The Okanogan County dispatch team is unusually seasoned: half of the 12-member staff has been on board 10 years or more. Photo courtesy of Mike WordenEmergency Nature When you or a Methow valley neighbor picks up the phone to dial 911, operators are indeed standing by—but maybe not in the spot you imagined. They’re not at the Aero Methow headquarters in Twisp, nor at any of the three Fire District 6 stations around the valley. Instead, a team of 12 dispatchers rotates round-the-clock shifts in the county sheriff’s office in Okanogan. Surrounded by six monitors apiece and equipped with a couple of headsets each, dispatchers (usually two to four on any given shift) answer 911 calls and broadcast the radio signals, pages and texts that trigger local emergency responders into action. How heavily do local crews rely on the Okanogan dispatch center for fast, efficient communications? Even when an in-person emergency—a person with a broken arm, say, or a bleeding cut—bursts in the Aero Methow doors, “The fastest thing we can do [to mobilize a response] is call 911,” says agency executive director Cindy Button. Most calls for help land at the dispatch center mid-day, between the hours of 11:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. That’s when most people are up and about, “…regardless of the shift they worked or what drug they were using over the weekend,” speculates Okanogan County Chief of Special Operations Mike Worden. Last year, his office fielded more than 20,000 calls—the most in its history.

At the same time the dispatcher is calmly walking a caller—often agitated and fearful—through those emergency medicine steps, she’s radioing local police, fire, and/or Aero Methow teams to swing into action. Toned Out As radio tones ring out at emergency stations or offices around the valley (each emergency base has its own distinctive set of beeps), on-call volunteers and staff are receiving pages and texts at home and at work. These texts track and label the emergency-response process in a distinctive shorthand that permeates the emergency frequencies. “It’s a whole other language to learn,” observes Button. For instance: “ACK” signals not frustration, but rather confirms that a tone has been ACKnowledged. Volunteer firefighters take an extra step. They call an 800 number to acknowledge their pagers and find out how many others have responded. Why? There’s a time-saving app for that: En route to the station, district commanders and chiefs can check their smartphones to see exactly which of their volunteers will be on hand. They can plan their crew assignments in advance, rather than waiting until everyone assembles at the station. But it’s not all 21st-century technology. When they jump into a GPS-equipped SUV, ambulance or fire engine, local police and crews are also carrying paper backup: a 172-page map (plus addenda) that the county prints each year. Complete with topo lines, it shows even primitive roads—“anything with a house,” says Button. Radio Free Methow Those Okanogan-sent radio signals land first at a tower on McClure Mountain. From there, signals ping-pong up the valley from one repeater to the next. Division Chief Brian McAuliffe has been with Fire Department 6 for almost 20 years, and remarks on the “greatly improved cell phone and radio coverage” he’s seen over that time. Now that there’s a repeater in Mazama, fire crews can stay in direct communication with the Okanogan dispatchers, even from Lost River. After the tragic Thirtymile Fire in 2001, when county radio traffic was so thick that it was hard to get a word in edgewise, Aero Methow got its own repeater equipment and radio frequency. Now the local crew can talk amongst themselves, without competing for airspace with the county agency. The Future in Texts Possibly as early as next year, predicts Worden, citizens will be able to text 911. A pilot project rolled out in Tennessee last fall, and the FCC is gradually expanding the service. A text uses less cellular signal than a voice call, points out Worden, and is thus better-suited for many emergency situations. The communications chief also looks forward to days of greater connectivity, when Methow valley emergency vehicles might be equipped with laptops (as Omak police cars are today). In the meantime, it’s social media to the rescue for curious citizens. In Okanogan, Worden is hatching plans to buff out his department’s website and launch a Facebook page. Closer to home in Twisp, Button is set to launch a blog that will offer behind-the-scenes glimpses of a day in the life of Aero Methow. 3/8/2013 Comments

|