home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

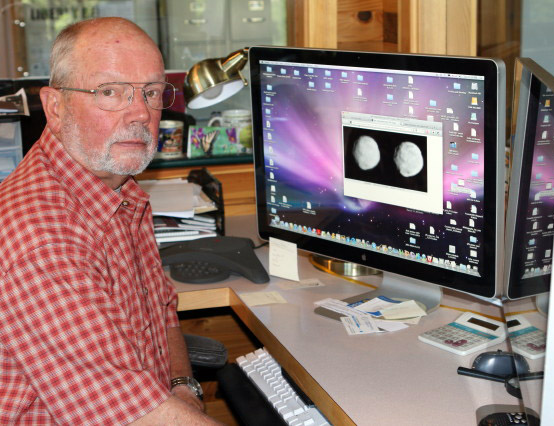

Deep Science, Deep Woods 7/17/2013: McCord wins NASA highest honor. more >> Thomas

B. McCord has worked

on the icecap in Greenland and on top of Mauna Kea on

the volcanic Big Island of Hawaii. But when it came

time for this distinguished physicist to find a new

place to pursue cutting edge space science, improbable

as it may seem, he chose a secluded, forested hillside

in the Methow.  From

his office up the Rendezvous, Thomas B. McCord, director

of the Bear Fight Institute, tracks NASA's Dawn spacecraft

mission, which he founded, to Vesta, a "dwarf

planet" twice as far from the sun as Earth. Dawn

is now 140,000 miles from its late-July meeting with

Vesta and will follow its orbit around the sun for

a year before moving on to explore Ceres. From

his office up the Rendezvous, Thomas B. McCord, director

of the Bear Fight Institute, tracks NASA's Dawn spacecraft

mission, which he founded, to Vesta, a "dwarf

planet" twice as far from the sun as Earth. Dawn

is now 140,000 miles from its late-July meeting with

Vesta and will follow its orbit around the sun for

a year before moving on to explore Ceres.“It really is a pretty place,” he says of the Methow Valley. “It doesn’t wear thin.” When

he decided to leave the University of Hawaii for the

Methow with his wife, Carol, in 2002, “We sold the

car, we sold the house, the dog died and we came here

because we already had a house here,” says McCord, who

bought property in the Methow in 1991 on a first-time

visit to friends. “The valley actually is far richer than people think,” says McCord, commenting on the diversity of interesting, accomplished but not always well-known people who have made it their home. Its geography is open, “not just two walls,” he adds; there are lots of private spots like his in which to settle. There may be no better example of how worldwide linkups have been made possible in isolated rural areas by the internet revolution than McCord’s Bear Fight Institute, which sits on 100 forested acres up the Rendezvous. From there he accesses a secure server at Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he’s a Distinguished Visiting Scientist, and keeps tabs on the space missions he’s involved in. Lately, those have been the Cassini-Huygens to orbit Saturn, Mars Express to orbit Mars, Rosetta to study a comet up close, and the Chandrayaan -1 moon mission led by India. On that one, “We discovered water on the moon,” says McCord. McCord is 72, so he’s been involved in many more. He and the instruments he’s designed have played a significant role in space discoveries. He correctly predicted the composition of lava flows on the moon before astronauts got there, and he discovered that salty minerals cover much of Europa, Jupiter’s moon. When he began his career, telescopes were the big thing for studying space. Later his specialty became designing spectrometers that use light to reveal the composition of surfaces on planetary and other objects. Forty years ago he deduced that Vesta, which was thought to be an asteroid, was really what some scientists now call a “dwarf planet.” McCord – and, among others, his colleague and now Rendezvous neighbor John Adams - detected its “basaltic” composition, which means it has melted. So it had to have had heat inside, which rules out an asteroid, according to McCord. It took him 15 years to persuade NASA to go look, and today he’s monitoring the voyage of the Dawn spacecraft from his office in the Methow woods as it approaches a first-of-its kind meeting with Vesta. After Vesta, Dawn will link up with Ceres, which McCord says interests him even more because of the likelihood that there’s “a lot of water on it.” Tiring of university administration duties, he wanted to do his own thing but had questions about whether the institute approach would work: “If you build it, will they come? Will NASA continue to fund an eccentric old man living in the wilderness?” Yes, on both counts. The institute is housed in a large, renovated house with several offices and banks of high-speed computers. Bookshelves are filled with tomes on astronomy and science, and the walls decorated with t-shirts and posters memorializing many of the NASA missions McCord has worked on. He grew up in rural Pennsylvania and was the only member of his high school graduating class to attend college. His father liked science, and his mother taught him to shoot. He likes to hunt, fish and play the piano. While serving in the Air Force McCord had an “epiphany” that he wanted to become a physicist. At first this meant solid state physics, but he became intrigued with space exploration. That took him from a tenured professorship at Massachusetts Institute of Technology to the University of Hawaii, where, as a recognized expert on telescopes, he was asked to renovate the famed Mauna Kea telescope. McCord and Carol, who was its president, previously owned a firm that produced hardware and software for imaging systems. The Department of Defense was among its clients. McCord designed an early version of some of the sensing instrumentation used on current Air Force drones as well as imaging systems that provide views of submerged coral reefs and croplands, for example. McCord still proposes space missions to NASA after researching their justification and feasibility. The six full-time employees at the institute are joined from time to time by other scientists and post-graduate students interested in exploring the surfaces of solar system objects and how to develop the information needed to launch space missions to research them. “Is it too far? What is the payload? What instruments do you need? Are they feasible? What does it cost?” are among the questions the students are trained to research, says McCord. Asked to name his most exciting project, McCord says, “I like mentoring young people.” About 25 of his doctoral students now compete with him for NASA contracts, he laughs. “You foster your own demise by creating grad students, and mine are really good. “I have great-great-grad students. It’s almost like a family reunion” when they all get together to work on the same projects, he adds. “That’s the most satisfying thing. I guess I’m the father of this whole field.”

|