home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

Bernie Bigelow's newest guitar is made from local apple wood, something he hasn't tried before. Bernie Bigelow's newest guitar is made from local apple wood, something he hasn't tried before.

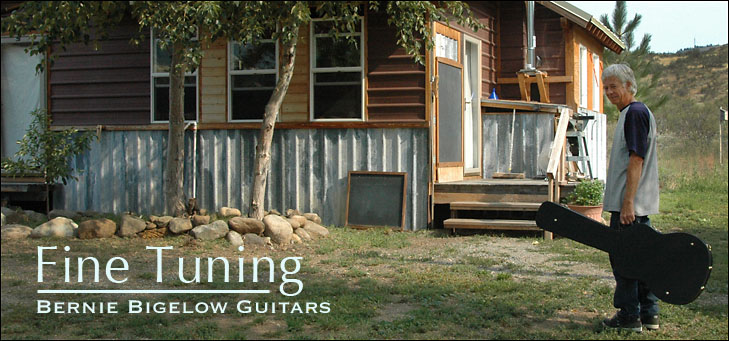

(luthier: maker of instruments) A piece of a maple tree that once stood on Burgar Street in Twisp is now the neck of a guitar hand built by Bernie Bigelow, a quiet luthier in the Methow Valley who has been turning out instruments for 17 years. The body of that guitar is from a Pateros walnut tree. And on the workbench in the Bigelow Guitars shop at the bottom of Libby Creek is the beginning of another instrument being made from slices of a local apple tree. “Finding and choosing the woods”, says Bigelow when asked if there’s one part of of the guitar making process he likes the most. “I often spread everything out and then select the combination for a particular instrument.” Mahogany, bubinga, rosewood, ebony and most recently cocobolo from Mexico are the other woods Bigelow has used for the bodies and necks of instruments. Guitar tops - a big part of the sound - are usually Sitka spruce from a small supplier in Southeast Alaska. From experience, Bigelow can now sense, by examining and tapping, if a piece of wood will work. “I can tell if it will resonate - if it will sing . . . or at least detect if it’s a dud or not.” Beyond that he never knows the final sound until all the incremental steps of assembling the instrument are complete and the first chord is strummed. Bigelow came to the Methow Valley in 1981. “I was moving to Vermont from Monroe, Washington,” he explains, “but only made it this far.” Before that he worked as a machinist in an Alaskan salmon cannery. The switch to wood, and instruments, came a few years after moving to the Methow when he decided to take a stab at resurrecting a guitar with a broken neck.  A new guitar side made of cocobolo wood and the device used to heat and bend it into shape. Because this wood is more brittle, which creates a unique tone, it's much more difficult to form. A new guitar side made of cocobolo wood and the device used to heat and bend it into shape. Because this wood is more brittle, which creates a unique tone, it's much more difficult to form.“As a machinist you’re always fixing things, so trying to repair the twelve string came naturally,” says Bigelow. “The advantage is knowing and being able to achieve tight tolerances.” He’s not alone - successful guitar companies like Taylor and Larrivee were also started by machinists. The tolerances matter. Just a 1/8” change in body depth can make “a big difference in tone”, says Bigelow. Less than a thousandth of an inch in adjustment can noticeably change how an instrument feels, something experienced players notice right away. To make that point Bigelow shows a neck joint that “probably needs about half a thousandth” shaved off to put it in perfect alignment. After his first run at repairing the twelve string guitar, Bigelow spent 10 years restoring and repairing instruments of all quality and condition. That, along with the local library, became his training ground. When an instrument sounded good or different, he tried to find out why - looking outside and in, tapping, listening, measuring. The lower quality student guitars let him practice the tweaks and fine adjustments that can make so much difference. "It was wonderful," remarks Bigelow, "I could make them easier to play."  Mother of pearl that will be inlaid, by hand, around the soundhole of a Bernie Bigelow guitar. Mother of pearl that will be inlaid, by hand, around the soundhole of a Bernie Bigelow guitar.

Bigelow built two guitars from kits and then got his first commission - an unexpected request to build a small, “parlor” size guitar. He started it in 1994 and finished in the fall of the next year. In the middle, realizing he was at the limits of his knowledge, he took a break and did a week of intensive study with a master luthier in northern California. One of the first things he learned there was that the guitar shape is not the best for good sound. But, because it’s what players expect, “we’re stuck with it” he says. “So, we work with everything else in the construction to improve the tone.” Bigelow has built about 45 guitars so far and has settled on three designs, two based on Martin guitar models and one of his own making - an acoustic influenced by a classic electric guitar called the Les Paul. “I wanted to build a small guitar but didn’t want a parlor size . . . I wanted to do something else. I love the Les Paul shape and started there”, explains Bigelow. “Then I worked with things like body size and depth, sound hole size, and where the neck joins” to improve the tone and feel. “I planned to keep the last one I built for myself,” he mentions, but a player smitten with the instrument persuaded him to sell.  The start of a guitar neck made of three different kinds of woods. The start of a guitar neck made of three different kinds of woods.

“That’s the encouraging part,” explains Bigelow, “when players like my instruments.” When he builds a guitar, tone and playability come first with fit and finish close behind. That becomes apparent as he watches someone trying out one of his creations. He studies how the person and instrument fit one another and seems to light up when one of his guitars comes back showing the wear marks of being played a lot. Bigelow creates no more than half a dozen instruments each year, more often just one or two. With each new one, he builds on the last. “I’m definitely experimenting all the time,” he says. “I still look forward to the next one.” It takes him about 80 hours, sometimes less, to turn out a new guitar, much of that time spent on the surprisingly difficult finishing step where multiple coats of lacquer are applied. He doesn’t build many instruments to order, preferring instead to create something new and then wait for it to find a good owner. Fans of Bigelow guitars seem to pick up on the wood combinations that add character and interest, making an instrument more enjoybable to both look at and play. His experimentation gets noticed as well, such as a small guitar with a slightly wider neck or a body size that adds depth to the sound paired with a wood that adds brightness. Even with just three basic models, no two instruments are really ever alike. “I’d rather build at my own pace,” says Bigelow. “It’s always better for someone to come in and discover what I have available.” Customers also seem to like knowing the builder and some have been content to specify only one aspect of a custom guitar - like 6 or 12 strings - and leave the rest up to him. Bigelow is also happy to share what he’s learned. Connor Hamilton and Steve Rawson - last names well known in the Okanogan valley - spent part of a summer building guitars under Bigelow’s guidance. And his brother came up once to try out the trade, took to it immediately (to his surprise) and is now building finely crafted guitars out of his shop in Reno, Nevada. “He’s a genius,” says Bigelow.  The maple and walnut back of one of Bernie Bigelow's guitars. The maple and walnut back of one of Bernie Bigelow's guitars.For such a hands-on craft, the internet has made a big difference for this Libby Creek luthier. Sources of instrument wood are much easier to find. Tips and techniques for building instruments are also much more available in part because of the willingness of luthiers to share what they’ve learned. “The Guild of American Luthiers”, for example, “is a great source of shared knowledge,” says Bigelow. “It’s amazing the information that’s available compared to when I was searching for help through the local library.” Most of Bigelow’s guitars sell in a year or less, mostly by word of mouth. They tend to sell more quickly if they are played out in public. Some fans also stop by from time to time to see what’s new and available. Bernie Bigelow may not be making a full living off the luthier trade, but he does seem to be making a life. In a small shop filled with tools from micrometers to milling machines Bigelow creates guitars in the ocean of guitars that are available these days. But these are Methow Valley guitars. And they make players smile.

9/30/2012 Comments

|

||||||||||||||||