home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

Looking for the Melissa  David James, professor of etymology at Washington State University,

talked about butterflies of the northwest region known as Cascadia. David James, professor of etymology at Washington State University,

talked about butterflies of the northwest region known as Cascadia.

The topic of butterflies lured about 50 people into the Methow Valley Community School Tuesday night for a talk by British-born David James, who is now a professor of entomology at Washington State University. With Dave Nunnalee, James wrote a detailed book about the growth stages of butterflies in ‘Cascadia', an area covering roughly Washington, Idaho, northern Oregon and southern British Columbia. James and Nunnallee have compiled their total 25 or so years of research into a book, ‘Life Histories of Cascadia Butterflies'. The men were working independently on similar butterfly research when they met in 2005 and decided to collaborate. Their co-authored book was published last year. The one butterfly James and Nunnallee could not find and rear is the Melissa Arctic. “Can we find it at Slate Peak?” was the burning question on Jame’s mind, he said, before he arrived in the Methow Valley and learned about the late snowpack, which means no luck this visit. “Many lepidopterists (butterfly experts) think of Slate Peak as a mecca,” said James. Rare butterfly species found at Slate Peak include Astarte Fritillary, Lustrous Copper, Vidler’s Alpine and Grizzled Skipper and maybe, just maybe, the Melissa Arctic.  Many butterflies make their way into the high Cascades during their life. In fact, Slate Peak is well-known among butterfly enthusiasts as a place to look.

Photo by David Nunnalee. Many butterflies make their way into the high Cascades during their life. In fact, Slate Peak is well-known among butterfly enthusiasts as a place to look.

Photo by David Nunnalee.

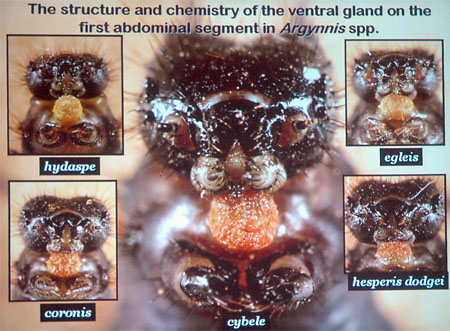

They had hoped to find an egg-laden Melissa Arctic female to take home where they could hatch the eggs and study and photograph the stages of the eggs, larvae and pupae, as they have with all the other species in their book “We reared and photographed 156 of our 157 (Cascadia) species,” said James. It turns out butterflies start as eggs, grow to be caterpillars, then go through four to seven stages of being a caterpillar before changing into pupae and then butterflies. The process can take nine days to two years, depending on the species. Some butterfly caterpillars have defenses not usually associated with beautiful fluttering butterflies—fangs, glands with volatile chemicals designed to smell bad to predators, and camouflage which changes according to what the caterpillar is eating. One species even builds ‘branches’ of its own feces to reside on, James said. Some caterpillars “have anti-freeze” - glycerol - in their bodies and can survive temperatures of twenty to thirty below zero Fahrenheit. James has looked into recovery of butterflies after fires, and found them to be very resilient. He said butterflies in one study made an “astounding recovery” in both diversity and abundance within two years of a major wildfire, almost back to pre-fire levels.  Not everything is pretty in the study of butterflies. Not everything is pretty in the study of butterflies.

James is running a program with the penitentiary in Walla Walls for inmates to rear monarch butterflies to help restore monarch populations. “They’re very interested and they have a lot of time,” he said. He said the survival rate of butterflies born at Walla Walla is very high. The main problem at the penitentiary, he said, is that the “big, tough, tattooed inmates” can’t make themselves squeeze the identification tags they are supposed to add to the butterflies wings tightly enough, so the tags tend to fall off. Still, he sounded proud of the program. He said it’s good for butterflies, for science, for the community and for the inmates. “It’s the ease of taking digital pictures that made this (book) a reality,” James said. The expensive and time-consuming system of film photography would have been a hindrance. The fact that they could catch adult females and raise their eggs, photographing the species through their growth stages also allowed the book, he said. Finding the eggs (instead of adult females) in the wild would not have worked. “We would be here for many decades.” David James’ next-to-last slide showed something he is proud of—a letter from famous naturalist David Attenborough, praising Life Histories of Cascadia Butterflies. The very last slide showed one of his young daughters with a butterfly on her nose. James’ talk on butterflies was one of the Methow Conservacy’s First Tuesday Lecture Series.

7/11/2012 Comments

|