|

Skier, Author, Farmer, Spy

Mazama's Doug Devin

by Karen West

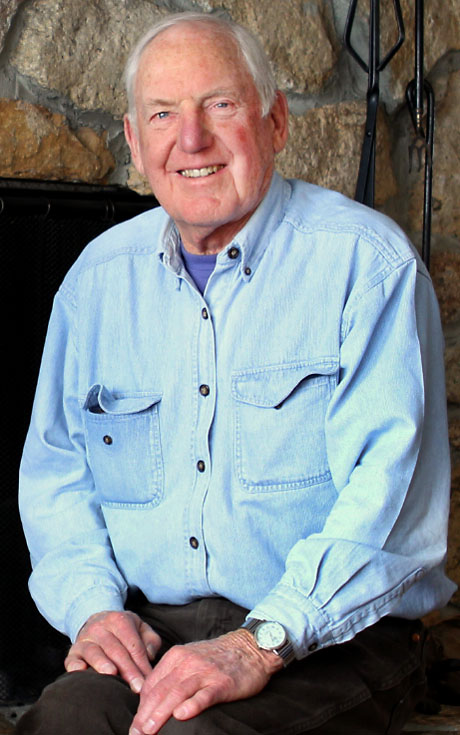

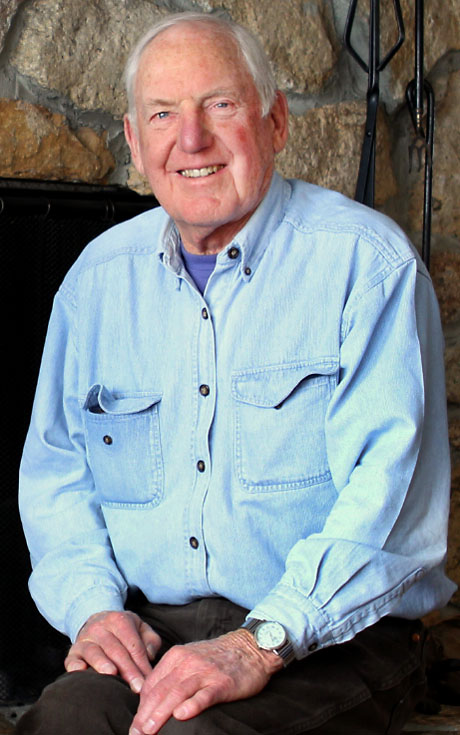

Doug Devin first started vacationing in the Methow Valley in the 1950s. Photo by Karen West

As a young boy growing up in Seattle, Doug Devin took advantage of a rare snowfall one winter by making himself a pair of skis from two pieces of interior-trim molding. He waxed the bottoms with paraffin, made toe-straps from strips of inner tube, slipped them on and slid down the hill outside his house - all the way to the end of the block - without falling.

"It was a wonderful feeling," he says, and it ignited his lifelong passion for alpine skiing.

Sitting in his cozy Mazama living room with a view up valley to Mt. Robinson, Devin shares stories from an extraordinary 85 years of life that have taken him from growing up as the son of Seattle's World War II-era mayor to working in Europe for the Central Intelligence Agency to raising cattle and alfalfa in the Methow Valley and, perhaps most infamously in these parts, to being a lead proponent of the ill-fated Early Winters downhill ski resort. Or, as he so diplomatically puts it, "an opportunity that didn't materialize."

A gracious and modest man who understates his role in every story and punctuates them with chuckles, Devin talks about the time he joined the University of Washington ski team but soon broke a leg. Because he was a photographer, the team kept him on the bus and assigned him to do publicity. Shortly after the leg mended, he fell and broke the other leg. He quickly points out that these broken limbs happened before releasing ski bindings were invented. Leg fractures were common among downhill skiers.

However, there was a silver lining for the young man on crutches. A fellow UW student and ski team friend named Grace Bovee carried his books across campus and opened doors for him. Some years later, he and Grace would be married in Europe while both were working for the CIA. And since Devin's photographic expertise helped him get his job, you might say those fractured legs had quite a legacy.

Growing Up

Devin recently completed a book of family history and stories from his own life to share with his family. In it he describes himself as a "shy boy" who was "very self-conscious around girls." (His only sibling was a younger brother.) However, by high school his father had been elected mayor of Seattle, which boosted his social status, and young Doug was becoming an accomplished photographer. He supplied high school sports photos to the Seattle Star, one of the city's three daily newspapers, which also published on page one a dramatic lightning-strike he photographed. And the Star included several of his photos in its coverage of the victory celebrations at the end of WW II. Years later his photographs of Governor Dan Evans reaching the summit of Mt. Rainier appeared in Time magazine.

Devin writes in his memoirs that by the time he was a junior at Roosevelt High School he'd "found the courage to talk to girls" and considered a young woman named Mary Maxwell his girlfriend. They remained friends even after she married Bill Gates, Sr. Yes, that Gates. Mary's son founded Microsoft.

Devin's dad, a World War I veteran and Seattle attorney entered politics in 1938. In a later race for mayor, Bill Devin challenged his opponent as a puppet of Teamster Union boss Dave Beck and won with two-thirds of the vote. He served for the next 10 years and steered Seattle through the tumult of WW II. He also became the first American municipal official to visit Japan after the war when he led a delegation to Hiroshima and pledged to help the Japanese people rebuild their city. His trips there laid the groundwork for what eventually would become Sister Cities International.

The CIA Years

Doug Devin joined the U.S. Marine Corps after high school graduation. Post-military service, he enrolled at the University of Washington, where he received a degree in economics and business in 1951. But his post-college plan was to find a way to get to Europe to ski.

"I went to Washington, D.C., and looked for a job that would send me there," he says. "Somebody told me about this agency, so I went to 2430 E Street. There were no signs on the door or anything ... I went in and told them I was applying for work. I filled out endless forms and was told they might have something for me but that it would take awhile."

That "agency" was the new CIA, which hired Devin and sent him to Frankfurt, Germany to microfilm documents for the biographical and industrial section files. This "was at the peak of the Cold War," he says. One case took him to a British-occupied location on the Rhine River where Devin was assigned to an office in Villa Hugel, the 269-room mansion at the Krupp family estate built by the steelmaker Alfred Krupp in the late 1860s and early 1870s. Devin, who lived in a smaller house on the grounds, was there to microfilm records related to coal and iron production. The Krupp family was one of the world's principal steelmakers. The last member of the dynasty to live at Villa Hugel was Alfried Krupp, who was convicted of war crimes for using "slave" labor to manufacture armaments for the Nazi war machine. Another assignment took Devin to the U.S. Embassy in Athens, where he filmed copies of a Communist Party newspaper that contained "the names and numbers of all the players."

Grace, who parlayed her degree in communications into a job with the CIA in Europe so she could ski, was stationed in Austria. Devin says Grace's job was more important than his and paid more. She was the CIA's first woman in Salzburg and ran a one-person communication's office. The couple married there in 1953 at the city's only Protestant church with their ski and CIA friends in attendance. But because everybody signed the guest book, it was promptly confiscated by the local CIA security officer and declared "secret" because "...it contained the real names of all the CIA personnel in Salzburg."

Devin downplays his CIA work, saying it consisted mostly of gathering information with a camera or microfilm or teaching others how to do it. He says America's spy efforts were not very sophisticated at the time he was in Europe. "The Americans ... were so gullible and wanted information so bad." The U.S. government had lots of money and everybody in Salzburg had something to sell, he says, adding that a lot of money was paid to local people, but many of the recipients were "double agents."

Grace and Doug Devin at their wedding dinner in the Alpina Hotel in Salzburg, Austria. Their CIA and skiing friends attended the ceremony. Grace's mother sent her a wedding dress. Photo courtesy Doug Devin. Grace and Doug Devin at their wedding dinner in the Alpina Hotel in Salzburg, Austria. Their CIA and skiing friends attended the ceremony. Grace's mother sent her a wedding dress. Photo courtesy Doug Devin.

The Ski Business

When Grace became "heavy with child" the couple quit the CIA and came home to America. "One of the important contacts I made over there [in Europe] was with a family-owned ski boot company [Haderer]," Devin says. He became their North American representative, one of several jobs he would have in the ski industry. Alpine skiing was becoming a very big deal in the U.S., and Devin started Seattle's first speciality ski shop - the Sporthaus. He also was a sales representative for the A&T Ski Company.

Devin credits two developments with fueling the downhill ski rage - the invention of releasing bindings, which cut the number of leg fractures and made the sport safer, and the invention of a stretch fabric for ski clothing that made women look stylish on the slopes. "It became a social sport as well as exercise," Devin says. But working in the ski industry was keeping him on the road much of the time and his income wasn't enough to comfortably support his family.

In the late 1950s, brothers Frank and Joel Pritchard hired Devin to help manage Bank Check Supply, a small specialty printing firm. The banking business was moving from hand-processing customers' checks to automated machines that could scan customer account numbers on pre-printed checks. Millions of people had to be persuaded to use checks that had their names and account numbers printed on them. Bank Check Supply designed lines of attractive checkbook covers and checks and sold them to the banks. Devin greatly expanded the company's business and stayed with it until he moved to the Methow Valley in 1970.

Doug and Grace Devin continued to ski and work as ski instructors while they lived west of the Cascades. Both were active in the development of the Crystal Mountain ski area. Their children, Steve and Betsy, both married and living in the Methow Valley, raced for the U.S. National Ski Team when they were young and raised their own children to be skiers as well.

The Methow Dream

The Devin family started vacationing in the Methow Valley in the 1950s, when it was a six or seven hour drive from Seattle. By the time they bought a cabin in 1964, the legendary wilderness packer Jack Wilson and his wife, Elsie, were important figures in their lives. In the mid-1960s Wilson was adding cabins to his Early Winters Resort near Mazama and thinking about how to create a year-around business. Devin says Wilson wanted to build a ski lift out back. His idea was to keep the cabins full in the winter with guests who could snowshoe, downhill ski and go on sleigh rides.

A bumper sticker seen often in the Methow Valley when a destination ski area was proposed for Sandy Butte near Mazama. Courtesy of Doug Devin.

In his book "Mazama - The Past 125 Years," Devin wrote: "The hill behind the cabins where Jack was considering putting a simple lift had only a few hundred feet of vertical drop and would not justify anything more than a beginner hill ... We got out maps and began looking at other possibilities. We found that around the corner there was a north-facing hill called Sandy Butte with 4,000 feet of drop and variable terrain. This appeared to be too good to be true."

"The other thing we got excited about," Devin says in an interview with Grist, "was it was all private property at the bottom." He had friends who knew the ski business, and they knew that to affordably build a destination ski area, they would have to buy property for it "before the speculators came in and ruined everything." Thus a group of local valley boosters and ski area representatives formed the Methow Valley Winter Sports Council.

Devin says that about the same time, the Schafer family, which had a grazing permit on U.S. Forest Service land for Blackpine Basin and all of the Goat Peak area, wanted to move their cattle business to the Columbia Basin, where winters were milder. The Early Winters project bought the Schafer ranch, and the Devins, along with local cattleman Gary Belsby, bought some of the cattle and took over the Schafer's range permit. "We bought a number of places" through the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s, he says of himself and others working the ski hill project.

"The ski industry experienced tremendous growth both in equipment development and resorts during the 1970s," Devin says in his book. "Equipment that made skiing both easier and safer brought tens of thousands of new skiers to the sport every year. It became the "in" sport both in Europe and North America." There were many individuals as well as state and local governments in Washington state wanting to develop downhill skiing, Devin says.

Left to right: Betsy, Doug, Steve, Russel and Grace Devin in a photo used for their 1977 Christmas card. Photo courtesy Doug Devin.

By 1970, he had completed and published a feasibility study for developing a family-oriented, downhill ski area at Mazama, where guests could ski and have access to a bed and a meal. There were no destination ski areas in the Northwest at the time. "Everybody went to Utah and Colorado" to downhill ski, Devin says. He and Grace, who died in 2001, moved to the Methow Valley in late 1970 so he could get an alpine ski area built.

For the next four years, he and the winter sports council promoted their plan. These were not "hard-nosed businessmen and developers," he writes. "They were people who loved the sport and simply wanted a good place to ski closer to home ... My main tool for selling development of a ski resort in the upper Methow was a 20-minute film containing scenes of skiing through glorious powder snow [on Sandy Butte] ... combined with footage of potential summer activities. I purchased a second-hand movie projector and lugged it around along with the film and copies of the feasibility study. I talked to anyone who would listen."

"In '74, we found the Aspen Company," Devin tells Grist. "We had every reason to believe there was a market [for the ski area] and it would be successful." The Aspen Skiing Company had been looking for new ventures and began working on zoning, ski-run designs and environmental assessments. The company's involvement kicked off what Devin characterizes as a "land rush" not seen since homestead days in the upper valley. As investors and speculators moved in, opponents of the ski area organized and found support among large, well-funded environmental organizations. (Aspen moved on to British Columbia to develop the Blackcomb Mountain adjacent to Whistler.)

The battle dragged on for decades, with an ever-changing cast of characters and plans, lawsuits and organizations. But on Aug. 7, 1992, the assets of the Early Winters project were sold to the R.D. Merrill company for $800,000 -- the only bid -- in a foreclosure sale at the Okanogan County courthouse. "Merrill ... had about $4.5 million plus $300,000 in equity in the project," Devin writes. "After foreclosure, all it had was the land and a Piston Bully snow groomer."

The saga continued long after that foreclosure sale. However, to this day, Devin, and some of the ski-area opponents, find a few positive remnants among the rubble left by their long and bitter fight. They agree that the Aspen Company deserves major credit for underwriting the sophisticated land-use planning that went on in the upper Methow Valley. It was way "ahead of its time" for Okanogan County, Devin says. "They spent an enormous amount of money" on experts the county never could have afforded. Devin still sits on the Mazama Advisory Committee.

Another piece of the legacy, he says, is that the lawsuit brought by environmental groups against the Forest Service for issuing a permit for the ski hill is used to teach land-use law at universities nationwide. (The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Forest Service in 1989 although legal wrangling continued.)

Asked how he feels about the Early Winters resort dream today, Devin says simply, "It was the right place but the wrong time." His biggest regret is that "It would have given the valley a major economic generator ... We're missing that now," he adds. "Everybody's just a one-man show and barely hanging in there."

Devin is retired but still helps his son with the ranch. Most of the cattle were sold in 2007, but their Mazama Livestock company raises and sells hay. And he remains an avid downhill and cross-country skier living in the shadow of Sandy Butte. Over these next few weeks, as the snowline starts dropping down the ridges, you can bet Doug Devin will put on his skis and head out to recapture that "wonderful feeling" he had as a six-year-old boy speeding down a hill on two strips of molding.

Karen West edited Mazama The Past 125 Years, the second edition of Doug Devin's book of Mazama-area history, which was published in 2008 by the Shafer Historical Museum.

11/6/2012

|

Doug Devin first started vacationing in the Methow Valley in the 1950s. Photo by Karen West

Doug Devin first started vacationing in the Methow Valley in the 1950s. Photo by Karen West

Grace and Doug Devin at their wedding dinner in the Alpina Hotel in Salzburg, Austria. Their CIA and skiing friends attended the ceremony. Grace's mother sent her a wedding dress. Photo courtesy Doug Devin.

Grace and Doug Devin at their wedding dinner in the Alpina Hotel in Salzburg, Austria. Their CIA and skiing friends attended the ceremony. Grace's mother sent her a wedding dress. Photo courtesy Doug Devin. A bumper sticker seen often in the Methow Valley when a destination ski area was proposed for Sandy Butte near Mazama. Courtesy of Doug Devin.

A bumper sticker seen often in the Methow Valley when a destination ski area was proposed for Sandy Butte near Mazama. Courtesy of Doug Devin.

Left to right: Betsy, Doug, Steve, Russel and Grace Devin in a photo used for their 1977 Christmas card. Photo courtesy Doug Devin.

Left to right: Betsy, Doug, Steve, Russel and Grace Devin in a photo used for their 1977 Christmas card. Photo courtesy Doug Devin.