home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

Pioneer Know-How  Helen Krinke outside the high-and-dry house where she’s lived since the 1948 flood washed away the home she and her late husband Bill had near Carlton. Helen Krinke outside the high-and-dry house where she’s lived since the 1948 flood washed away the home she and her late husband Bill had near Carlton.

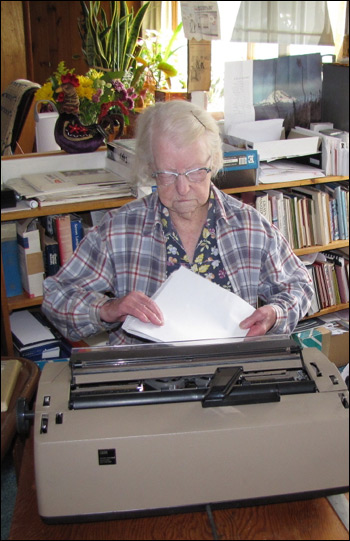

"I don’t enjoy rattlesnakes and they don’t enjoy mothballs," she explains matter-of-factly. "They seem to have a special fondness for my doorstep, which is why I look carefully before stepping outside." And if a rattler dares a stretch in the sun on her doorstep? She keeps a shovel handy. "The last few years I’ve only killed a few." Told that her name popped up as an interesting old-timer to talk with, Helen quips, "That makes me feel like the Ancient Mariner." There’s a clue in that response to her literacy but also an irony. Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner," contains the words, "Water, water, everywhere, Nor any drop to drink." What Helen and Bill Krinke didn’t know when they moved to high ground after losing their Carlton house to the 1948 flood was that the bench they chose was in the shadow of the old Alder Mine and their well water wasn’t "fit to drink." . Thus she uses it only to water the yard. All the house water comes from two buried 1,000 gallon tanks that are filled by delivery truck. The flood actually stole two Krinke homes – their original trailer house and the house they built around the trailer in Carlton. "I loved that trailer house," Helen says. Bill built it and "it was home" for 13 years as they moved from job to job. He was an ironworker for four years on the Grand Coulee Dam and on bridges across the Methow River, among other things. The couple met when he was between jobs and came to the Methow to fish. A talented carpenter, Bill built all the furniture in the present house. "The only thing we saved [from the flood] was a cedar chest and a few clothes," Helen says. Wiped out, the Krinkes moved to higher ground, strung a sheltering tarp between two pine trees and started over. They built the house where Helen lives today, covered the exterior with composition roofing for better insulation and painted it with "silver aluminum paint," which requires very little maintenance. From her cozy kitchen Helen looks out on Wolf and Little Buck mountains and Cap Wright Hill. McClure is behind her. She’s seen a few bears over the years but only spotted one cougar. Right now her challenge is the chipmunks frolicking around the wood pile that have taken a liking to her bird feeders. Helen's maternal great-grandparents Isaac and Isabell Nickell were the first white family to settle in the Methow Valley. Her father’s people, the Watsons, arrived in 1901. Grandfather James Watson bought the rights to five homesteads to form what is now the Tice Ranch. Her Uncle Jim had a ranch overlooking Moccasin Lake. Helen’s parents moved to Canada after they were married and she was born there in 1913. But her dad’s folks needed a hand with their place, so when she was 3 years old the family they returned. They later bought their own place on upper Beaver Creek. By then they had three girls. Helen, their middle daughter, graduated from Twisp High School in 1931. The homesteader’s cabin at the Shafer Historical Museum in Winthrop, where Helen once volunteered, belonged to her maternal grandparents, Isaac "Bud" Nickell and his wife Mae Lois. It shows how pioneer families started out. To this day, Helen has the skills to be as self-sustaining as her pioneering family had to be and she is outspoken on the subject. "Kids today aren’t learning the basic skills," she says, which is not a reference to reading, writing and arithmetic. "I think we depend too much on modern technology without knowledge of basic skills." We wouldn’t know how to live without electricity, eat without frequent grocery shopping or survive without a car. "If you don’t have electricity, you’re going to be lost," she warns. She has a kerosene lamp for light, a wood stove for heat and cooking, a cellar with a stock of food, and she knows how to make soap and wash on a washboard. As for transportation: "How many kids today know how to go out in the pasture, catch a horse, put a saddle on it and ride it?" Helen grew up without electricity and flush toilets. She was 13 years old before her family even had an ice house to preserve their food. Before that time food was placed in containers and put in a wash boiler ("How many kids know what that is?") that was anchored in the ditch of cold water that ran by her house. Other foods were kept in the cellar, which was cool all year. Helen's cellar is built conveniently into the hillside off her kitchen so she doesn’t have to contend with stairs. Food, much of it home-canned on her wood stove, is stored inside, including Roma tomatoes, tomato juice, apricots, peaches, pears, plums, prunes and pickled crab apples. Each jar has a neatly typed label telling the contents and date canned. She groups the jars by date so the oldest is eaten first. Helen uses her electric stove in summer and her wood stove the rest of the year. "I wouldn’t know how to live without my wood stove. I do all my canning on the wood stove," she adds, because "it’s a steady heat." Pointing her cane at the four-burner electric stove she says, "They got this wrong." Both large burners should be situated in the front to be useful for canning. A small sign on the kitchen wall hints at Helen’s sense of humor: "Middle Age is when a broad mind and a narrow waist trade places." To Helen’s way of thinking, "You’re lost if you can’t laugh at yourself. I always figure I’m the biggest joke of all." She allows that some people get mad at her for her salty remarks. "I have a habit of pointing out the basic facts," she offers by way of explanation. The day before this interview Helen mowed her lawn – with a 14-inch wide, small electric mower. It took three hours, but you’d never hear her complain; she loves working outdoors. "I’ve kinda lost track of keeping house," she says. "I can clean house when I can’t work outdoors." A widow for more than 40 years, Helen says being alone doesn’t bother her. "I just do what needs to be done." She eats two meals a day, a good breakfast and another at two or three in the afternoon, plus maybe a piece of fruit in the evening. She has a small television but finds TV boring. "I like to get the news... If I have nothing else to do I have the TV turned on but I’ll be sitting here doing needlework and not paying much attention to it...The constant advertising is enough to drive you nuts." She crochets and knits. Her latest afghan is a work in progress. She makes pot holders, some from dish cloths with padding in the center for thickness which she dresses up by crocheting around the edges.She enjoys crossword puzzles. "When I typed manuscripts I found it helps to add to your word power." She’s also critical of the computer-produced writing she reads today that "butchers the English language." She admits to no medical concerns and takes no pills although about a year ago she went to the doctor. "I had to get a health certificate to get a driver’s license, couldn’t find anything wrong with me, just empty up here" she laughs pointing to her head. Yes. She has a driver’s license and a car in the garage that she hasn’t started for about four months. But if and when she does, she’ll stick to the roads she knows. "I don’t drive much. I used to go down [to Twisp] and get the mail every day." Now, a friend brings the mail to her. She does think people used to highway driving and heavy traffic go way too fast when they drive around the valley. "They don’t know what it’s like to come around a sharp curve and find an old cow standing in the road. I’ve seen that happen too many times." She did get a new knee cap four or five years back. "I fell down out here. I was building fence and fell. My knee hit a rock." She still builds fence when required and works in her flower beds. She has given up the vegetable garden and has cut back on splitting wood. A neighbor up the road delivers, splits and stacks most of her wood, although Helen keeps assorted hatchets and axes for when she needs them.  Helen Watson Krinke's 1931 Twisp High School graduation Helen Watson Krinke's 1931 Twisp High School graduation picture. Helen grew up on a farm where everybody worked. Her parents had cows, chickens, pigs, beehives, a vegetable garden. Helen never considered herself a horsewoman but learned to drive a team and rode a horse to school. One of her horse adventures is preserved as part of Dale Dibble’s Methow Valley Pioneers: "It was about 1923 or ’24 Gladys [her older sister] and I were coming home from school at Beaver Creek. It was two or three days before Christmas and COLD! Ice was floating on the creek's surface and an ice jam was forming at the head of Bill Thurlow's ditch...where we always watered our horse. Cattle had been going in and out of the water and a smooth round mound of ice at least 11/2 or 2 feet high had rimmed the water hole.Icy watering holes aside, Helen loved school and had a perfect attendance record for her eight years at Beaver Creek. She started her own business typing book manuscripts about four years before Bill died. A writer friend from Seattle brought her the first manuscript and the business grew from there. For many years she ran a small ad in Writer’s Digest, a monthly trade magazine, that kept her work-at-home profession going. A shelf in her workroom contains dozens of books published from manuscripts she typed.  Helen in the room where she typed book manuscripts for many years. The shelves behind her contain more than three dozen of the published books. Helen in the room where she typed book manuscripts for many years. The shelves behind her contain more than three dozen of the published books. Her looks-like-new Maytag wringer washing machine also belongs to another era. She still uses it but only "when something is really dirty." She explains that she can add just the right amount of soap and keep the washer running until she knows the laundry is clean. The laundry in town is fine for lightly soiled things or a quick wash. When the Maytag is fired up, you might find Helen using homemade laundry soap. She occasionally mixes up a batch according to a recipe that contains lye, water, a little Borax and a tablespoon of sugar, among other things. The soap is poured into a box to harden and left to set for about six months. When it’s laundry time, she breaks off a block and grates it. She doesn’t own a dryer. She hangs things on the clotheslines outside her back door. So how does she grocery shop? "The girls come up maybe once a month." The girls would be two of her nieces who live in Wenatchee. "I don’t need to go shopping a lot. I’m not one of these people who gets enough for one or two meals and has to go back to the store the next day. I get enough for two or three weeks and if I don’t get to town...that’s okay, anyway. I still have a cellar... This daily shopping. I wouldn’t know how to do that... It’s a great way to spend a lot of money for very little." "The girls" also stay with Aunt Helen in her tiny house – one sleeps on the couch, the other makes a bed on the floor. "We don’t need luxury furnishings. We’re used to making do and enjoying each other." Making do and enjoying each other – perhaps that’s the secret of Helen Krinke’s long life. 7-22-2011 |