home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

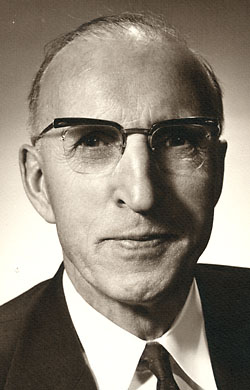

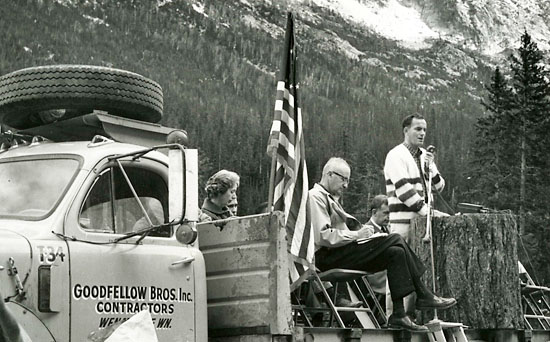

George D. Zahn, Methow orchardist and chairman of the Washington State Highway Commission, was responsible for getting funding to build the highway. Photo courtesy Eric Zahn George D. Zahn, Methow orchardist and chairman of the Washington State Highway Commission, was responsible for getting funding to build the highway. Photo courtesy Eric Zahn

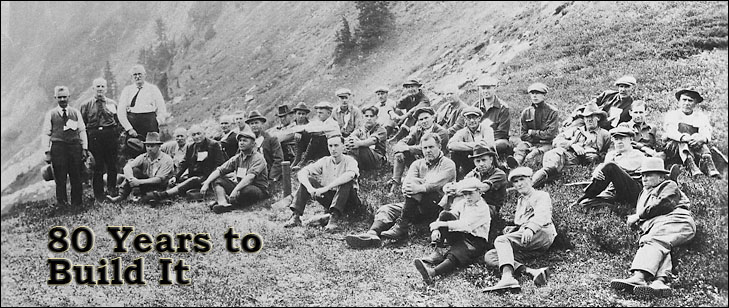

North Cascades Highway 40th Anniversary part two of three | << part one | part three >> The effort to build a white man’s passage from the Methow Valley across the North Cascades to saltwater began in 1893, when the first funds to build any highway in Washington were appropriated by the legislature to find the crossing that became the North Cascades Highway. It took until September 2, 1972, to get the job done - nearly eight decades of wasted funds, frustration and failure, countered by stubborn vision and determination, to build a highway across mountains that native people routinely were crossing 9,000 year ago. John H. McGraw was governor when the legislature first appropriated $20,000 to the Board of State Road Commissioners to scout for, and decide on, a wagon route across the North Cascades. Daniel J. Evans was the governor who nearly eight decades later cut ribbons at Winthrop and Newhalem to mark the opening of a modern paved highway. Thirteen other governors came and went before the highway was finished. The North Cascades Highway took 100 miles off the travel distance from the Methow Valley to the I-5 corridor. Few motorists who today so effortlessly cross this imposing mountain range fully appreciate what it took to get the superlatively scenic passage blasted out of a daunting wilderness where road elevations reach 5,475 feet. The desire to cross this forbidding barrier began early, according to a 1972 account by Charles Kerr in Okanogan Heritage magazine. Alexander Ross of the British North West Co. reportedly crossed the Cascades via the Twisp and Cascades passes with three Indian guides in 1816. Another notable figure who in August of 1883 took an 11-mile round-trip scouting trip along the upper Twisp River was Lt. George W. Goethals, who later supervised construction of the Panama Canal, Kerr reported. The 1893 road-building effort, a response to pleas from stockmen and miners working in Ruby and up Slate Creek, ended abruptly in 1894, according to Kerr. But in 1895 the legislature tried again with another $20,000 appropriation and a new roads commission. Three routes initially were under consideration by that road board, headed by E. M. Wilson. They were up the Cascade River and over Cascade (also called Skagit) Pass, via the North Fork of Thunder Creek, or via Slate Creek.  A Cascade Pass survey crew faced hard travel in 1921. A Cascade Pass survey crew faced hard travel in 1921.

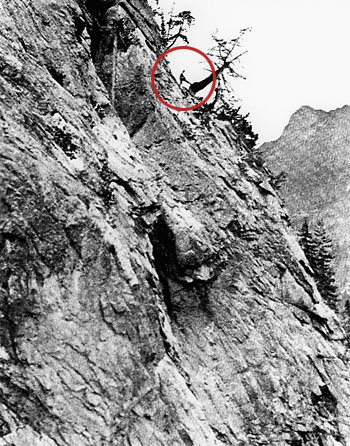

Things got off to a bad start even before this board’s first scouting expeditions could be mounted, according to its report to the governor: “The board had expected to secure the horses purchased by the former state road commission, which had been left with ex-superintendent George Y. Bowerman who had been paid for keeping them over the winter, but learned from the agent sent after them that Bowerman had taken the horses, saddles and part of the outfit with him to British Columbia instead of leaving them at Winthrop as agreed.” But the commissioners didn’t dither. They began their scouting work at the end of June in 1895. By September 11, 1895, they had made their decision: “The board found the route up the Twitsp river, over Twitsp pass, down Bridge creek, up the Stehekin river, over Cascade (or Skagit) pass and down the Cascade river the shortest and the most feasible and practicable.” In its final report, chronicled in the summer 1972 edition of Washington State Department of Transportation’s magazine, Washington Highways, the road commission expressed its modest opinion that “in no public work has the state’s funds been so well invested.” Rhapsodizing about the section between Twisp and Marblemount, the commissioners stated: “… no one not familiar with that section can have the faintest idea of its importance as a highway, or the part it will play in developing mining regions wonderfully rich but now remote, unfortunately, and furnishing a cheap method for transporting of the cattle of the Okanogan country to the desirable market on tide water… Considered from a mining standpoint no greater work could have been done anywhere. At the summit of the Cascades, where the road crosses, there are vast deposits of gold, silver and lead ores…there are excellent gold and copper regions on Bridge creek and at the head of the Twispt River.” Work commenced on a 40-foot-wide wagon road along the Cascade Pass in the spring of 1896. Laborers were paid $2 to $2.25 per day, minus 75 cents per day for room and board. Due to the expense, the road was built without a survey “except at the most critical parts of the route.” The maximum grades up the Twisp drainage were 10 percent, and a 16 percent grade carried the road over the summit without a switchback. From Twisp Pass down to Bridge Creek the grade was 12 percent, but up the Stehekin to the base of Cascade Pass summit the grade increased to 20 percent.  In 1933, Ralph Batsdorf, a survey crew member, checked out the terrain on Washington Pass. Photo courtesy Washington State Department of Highways In 1933, Ralph Batsdorf, a survey crew member, checked out the terrain on Washington Pass. Photo courtesy Washington State Department of Highways

Work stopped when the snows came, but the road optimistically was shown on maps as State Highway 1 or the Cascade Wagon Road. According to the board, an animal that previously needed a day to travel 15 miles over that terrain could now travel 30 miles in a day on the new wagon route. Trouble was, Cascade Pass was the wrong route. In 1897 floods and slides from spring runoff wiped out most of the previous year’s road work along the Cascade River. But the builders were loath to give up; they set to work repairing it. In 1899 funds were allocated for a bridge across the Methow River at Twisp and three bridges in the Bridge Creek section. That year the road commissioners reported that the road was finished and was “a good road for mountain country.” But in 1905, Washington’s first highway commissioner reported that almost all the money spent on the wagon road had been wasted. The road project was abandoned. The first attempt to cross the North Cascades ended in dismal failure. However, in the same year the legislature approved funding to build a road from Mazama to Harts Pass, which was completed in 1909. It was on the state highway system until the end of the 1940s, when the legislature removed it from the system. Still, the dream of a road over Cascade Pass didn’t die. The U.S. Forest Service, for one, would cling to that route until the 1940s. Scouting crews continued to explore routes in 1921 and in 1926. But the next serious attempt to get the project moving again didn’t begin until 1932, when a surveying expedition was launched by Ike Munson, who was to become district engineer for Washington State Highway District 2 in Wenatchee, according to Washington Highways. Munson was the person who first determined the highway should run from Twisp to Winthrop, (not to Stehekin) on the existing road, then to Mazama and up across Washington Pass, down Slate and Bridge creeks, up the Stehekin River across Cascade Pass to Marblemount. Significantly as it turned out, Munson also noted that Granite Creek would be a better route in terms of cost and alignment. World War II halted the work, but by the war’s onset a new general route over the mountains had been defined.  The highway construction crew faced steep challenges. Photo courtesy of the Shafer Historical Museum The highway construction crew faced steep challenges. Photo courtesy of the Shafer Historical Museum

In 1945 lawmakers once again allocated funds to select a highway route across the North Cascades from three possibilities. By this time decision-makers appear to have been convinced - with help from Twisp highway booster Les Holloway - that the answer lay in finding a way across Washington and Rainy passes. But years rolled by without decisive action. As Washington Highways tells the story, the decision to build the highway finally was sealed during a 1956 horseback trip led by Munson. He took the state highway commissioners on a horseback reconnaissance trip along his proposed route. Enter here Methow orchardist George D. Zahn, widely credited with being the prime mover in getting the asphalt laid across the North Cascades. He tagged along on the commissioners’ excursion into the wilderness and came out a believer. He would prove indispensable to the effort to build the highway, not only as a fervent booster who was among those insisting on the route that finally was chosen, but as the all-powerful chairman of the highway commission who got the money to get it built. A former state senator, Zahn was convinced that, as he told the Good Roads Association in a speech titled “Freeways to Freedom” on Sept. 14, 1967: “Our country’s policy is a nation on wheels.” “George Zahn was as responsible as any man ever was for getting the highway finished. He was continually able to get appropriations for the highway from various public sources. As time went on, he pretty near became the Highway Commission, and he devoted his whole life to it,” Munson told Washington Highways. Zahn died a year and one week before the highway was finished. But he did live to travel its length on Sept. 29, 1968, when Gov. Evans led hundreds of four-wheel vehicles on the historic first official, dedicatory crossing of the route, then still a rough track. Evans agrees with Munson’s assessment of Zahn. “He was a great guy. He was the one who really pushed it very hard. And he was able to do it from within the highway commission,” Evans told Grist. When Seattle City Light began building dams above Newhalem, public interest in the North Cascades area increased, according to Washington Highways. In 1953, a highway advocacy group composed of business people and politicians on both sides of the mountains, the North Cascades Highway Association, was formed. One of their major arguments for the highway was that it was needed to support logging in the timber-rich area. But that idea was scotched in 1968 when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the law creating North Cascades National Park. It finally was agreed that the eastern portion of the highway should be built past Early Winters Creek in Mazama to Washington Pass, Rainy Creek and Granite Creek. And it would become part of Highway 20, the state’s longest highway, which starts just west of Port Townsend and runs to a few hundred feet short of the Idaho border.  In 1968, Governor Daniel J. Evans led a four-wheel caravan across the rough track that became the North Cascades Highway and stopped at the summit for a dedication of the route. Photo courtesy Washington State Archives In 1968, Governor Daniel J. Evans led a four-wheel caravan across the rough track that became the North Cascades Highway and stopped at the summit for a dedication of the route. Photo courtesy Washington State Archives

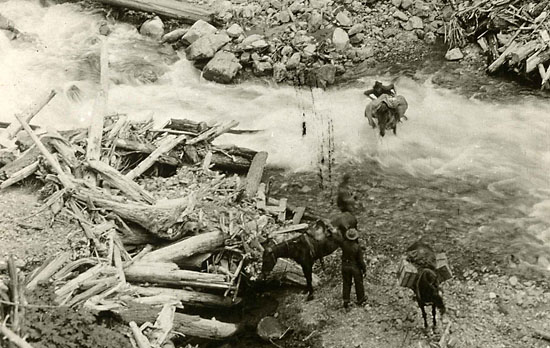

By the time construction started in 1959 to build the highway from the Seattle City Light company town of Diablo to Thunder Arm the road had gone through many names: Skagit River Road, Methow-Barron Road, Roosevelt Highway, North Cross State Highway. At first highway workers were housed in Winthrop, according to WSDOT engineer Richard Carroll, but soon they were living in a field camp near Indian Creek six miles above the mouth of Early Winters. Local highway booster Jack Wilson of Mazama was the project’s packer, and the crews he helped transport worked 10 days on and four days off.

The workers’ camp moved progressively uphill to the Cutthroat camp until they reached the summit of Washington Pass. Eventually the pack strings were replaced by helicopters that could move crews to their work locations in a couple of hours instead of a full day, according to Carroll. Fierce mosquitoes and vicious hornets had plagued scouting crews, and they plagued construction workers. Between Lone Fir and Cutthroat Creek, construction crews killed several rattlesnakes a day, Carroll recalled. Memorable mishaps included a helicopter crash on Washington Pass that forced Carroll and Munson to snowshoe out and spend the night, lightly clad, under a tree. From its 1893 beginnings, the North Cascades Highway finally was finished at an estimated cost of $33 million - early records are incomplete, according to WSDOT officials - and without loss of a single life. Between the 1959 construction start and its 1972 completion, $24 million was spent to build the highway, according to WSDOT spokesman Jeff Adamson. In marking the highway’s opening in 1972, WSDOT’s Washington Highways noted a change in the long-sought roadway’s purpose. Something new was added that hadn’t occurred to those struggling so valiantly in the late 1800s to blast a passage through the impenetrable mountains. The highway was no longer touted as a route to serve miners, though it would still bring Eastern Washington’s agricultural commodities to market. Now it also promised “economic benefit from a recreational boom which could take place when people discover the beauty to be found along the North Cascades Highway.” 8/29/2012 coming next: Life with the Highway - Cultural Changes Comments Thanks so much Karen and Solveig for these three articles. They concisely covered much of the valley's history and showed the changes from some earlier residents. I'm so glad that they still feel it is a great place to live, even after all the changes, and I thank them for still welcoming us to their valley. Dennis O'Callaghan Winthrop Once again I'm impressed with the thoughtful and in depth look at subjects that affect us here in the Methow. Thank You Grist! Don Ashford Rockview Dance Hall

|