home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

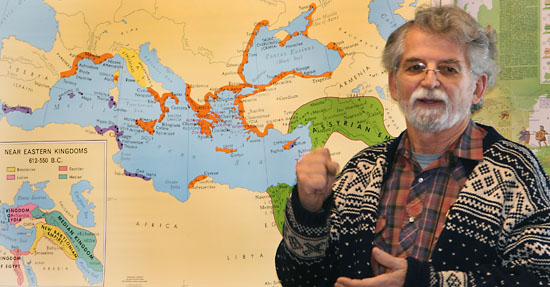

Killer Historian  Bill has had a love of maps since he was six years old. - Photo by Solveig Torvik Bill has had a love of maps since he was six years old. - Photo by Solveig Torvik

Just as they have for the last 17 years, history buffs gather on these wintery mornings to be guided by Bill Hottell through another chapter in the story of humanity. This year it’s England, and some 65 people, from home-schooled elementary students to 90-somethings, fill the classroom at the United Methodist Church. Hottell, 73, comes to the front of the class with remarkable credentials. True, he taught history and Spanish (he’s also fluent in ancient Greek and Latin and gets by in Italian and French) at Liberty Bell High School from 1973 until 1989, and he led its giant-killer Knowledge Bowl teams to impressive victories. But this genial, mild-mannered teacher brings an uncommon range of personal experience to the classroom. For one thing, he’s trained as a killer. “I learned to kill in 95 different ways,” he says matter-of-factly of his time at the U.S. Marine Corps boot camp at Parris Island, S.C. He describes that training as extreme and phenomenally demanding. “I loved it,” he says, and in 1966 he broke a base record by doing 150 pushups. “I was clearly the most sadistic person down there,” he jokes. Improbably, this was after he’d spent six years in rigorous training to become a Jesuit priest. Though trained killers and Jesuit priests may seem to have precious little in common, Hottell says they share one fundamental trait: devotion to extreme discipline. And, he admits, he thrives on it. The Jesuits pushed him to his intellectual limits, he says, and the Marine Corps pushed him to his physical limits. He still marvels at the skill of his drill sergeant, “a master teacher who had a genius for turning mediocre, pathetic American boys into killing machines.” Hottell says he left the Jesuits when he realized he wanted to be married one day. “There was a bit of shame involved,” he says. “I felt a bit of a failure.” He volunteered for the marines while doing graduate studies in history and political science at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., knowing he likely would soon be drafted. “I think I’ve always liked extremes,” he offers by way of explanation for adapting so readily to both the life of a priest and that of a soldier. He was accepted for officer training school at Quantico, Va, and was on his way to becoming a second lieutenant bound for combat in Vietnam. But he lasted only 10 days. He sent a postcard to his then-girlfriend Diana reporting the shockingly obscene language drill sergeants used to train their charges. Mail was censored, and he was summarily demoted and shipped off to basic training at Parris Island. Given the high mortality rates of second lieutenants in that war, Hottell says his poor judgment probably saved his life; in any case, it meant one less year of military service. Hottell and his wife Diana met in the nation’s capital while he was in graduate school - she heard him playing the piano one day as she walked by his apartment. They lived three doors, and worlds, apart. Her father was a prominent government official; her mother’s lineage included General Robert E. Lee of Virginia. Their home was the scene of dinners attended by Washington’s political elite, some of whom were among the guests when Bill and Diana married in Washington’s historic St. Matthew’s Cathedral, where funeral mass was celebrated for President John F. Kennedy. Hottell had been supporting himself by playing the piano in a “speakeasy” three blocks from the White House and supplementing his meager diet with Alpo dog food. While in graduate school, he’d spent three days in jail after being arrested by a railroad detective who caught him riding in a boxcar en route to Appalachia. “I’ve always had a fascination with railroad hoboes -`The Kings of the Road,’” as he calls them.  Bill Hottell at about two years of age with his father, Bill Sr., and dog at their farm near Curlew in Ferry County. - Photo courtesy Bill Hottell Bill Hottell at about two years of age with his father, Bill Sr., and dog at their farm near Curlew in Ferry County. - Photo courtesy Bill Hottell

A descendant of pioneers who came West from Missouri by covered wagon during the Nez Perce War, Hottell lived for the first 12 years of his life on a hardscrabble farm in Deer Creek near Curlew in Ferry County, then moved to Spokane. There he attended Gonzaga Preparatory School and, in a ”totally transformative” experience, fell in love with learning. “That’s when I discovered the life of the mind, the world of ideas. I knew that’s what I wanted to do.” His father had taught him practical skills such as carpentry and assigned him the task of painting a house by himself when Hottell was only nine. “Dad was very abrasive. He didn’t know how to work well with others,” he says. “I’ve deliberately avoided doing all those practical things,” he chuckles. His mother was a school teacher who instilled in him a love of the maps she brought home from school, and he was spreading them on the floor and poring over them from the time he was six years old. He learned to play the piano, and was tutored by Spokane’s noted band leader, Norm Thue. At age 18, Hottell began four years of study for the priesthood in a Jesuit novitiate on a mountaintop in Sheridan, Oregon, then spent two more years at Mount St. Michael’s seminary near Spokane. “I loved it. It was Spartan living.” At the novitiate, there was no talking, except for 30 minutes after dinner. “It was like going back in a time machine 1,000 years ago,” he says fondly of that life. The Jesuit curriculum was daunting. Courses were taught in four languages – Latin, Greek, French and English. Among the subjects were history of literature; drama and rhetoric. The Greek lyric poets, philosophers and dramatists; Shakespeare and Moliere; Edmund Burke and Daniel Webster, were just a few whose works were to be mastered. “The examinations were brutal,” Hottell says, and the oral exams were conducted in Latin. “The Jesuits are the masters of education,” he adds, and their demand for excellence was “very gratifying.” Their tutelage shaped his approach to teaching. “I can’t stand mediocrity – wasting time and talent,” he says. “That permeates all the courses I’ve taught. I just will not tolerate anyone coming to school without having done the homework, or taking it seriously.” After he completed his two years of military service in California, the Hottells set off on a sometimes hair-raising, 19-month around-the-world adventure in a Volkswagen van. They began with nine months in Europe, he visiting for the first time the historic sites that later would become familiar to valley residents on tours he led; he also guided tours for the Smithsonian Institution and the Chicago-based organization Art Encounter. After Europe, the Hottells shipped their van to South Africa, spending three months near the Cape. As they drove on toward Nairobi, they realized they’d have to illegally sell their van: too many roads had vanished when the British did. It proved far easier than expected. Just as they arrived in Nairobi and pulled into a parking place, a man approached them and said: “You wouldn’t be interested in selling your van, would you?” Turned out he was an artist from Spokane who needed the van for his work. In South Africa, a highly venomous, tree-dwelling green mamba snake they didn’t know was poisonous tried to land on Diana, alerting them to the need to travel with snake-bite antidote. They flew to Uganda, then to southern Sudan, where they boarded an ancient, over-loaded riverboat to sail down the Nile. En route, a child fell overboard and vanished. The Nairobi bureau chief for Time magazine was the only other white person on board. Among the rest were 300 soldiers. “We were going through a war, which came as a surprise to the two of us,” Hottell says. Then, when they got on the train to Khartoum, they discovered a coup was taking place there. They stayed in a hostel, roaming the city, and every day stopped by the Grand Hotel, where the Time bureau chief was preparing exclusive dispatches on the coup, and filled him in on tidbits of information they’d observed around town. They trekked around in the Kalahari Desert, climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro, sailed the Nile in Egypt on a felucca and biked around the ancient ruins of Karnak and Luxor, crossed the Khyber Pass and spent two weeks on a houseboat on a lake in India. They visited Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Cambodia and Burma. No one was going to Burma in those days, according to Hottell, so they ended up in first class as the only passengers on a large jet with seven cabin attendants. After visiting the ruins of Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, they flew on to Saigon on the day that Ho Chi Minh died. On approach they had a bird’s-eye view of fields of slime-filled craters caused by American bombing. But that was to be all of Vietnam they would see - on that trip. They were immediately expelled from the country, ordered to leave the same afternoon. They had visited all the wrong, Communist-leaning countries, Hottell explains. “We had to take the next flight to Australia.” So they hitchhiked across Australia from Darwin to Sydney - a distance of more than 2,500 miles - where they stayed six weeks before sailing home. Booker T. Washington High School in New Orleans, a penitentiary-like campus with 2,100 black students, in 1969 was Hottell’s first teaching assignment. It was the last year such racially segregated schools were legal. “It was baptism by fire,” he recalls. “I ended up teaching Black history.” For Black History Week, he and Diana played music for the students and explained the African history of the banjo, an instrument she plays. White people rarely were seen at the school, he says, and the Hottells were treated as novelties. When singer Mahalia Jackson, a graduate of the school, came back to sing for the students, Hottell adds, “I just wept.”  Bill Hottell recently had to pare down his collection of history books when he moved to a new house in Twisp. He says his collection had been the largest in the county. - Photo by Solveig Torvik Bill Hottell recently had to pare down his collection of history books when he moved to a new house in Twisp. He says his collection had been the largest in the county. - Photo by Solveig TorvikNext stop was a teaching job in Ketchikan, Alaska, where the sun shone only six days during the entire school year and where one-third of the student body was Tlingit. From Alaska, they drove another Volkswagen van to the tip of the South American continent at Tierra del Fuego in Chile. After that 13-month journey, they were ready to settle down. As Hottell tells it, he was drawn back to this region because he felt at home here. But as they were driving up from Wenatchee on a scouting trip, it was Diana who studied the map and said, “Twisp. That’s where I want to live.” She’d never seen it, and he had only been here once before in 1963, when he climbed Silver Star Mountain. “It was so breathtakingly beautiful it stayed in my mind,” he says. Since the first recorded ascent of Silver Star in 1932, it had remained so untouched that even three decades later, his group was only the fifth to have climbed it, he says. Two months before the North Cascades Highway opened for business in 1972, the Hottells bought their place up the Twisp River. They lived there until a few weeks ago, when they moved into a new home in downtown Twisp. Shortly after they arrived in the valley, they began playing music at the Antlers’ Tavern in Twisp. They performed there every week for the next 17 years, and the Hottell Ragtime Jazz Band still draws enthusiastic crowds whenever it performs. Hottell embarked on the teaching career at Liberty Bell High School that made him such a memorable figure in the lives of so many people in the valley. A highlight of his teaching career was the High School Bowl, today’s Knowledge Bowl. Originally it was televised, and Hottell was the team coach. And, no surprise, he admits to drilling the students mercilessly. “For me it was so exhilarating to watch those kids compete,” he says. A string of victories for the tiny school soon galvanized the kind of community support for Liberty Bell’s scholars that had been reserved for its sports teams, he says. One by one Liberty Bell knocked off teams from bigger schools – Brewster, the long-standing sports adversary; Walla Walla; Baker, Ore., and Seattle’s Garfield and Franklin high schools among them. A particularly intimidating foe was the team from the high school in Moscow, Idaho, which was peppered with professors’ kids. “They had not lost for four years,” Hottell recalls. “Everyone was depressed. They were giants. And we beat them.” By anyone’s definition, his amounts to a life filled with extraordinarily enriching experiences. Hottell sums it all up simply: “Really fortunate things keep happening to us.”2/1/2012 read Bill Hottell's travelogues and other past postings in the archive >> Comments Terrific article, Solveig, about a great guy. Very informative. For example, I'd always wondered if Bill had sprung from the womb with a full white beard. Now I know that he didn't. Anyone who, for fun, reads ancient Greek literature in the original Greek you know must be interesting. What makes Bill's history classes so good is how strongly invested he is, personally, in the material. I remember a few years ago, in his class on ancient Greece, a classmate asked him what would have happened if the Greeks had lost the battle of Marathon. Bill got so choked up, in front of the class, thinking about the possibility that the Golden Age of Greece might never have existed, that it was a full minute before he could regain his composure. with best regards, Kurt Snover Kurt Snover Winthrop, WA

|