home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

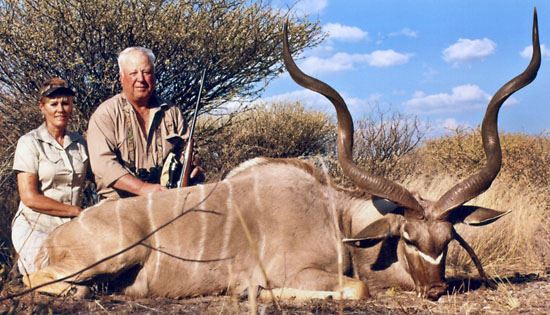

Hank Konrad poses with the male lion and warthog exhibit that greets shoppers at his supermarket in Twisp. Photo by Karen West Hank Konrad poses with the male lion and warthog exhibit that greets shoppers at his supermarket in Twisp. Photo by Karen West7 Tons, One Shot It’s not every day that you can walk into a local supermarket and find an African lion attacking a warthog right there by the checkout counters – unless you’re shopping at Hank’s Harvest Foods in Twisp. The lion and warthog are among dozens of trophy animals from Africa, Canada and a smattering of other countries on display at the store, most of them sharing space with an assortment of merchandise stacked above the freezer cases. “I ran out of room at home so I brought some of them down here for the kids to see,” explains Hank Konrad, store owner and passionate hunter. Each animal has a story. For example, that male lion from Zambia that’s about to dine on the warthog was probably six or seven years old when he died. He had 19 females in his pride and is believed to have fathered three cycles of cubs, Konrad said. But after losing his pride and territory to another male, he was found wandering hungry and alone. He was so thin his ribs and spine stuck out, according to Jackson Konrad, Hank’s son, who was with him on the trip.  Judy and Hank Konrad pose with a greater kudu bull, a woodland antelope, taken for meat in Botswana last year while they were hunting in the Kalahari. Photo courtesy of Hank Konrad Judy and Hank Konrad pose with a greater kudu bull, a woodland antelope, taken for meat in Botswana last year while they were hunting in the Kalahari. Photo courtesy of Hank Konrad“I tracked him for 12 days because I didn’t want to bait him,” Hank said. Finally, the lion came into the open. “He stopped and looked back.” It was the only moment Konrad had to take a shot and he didn’t hesitate. The warthog is from Zimbabwe. “I shot him [on a different trip] so we could have dinner,” Konrad explained. The warthog skull that’s part of the exhibit is from the animal on display; the lion skull is not. Both animals were restored to life-like prime by a taxidermist friend who lives outside Missoula, Mont. He’s worked on all the African animals for Konrad, who said he prefers poses and facial expressions that are as natural as possible – no snarls and added drama. He doesn’t discuss the business side of his passion, but Konrad said, “I’m not taking anything out of the store [to pay] for hunting.”  A male Himalayan Tahr, a wild goat with a lion-like mane, watches over grocery shoppers. Konrad shot it in New Zealand, where Tahr goats are hunted for meat. Photo by Karen West A male Himalayan Tahr, a wild goat with a lion-like mane, watches over grocery shoppers. Konrad shot it in New Zealand, where Tahr goats are hunted for meat. Photo by Karen WestAnd while he’s hunted many kinds of animals, Konrad said, “I’m not a scorekeeper kind of guy.” In fact, after about two dozen trips to Africa, elephants are the only animal he hunts there – unless “somebody wants something to eat.” Why? “Because it’s the biggest challenge… I’m not a killer. I’m a hunter.” It takes absolute focus, he explained, to stand face-to-face with a charging bull elephant, knowing he wants to kill you and you want to drop him with a single shot to the brain so he dies instantly. Konrad said he’s never missed that shot. His elephant gun holds two .500 Nitro cartridges and the tracker who accompanies him also has a rifle – just in case. One year he shot a bull that weighed 14,000 pounds. It was estimated to be about 70 years old, the upper end of an elephant’s lifespan. He only had one molar left in his mouth and couldn’t chew food properly, said Konrad, who started hunting as a child. “I was born in the woods, outside Grangeville,” Idaho, into a family that raised some cattle, ran a small logging operation and worked as outfitters during elk hunting season, he said. His mother was a quarter Nez Perce and his dad a quarter Crow. When he was in high school, Konrad recalled, “I used to get on the school bus every Friday with my rifle and my pack and nobody blinked an eye.” After school, he went to a ranch for target practice. “All the kids with pickups in the [school] parking lot had rifles in the rack,” he added. “Nobody shot anybody.” He is a life member of Safari Club International, the Wild Sheep Foundation, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, the Mule Deer Foundation and the National Rifle Association. His three kids were trained in firearm safety and his six grandchildren will be, too. He said he opposes gun control. He also said the United States government has gotten too big and is weakening the country. “We need to be self reliant again,” Konrad said. “We’ve taught our children that somebody else is responsible for everything. But that’s not the way it is.” Self-reliance, by his definition, means taking care of your own – your kids, parents and the people in your own community -- and not expecting the government to do it. Konrad is legendary for quietly extending a generous helping hand in the community. “There’s nothing I won’t do for a working man but there’s nothing I’ll do for a man who won’t,” he said.  Hank Konrad displays an 84-pound elephant tusk, one of the pair he has from his 2012 hunt in Botswana. Since the mid-1980s all elephant tusks being shipped from Africa are assigned a serial number to help track the ivory. Hunters must have permits and document their hunts with photographs. Konrad donates the hide and all meat to local villagers. Photo by Karen West Hank Konrad displays an 84-pound elephant tusk, one of the pair he has from his 2012 hunt in Botswana. Since the mid-1980s all elephant tusks being shipped from Africa are assigned a serial number to help track the ivory. Hunters must have permits and document their hunts with photographs. Konrad donates the hide and all meat to local villagers. Photo by Karen WestHard work has been a hallmark of his life. He said his great-grandmother, Eva Cash, long ago told him: “All good things come to he who waits as long as he works like hell while he’s waiting.” In 1975, Konrad moved to Twisp with his wife, Judy, a native of Lewiston, Idaho, and his brother and his wife. They bought the ‘Buckingham Palace’ grocery store, which was located where the Confluence Gallery is today. “I worked 15 hours a day, seven days a week,” Konrad said. “I took a half-day off when Stephanie was born.” Stephanie is the eldest of the Konrad’s three children. She’s living in Wyoming, although her son works at the store. So do the Konrad’s other two children – daughter, Carlan, and son, Jackson, who runs the meat shop. Judy Konrad works in the office. Hank’s Harvest Foods employs 54 people, making it one of the largest employers in the valley. Over the years, Konrad has had several businesses in addition to the grocery store including an excavating company and a well-digging business. He’s also invested in real estate. The family lives on a 1,000 acre ranch put together over the years up Finley Canyon, where the kids can learn about life by roaming the hills, hunting, fishing in the lake and riding their ATVs where grandpa designates so they don’t “tear up the land.” And you can bet they know the stories of the animals in his trophy room. Konrad said he likes to travel “but I want to go into the bush and meet the real people.” Judy accompanies him and does some hunting, although she also travels with a group of friends to tourist sites and countries he doesn’t care about. His first trip outside the United States was with the U.S. Army to Vietnam, where he spent part of three different years. There he befriended an “old Frenchman” who talked to him about the place. His passion for Africa was ignited years later when he saw some films about hunting there. It looked challenging. But the appeal has many facets – the expanses of land, the quiet, “tracking in the African bush and meeting the indigenous people who live out there” for whom hunting “is a way of life.”  About two dozen white tail and mule deer trophies are on display above the freezer cases. Photo by Karen West About two dozen white tail and mule deer trophies are on display above the freezer cases. Photo by Karen WestKonrad said he hunts on government lands that are equivalent to our Forest Service lands, where the herds are managed and park rangers set the quotas on the number of permits issued. The Safari Club promotes hunting and conservation by taking care of the animal populations, he said. It also sponsors anti-poaching teams. “Africa, right now, would pretty much be without animals if it wasn’t for Safari Club International.” “Hunting is a positive thing for all animals because it gives them a value and without it, they’re gone,” Konrad said. “The trophy fee for an elephant can feed a village for a year, plus they get the meat.” If he gets an elephant permit this year, Hank and Judy Konrad will make what he expects to be their last elephant-hunting trip to Botswana in August. The permits for where he wants to go may be auctioned off to some very wealthy bidders, he said, which could change his plan. That would be a bittersweet decision for a man who has tracked elephants up to 60 miles through the African bush that so strongly calls to him. 3/4/2013 Comments

|