home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

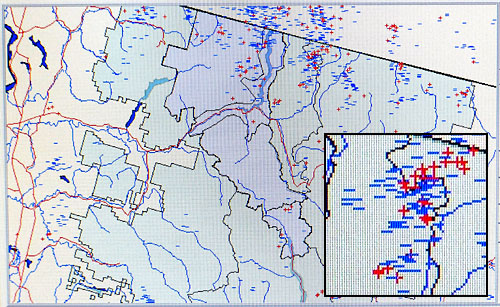

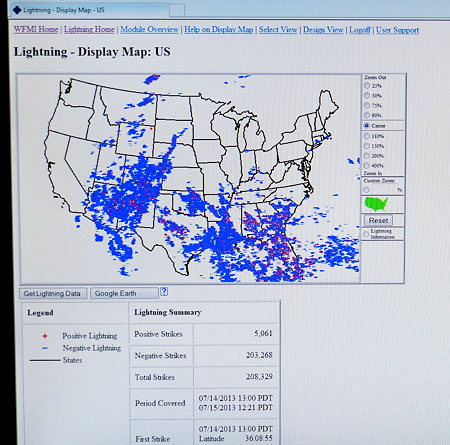

Dee Townsend’s computer screen in Winthrop shows lightning strikes in North Central Washington and southern British Columbia during recent thunderstorms. The lightning display system depicts both positive and negative lightning (shown in inset). Statistically, positive lightning bolts start more fires. Strikes can also be displayed as a table of time and location (latitude and longitude). Photo by Sheela McLean Dee Townsend’s computer screen in Winthrop shows lightning strikes in North Central Washington and southern British Columbia during recent thunderstorms. The lightning display system depicts both positive and negative lightning (shown in inset). Statistically, positive lightning bolts start more fires. Strikes can also be displayed as a table of time and location (latitude and longitude). Photo by Sheela McLeanFlash Tracker Wildfire detection in the Methow Valley runs the gamut of technological sophistication from human eyes stationed in a wooden lookout tower to highly sophisticated and centralized lightning detection systems gathering data nationally, allowing firefighters and weather experts to see where lightning has struck almost real time. Dee Townsend is the fire management officer for the North Cascades National Park and for the Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area, but she lives in Winthrop and most often works from her office in the Chewuch Professional Building in town---unless she’s off fighting fire somewhere. Working remotely, she relies on a lightning detection system to help forecast what firefighting resources might be needed and where. Fire specialists at the Methow Valley Ranger District are also plugged in by computer to lightning detection systems and also use the information to prepare for and manage wildfires. As this story was being written, Ann Sprague and Jose Valdovinos of the Methow Valley Ranger District were working in Wenatchee at the fire dispatch center, and were keeping an eye on lightning maps on their computers.  From the hills west of the Chewuch River, lightning forks into the Methow Valley near Winthrop during a storm in the past. Photo by Curtis Edwards From the hills west of the Chewuch River, lightning forks into the Methow Valley near Winthrop during a storm in the past. Photo by Curtis Edwards"More than 18,000 lightning strikes were detected…througout Washington Friday night and on Saturday," according to a Forest Service news release. By 6:30 p.m. on Saturday (August 10) "more than 60 fires had been reported to the Central Wahsington Interagency Communications Center in East Wenatchee and more were expected." Lightning detection helps Townsend decide if a reconnaissance flight is needed, and where it should fly. It helps firefighters know where ‘sleeper’ fires might be expected: sleepers are fires that lay low, too small to see until conditions change and the fire starts moving and putting out more smoke. The system helps Townsend keep a constant eye on remote park areas where finding fires early is especially important—such near the international border with Canada, along the Highway 20 corridor, with all its travelers and around Stehekin, which is a populated area surrounded by mountainous parklands and accessible only by air, trail, or boat. From her computer, Townsend can pull up maps that show lightning across the whole United States and lower Canada, or just the west, a smaller piece of the west, or just ‘her’ parks—she can choose boundaries. The maps usually update every 15 minutes, but Townsend can crank it up until it is refreshing once every minute. Townsend can also pull up tables that detail every strike portrayed on the map, giving the strike’s latitude and longitude, and whether it was positive or negative. Statistically, positive ground strikes start more fires than negative ground strikes.  The display map gives Townsend an idea of lightning activity across the nation, which helps predict how much demand there will be for firefighting resources. Photo by Sheela McLean The display map gives Townsend an idea of lightning activity across the nation, which helps predict how much demand there will be for firefighting resources. Photo by Sheela McLeanThe lightning is not detected from satellites, which might be a person’s first guess. Across the country, 114 remote ground-based lightning sensors feed the National Lightning Data Network that is used by the National Weather Service in Seattle, according to Kirby Cook of the Weather Service office there. According to a NASA website, “sensors send raw data via satellite to the Network Control Center in Tucson, Arizona. Sensors instantly detect the electromagnetic signals created when lightning strikes the Earth's surface. Within seconds, the NCC's central analyzers process information on location, time, polarity, and amplitude of each stroke.” The network has three sensors in Washington, according to Kirby Cook of the National Weather Service is Seattle: one not far from Port Angeles, one in north central Washington east of the Methow Valley and one near Walla Walla. Oregon also has three sensors. The sensors can tell the direction of the electromagnetic signals, according to John Livingston of the National Weather Service in Spokane. If three stations detect the signal, they can triangulate the exact position of the strike. The Bureau of Land Management started the lightning detection system in the west in the 1980’s Livingston said. It has since moved into private hands: federal agencies purchase the data from private companies. The National Lightning Data Network, the U.S. Precision Lightning Network and the Earth Networks Total Lightning Network are lightning detection organizations found by a web search. The detection system is supported nationally by the Bureau of Land Management and by the National Interagency Fire Center. It is password protected, and not available to the general public. Viasala, Inc., which runs the National Lightning Data Network, puts out free lightning information to the public on their website. The free information is very general and has a 20 minute delay, but it does give the viewer an idea of where lighting is landing in the United States. 8/11/2013 Comments

|