Budget cuts are pushing the Methow Valley Ranger District closer to ending a storied and romantic tradition here: paying people to perch on the top of mountains in high lookouts, watching over the back country for fires and communicating for crews deep in the mountains.

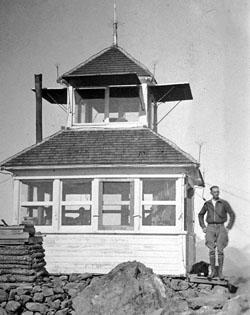

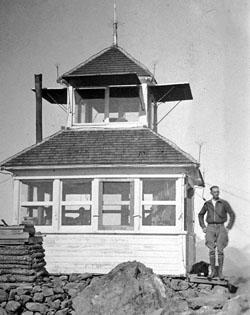

Goat Peak Lookout in 1923. The firefinder is in the cupola. Photo by Ferd Haase from the Shirley Haase Collection. (click to enlarge)

“Funding is down for the forest in the area of fire prevention,” said Methow Valley District Ranger Mike Liu. Initially, Liu thought there would be no money for staffed lookouts at all, but with some district-level budget shifts, he believes ”we can at least staff the Goat Peak Lookout.”

Liu said that the district will likely still have a 15-person hand crew and two engines for firefighting stationed in the valley. That’s the same level as last season.

The ranger district plans to keep Goat Peak open because so many summer visitors climb the mountain above Mazama to visit the lookout, which has views over the deep backcountry of the Pasayten Wilderness. Besides a public host and a well-experienced pair of fire-finding eyes, the lookout also provides a backup safety communication link. If other links aren’t working, crews “often can still hit Goat Peak” by radio, said Liu.

“We may consider opening the Leecher Lookout depending on volunteer interest,” added Liu.

Winthrop resident and town council member Mort Banasky was paid to spend last summer in Leecher Mountain Lookout, which stands above the Twisp River drainage. She has staffed Methow Valley lookouts for almost three decades, and is known for her time on First Butte above the Chewuch River valley.

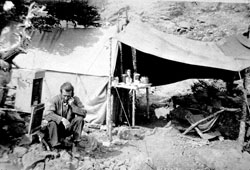

Home for an early Forest Service employee on Lookout Mountain. Communication was by telephone. (click to enlarge)

Liu said both Leecher and Goat Peak have recently been maintained, but since then, newer requirements have come out. Liu said it will cost to review and make sure a lookout meets the newest propane and lighting protection standards. “We hope to have very little to do,” on Goat Peak and, possibly - if the right volunteer shows up - Leecher Mountain, he said.

Nation-wide the Forest Service is on alert about propane systems in old lookouts because of a recent close call: an employee was poisoned with propane, but survived by spending the night with the windows and doors open though temperatures were in the 20s.

Bill Austin, known as “Lightning Bill”, staffed Goat Peak Lookout last year, as he has been for 17 seasons. He said in 1995 Goat Peak got about 600 lookout visitors, but estimates that has built to somewhere between 1,500 and 2,000 each season.

Austin’s first lookout job was on Chelan Butte in 1978. “I spotted a fire my first day,” he said. Since then he has spent 36 seasons as a firefighter, helitack crew member, and lookout. His nickname came from the fact that “I love lighting….and I respect it.” Austin grew up in the Methow Valley. His father, Frank Austin, had been a lookout before him.

“I’m praying I got a job,” this season on Goat Peak, Lightning Bill said.

Fire detection and fire-fighting technology has moved a long way since the beginning. In August 1911 the Okanogan Independent newspaper reported: “The trail from Sweat Creek Ranger Station to the lookout on Buck’s Peak has been swamped and cleared. In the Buck Mountain district 35 shovels, ten axes and nine mattocks, all with red handles, have been secured to be used in case of fire. It is thought that the red handled tools will not catch on fire or be lost so easily as the unpainted ones were.”

A log cabin with a pole to climb like a ship’s mast to check for fires, served as the Buck Mountain Lookout in 1923. (click to enlarge)

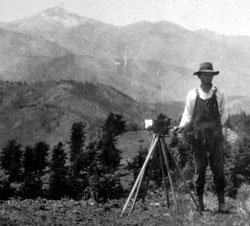

In August 1912, the Independent reported that “the officials of the Okanogan national forest are feeling highly elated over the results accomplished with the heliographs that were introduced as a means of communication between the lookout stations in the forest this year. It has been proven beyond a doubt that they are practical instruments where inadvisable to place a telephone. . . Four out of the six lookout stations in the Okanogan Forest are equipped with telephones, all of which have been temporarily connected with some trunk line by use of insulated wire. The insulated wire has not proven as satisfactory as was hoped, however. Where cattle or other animals are being grazed to any extent it is practically useless to lay the wire on the ground as it breaks when the cattle become entangled in it. It has likewise been found impractical to lay it in a trench with soil over it as the insulation is defective enough to allow the dampness to cause a short circuit. The most satisfactory way in which it has been tried is to lay it over the limbs of trees or anything to keep it out of danger of stock.”

Lookout and Leecher mountains had heliographs, which depended on sunlight to send bright flashes in Morse code. Aeneas and Funk mountains had acetylene gas signals, which worked in the night. In 1912, they all had telephones lines also—such as they were in those times.

1913 and 1914 saw crews building log structures sporting cupolas with windows on all four sides. Lookouts could stay in cabins instead of tents.

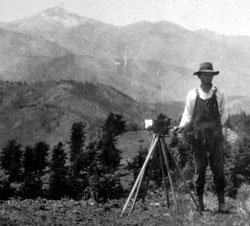

Heliographs, like this one on Lookout Mountain, used sunlight to flash Morse code messages between lookouts and stations. They quickly gave way to telephones and then radios. (click to enlarge)

The heliograph and acetylene gas lights fizzled in favor of the telephone, and the telephone eventually gave way to the radio. Lookouts increased.

By 1921, the Methow Valley Journal reported that “Gwen Creveling will be the fire lookout on North Twenty Mile this summer. Miss Creveling is one of the very few women in the United States to serve in these lonely positions.” Gwennie Creveling’s married name was Gwennie Yockey; she was a seasoned lookout at the time of the Journal’s report.

The 1930’s were the peak (so to speak) of lookouts in this area. By then radios were the main communication link. In 1931, the Methow Valley news reported: “Radio Working Fine: The Chelan National Forest has been designated as the first in the entire country to try out this latest method of forest communication. Twelve semi-portable sets have been placed on as many lookouts and about 65 small fourteen pound “portables” are scattered all over the forest in the hands of guards.”

Life as a lookout was not always serene. The Methow Valley Journal reported in September 1932 that “lightning Friday entered into almost too familiar terms with Roy Paul, lookout on Slate Peak. Roy miraculously escaped injury when his cabin was visited by a bolt which played havoc with the electrical equipment and furnishings. Roy had returned from a fire sighted earlier in the day. He had been caught in a heavy rain storm and was changing his clothes while the lightning rang the telephone bells, played hide-and-seek among the arresters, and amused itself by flaying the crags near the cabin. Suddenly there was a blinding flash and a deafening explosion. When the smoke cleared Roy found all fuses and arresters burned out, two pairs of blankets and some clothing consumed, and a cross-cut saw ruined.”

In the following decades, remote weather prediction and lightning detection improved, as did aircraft and firefighting techniques, not to mention communication technology. The need for people stationed all season in high places diminished. Most lookout structures were abandoned or destroyed by the 1950’s to mid-1960’s.

This summer, 2012, around a century after the beginnings, it’s likely that ‘Lightning Bill’ will be this area’s only lookout, perched on Goat Peak above the upper Methow Valley. |