home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

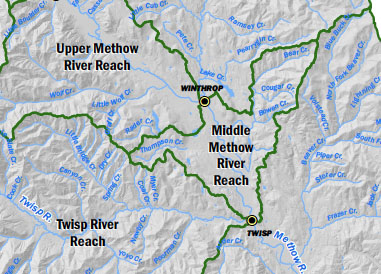

Water in the Bank? The Methow Watershed Council’s effort to obtain legislative authorization to become a water rights bank and manage the valley’s water has met with a roadblock from the Okanogan County Commissioners. The council’s proposal would allow it to bank water rights deposited by willing donors. It also would have authority to dam and store water and move unused water downstream from the Early Winters Reach, the only one of the valley’s seven reaches that has excess water. This would free up water for use by commercial entities and by the towns of Winthrop and water-strapped Twisp, according to council chair Greg Knott. Council officials say they are trying to avoid having the state Department of Ecology impose a building moratorium in the Methow Valley if and when Ecology decides that the controversial in-stream flow reservation in the Methow River and its tributaries has fallen below the legally required 2 cubic feet per second. It was imposed by lawmakers in 1976 to preserve water for fish.  Greg Knott, chair of the Methow Watershed Council. Photo by Solveig Torvik Greg Knott, chair of the Methow Watershed Council. Photo by Solveig TorvikThe council has argued, so far unsuccessfully, that the county must make water availability the deciding factor when approving development. More than 20,000 existing undeveloped parcels approved for development by the county in the lower valley will be unable to legally obtain water if all the parcels are approved by the county are developed, according to the council’s projections. The council long has been warning that the Methow is facing a future of big trouble over water. When all the valley’s existing water claims and water rights are added up, they amount to 10 to 11 times more water than the Methow basin contains, according to Knott, who owns Van Hees Environmental of Twisp, a consulting service. He told Methow Grist that most of what are assumed to be water rights in the Methow are really unproven water claims; water claims don’t become legally proven water rights until they are adjudicated and approved by a Superior Court judge. Only Libby, Beaver, Bear and Wolf creeks, Gold and Black canyons and Davis Lake have been adjudicated. If the county does not sign off on the watershed council’s plan to establish local control over water management, Ecology will dictate how water in the Methow will be apportioned should the agency determine that the 2cfs threshold has been crossed, watershed council officials warned at an Oct. 8 meeting with the county commissioners.  Okanogan County Commissioner Ray Campbell. Photo by Solveig Torvik Okanogan County Commissioner Ray Campbell. Photo by Solveig TorvikThe council has been unable to get a response from Ecology as to how it will define and decide when the 2cfs limit has been violated, Knott told the commissioners. The only place Ecology reads Methow River flow meters is in Pateros, he said. However, the council’s plea for support for its plan to set up local water management control to avoid an eventual crisis failed to persuade the commissioners. The 2cfs “is paper water,” said commissioner Ray Campbell of Carlton, a former member of the watershed council. “It’s a regulatory tool they put on citizens.” He argued that the 2cfs is a number pulled “out of thin air” and said the valley has more water available than Ecology gives it credit for having. Knott said he agreed with Campbell’s characterization of the unreliability of the 2cfs determination but stressed to the commissioners that the Methow nonetheless is legally bound by its constraints. The solution, he argued, is to set up a local water management authority before problems worsen rather than rely on Ecology to solve the valley’s water problems after the 2cfs is breached. Knott told the commissioners that the new entity would not be yet another regulatory body but instead serve in an advisory capacity to the county, which would continue to be represented on the new entity just as it is on the present council. The watershed council was formed in 1999 at Ecology’s behest to prepare a plan for managing the valley’s water. The Methow Watershed Plan is completed and was accepted by the county commissioners in 2005; in 2009 the commissioners approved an implementation plan which included a call for a revision of the so-called Methow Rule that specifies the 2cfs limit.  Only the Early Winters reach, which starts at the top of this photograph, has excess available water. Photo courtesy Methow Watershed Council Only the Early Winters reach, which starts at the top of this photograph, has excess available water. Photo courtesy Methow Watershed CouncilAmong the Methow Watershed Plan’s provisions is that the council be established as a legal authority to manage the Methow’s water resources, and the council has been trying to persuade the current commissioners to enact the plan’s provisions. Sheilah Kennedy and Ray Campbell were not county commissioners when the plan was accepted by the county commission in 2005. Council member Dick Ewing told the commissioners that by giving the council legal authority, they would not be signaling that they accept the 2cfs as a valid measure of the valley’s water availability but would be setting up a mechanism “that allows us to play their game.” “I’m not very interested in playing games,” Campbell replied. Okanogan County Farm Bureau president John Wyss told the commissioners that the Farm Bureau opposes the watershed council’s plan to set up an entity to administer only the Methow’s water. “We’re not Methow County. We’re Okanogan County,” he said. He added that he liked some parts of the council’s proposal but urged that the commissioners take a county-wide approach, such as creating an inter-governmental special use district to manage water. Council members have been cool to this idea, arguing that the Methow is under a unique legal constraint on water use that has not been imposed by law anywhere else in the county and that solutions must be crafted that do not apply elsewhere. “We’re a little afraid of too much government,” Knott told Methow Grist after the meeting. But he added that he was willing to explore the Farm Bureau’s suggestion. State Sen. Linda Parlette has told the council that if the commissioners do not sign on to the council’s request for legislative authority, she will not sponsor the enabling bill to give that authority to the council in the legislature, Knott told Methow Grist. That would leave the council with three options, he said: find another lawmaker to sponsor the bill, agree to join a county-wide inter-governmental special use district, or become an independent nonprofit entity “and continue as a debating society.” “We don’t like being just a debating society,” Knott said. But he added: “We’ve already put the application in.” As a nonprofit entity, the council, which has been operating on a volunteer basis since its funding from the state expired, could apply for grants, which have been being funneled through the town of Twisp. It could continue collecting water data and build water storage projects such as the one it constructed at Davis Lake and perhaps increase the dam capacity at Patterson Lake, Knott said. And it could continue to provide technical information to the county commissioners on the water situation in the Methow. What it could not do is bank water rights, which Knott described as having willing water rights holders voluntarily deposit their right in an “escrow” account that could be drawn out later by the owner. He acknowledged that the water bank proposal had been met with widespread suspicion from people who fear that once deposited, their water right can never be retrieved. County commission chair Jim DeTro expressed doubts at the meeting about the wisdom of giving up rights to a water bank. The council’s 710 gallon estimate suggests that there may be more water available in the valley basin than Ecology acknowledges, since it theoretically assumes households are consuming 5,000 gallons per day. Knott has cautioned that “Even using 710 gallons a day the 2cfs reserve will eventually be used up.” But settling the question of how much water Methow households actually use by putting meters on domestic wells also met with resistance. “It’s a slippery slope as far as I’m concerned,” commissioner Kennedy said of well metering. “We’re just putting a noose around our own necks. We’re going to prove we don’t use 5,000 gallons a day,” she said. “At what point is there a guarantee that we don’t lose our 5,000 gallons a day?” “We are not proposing putting a meter on everybody,” replied Knott, who added that he would not support any effort to remove the existing 5,000 gallons a day household and stock watering allowance. The Alice in Wonderland aspects of state water law popped out of the Rabbit Hole when Kennedy then asked: “We want the 5,000 gallons, don’t we?” “No, you don’t want them counting it [water usage] at 5,000 gallons,” Knott replied. If everyone used the allotted 5,000 gallons per day, the 2cfs reserve in most of the valley’s reaches would already have been breached, according to Knott. No one at the meeting mentioned that the State of Washington requires meters on every domestic well in the state. The Department of Ecology has never enforced that law. 10/11/2013 Comments

|