home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

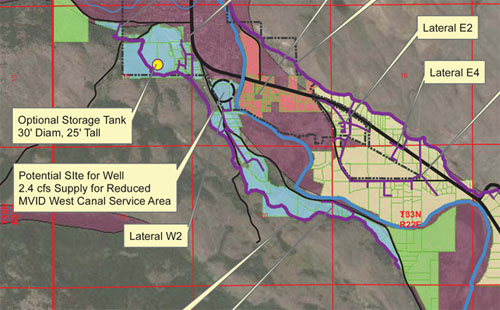

In a quiet denouement of a decades-long, high-profile drama, the century-old Methow Valley Irrigation District (MVID), once the largest in the valley, is about to become much smaller and more efficient. Eighty of the district’s 283 irrigators will be dropped from the system and put on wells, and the 12-mile long West Side Canal that traverses the hillsides above Twisp toward Carlton will be shut down and replaced by pumps and pressurized pipes, all at taxpayer expense.  Ditch master Josh Morgan cleans out the West Side Canal after a rainstorm. Photo by Solveig Torvik Ditch master Josh Morgan cleans out the West Side Canal after a rainstorm. Photo by Solveig TorvikThe story of how this happened can be read as a cautionary tale by Western water users, government regulators and the taxpayers who underwrite their activities. The Methow Valley became the focus of unwelcome national attention during a bitter water fight triggered by the 1973 passage of the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA). In the ensuing decades, valley irrigators, tribes, property rights advocates, environmentalists, and state and federal bureaucrats became entangled in complex, seemingly endless litigation and rancor over water use. Though often fought in different legal contexts, the underlying issue was whether private agricultural water rights were being seized illegally by government to restore endangered salmon runs. The valley’s other irrigation companies eventually complied with government orders to improve their water distribution efficiency. But the Methow Valley Irrigation District wasn’t one of them. It fought on. “Everybody was watching this case,” said Bunny Morgan, the MVID’s long-time secretary, who joined the district in 1991, the same year the Yakama Nation sued the Washington State Department of Ecology, the state’s water master, for failing to force the MVID to stop wasting water. Ecology and the MVID became locked in a legal battle lasting nearly a quarter of a century after Ecology in 1988 issued a stop-waste order to MVID. However, Ecology withdrew its order on promises by MVID to make improvements. The Yakama sued only after Ecology had spent three fruitless years prodding the MVID to reduce its water diversions from the Twisp and Methow rivers by 25 percent.  MVID secretary Bunny Morgan. Photo by Solveig Torvik MVID secretary Bunny Morgan. Photo by Solveig TorvikAs it turned out, a 25 percent reduction would have been a good deal for the MVID, which was wasting as much as 80 percent of the water it withdrew from the valley’s rivers, far more than comparable irrigation systems, according to Ecology. Today, after spending what MVID secretary Morgan estimates to be roughly half a million dollars in an unsuccessful legal fight, the MVID finds itself forced to operate with far less water than it had before it went to court. It now has a call on 21 cubic feet per second total from the Twisp and Methow rivers as opposed to the 53 cubic feet per second it had before challenging Ecology’s order. In hindsight, MVID director Steve Dixon told Grist, “I think we would have taken the deal we were offered a couple of lawsuits ago.” “It’s been a series of wrong decisions for a long time,” added Morgan. Had the members themselves invested in fixing MVID’s infrastructure early on, it likely would be in a much better position today, she said. But Vaughn Jolley, the chairman of the MVID board of directors who instigated the fight against Ecology in 2000, doesn’t agree. “I don’t think there was anything we could do differently” in response to what he still characterizes as Ecology’s unlawful taking of a water right. “Nobody who did it had the authority to do it,” Jolley said of the court ruling and administrative procedures that led to the present settlement, which he said constitutes an illegal adjudication of a water right. He said he fears the upshot will be that the MVID will become so small that it will become financially unsustainable. Whether or not Jolley eventually is proven correct in that prediction, there’s a near-term upside for the irrigators. The privately-owned MVID is being offered millions of dollars in public funds to modernize its long-neglected private agricultural water delivery system. And not for the first time. In the late 1990s, the MVID was offered $6 million in Bonneville Power Administration ratepayer and taxpayer funds to improve the efficiency of the irrigation system. But that effort was stymied in 2000 when the MVID under Jolley’s leadership reversed course and decided to fight Ecology rather than modernize. “They basically walked away from most of that money,” said Ecology’s Bob Barwin, an environmental engineer.  MVID directors John Richardson, left, and Steve Dixon. Photo by Solveig Torvik MVID directors John Richardson, left, and Steve Dixon. Photo by Solveig TorvikWater management “was broken at the MVID,” said Barwin. ““They didn’t have information. They knew so little of what they were doing,” he added. “They didn’t really have a good accountability over who was getting water and how much they were getting. The irrigation district put water in the canal and people just went and took what they wanted.” What’s Changing Today, beset by decrepit, inefficient infrastructure and the looming specter of liability lawsuits because of safety issues posed by open ditches—a local man was found dead in the district’s West Side Canal last year—and driven by the dictates of the ESA, a new set of MVID directors say they see no choice but to comply with government orders to modernize and become smaller if the valley’s historic irrigation system is to survive. “This is the best deal we’ve got,” said district director John Richardson, a ditch member for 15 years who grows organic fruit at Booth Canyon Ranch on the Twisp-Carlton Road. Jolley said he agrees the directors have no choice at this point. But he added that he thinks a piped gravity-fed system rather than one reliant on electricity should have been chosen. As part of the improvements, a pumping station will be installed behind the Dave Schulz orchard near Hank’s supermarket in Twisp. It will pump water uphill to a 132,000-gallon tank on Bill White’s property off Lookout Road to serve customers remaining on the system who now are served by the West Side Canal, said Morgan. Schulz and White will be compensated for having the structures on their property, she said. All told, at least $9 million will be needed to fix leakage and inefficiency problems that have festered for decades. Ecology and the federal Bureau of Reclamation have committed to providing $6.2 million in taxpayer funds for the upgrades. The rest is expected to come from other public sources.  Ditch master Josh Morgan uses an excavator in the Twisp River to funnel water into MVID's ditch. Photo courtesy MVID Ditch master Josh Morgan uses an excavator in the Twisp River to funnel water into MVID's ditch. Photo courtesy MVIDUnder a pressing deadline, the current directors are struggling with such pesky legal issues as who will be liable for damage caused by any trees that die when the leaky canals are piped and how to deal with some 80 to 90 unrecorded easements. The changes to the water delivery system must be completed by 2015 or the district risks being shut down for ESA violations. It also has been told by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to cease the practice of bringing an excavator into the Twisp River once a year as the water level drops to push up a dam to channel water into MVID canals. When the change is implemented, directors Richardson and Dixon will no longer be part of the irrigation district. Like other members leaving the district, they will be compensated by taxpayers for their costs to install wells. Only Greg Nording will remain of the directors who have overseen the change. All three men are relative newcomers to the role of ditch directors. Ecology has hired Trout Unlimited to assist MVID in finding funding and to manage the project. “We don’t get any money from MVID,” said Lisa Pelly, executive director of Trout Unlimited’s Washington Water Project in Wenatchee. But at a recent MVID meeting, Richardson expressed concern that “Trout Unlimited is not our advocate. Their contract is with Ecology.” The directors voted to ask Ecology for $150,000 to hire a project manager for two years who would represent the MVID’s interests, which Richardson said are not always the same as those of Trout Unlimited. When the district voted in 1998 to accept the $6 million to modernize, the goal then, as now, was to reduce the district’s size and install pumps, pressure pipes and screens at intakes. Screens were installed and irrigators were dropped from the system and put on wells. But the open ditches and canals were not replaced with pressure pipes and pumps, even though a USDA Soil Conservation Service study concluded as early as 1975 that the West Side Canal was “near failure.”  This pump was installed by MVID along the banks of the Methow River on the Twisp-Carlton Road in the late 1990s but was never used. Photo by Solveig Torvik This pump was installed by MVID along the banks of the Methow River on the Twisp-Carlton Road in the late 1990s but was never used. Photo by Solveig TorvikLawsuit and Though installation of pumps and pipes was started, it stopped in 2000 following a change of MVID leadership. Canal Associates brought a lawsuit against the directors who had agreed to the upgrades. Canal Associates was an MVID shareholder group formed by Jolley, a real estate developer and member of the MVID. Canal Associates sued on grounds that the directors were about to sign a contract with Ecology that called for system upgrades to be paid for by the legislature, if it appropriated the funds, according to Canal Associates’ attorney Alexander Mackie. He told Grist that the contract was flawed because it was not binding on the state but was binding on the irrigators, who would be required to pay for the mandated improvements themselves if lawmakers failed to appropriate the funds. Canal Associates also argued that it was legally improper for the directors as water trustees to sign a contract to relinquish water since they would be dropped from the district when the changes were completed, said Mackie. However, the legal issues raised by Canal Associates’ case against the incumbent directors never were tested in court. The case was settled out of court when one director was found to be ineligible to remain on the board because he was living elsewhere, said Mackie. Mike Gage was appointed by the Okanogan County Commissioners to fill the open seat, and Jolley was elected to the board.  A worker saws through an old concrete pipe to make repairs. Photo courtesy MVID A worker saws through an old concrete pipe to make repairs. Photo courtesy MVIDThe new directors reversed course and protested Ecology’s order to reduce water diversions before the state’s Pollution Control Hearings Board, claiming it was based on faulty information and was an illegal taking of water rights. “They were going to make an example of the MVID,” Mackie said of Ecology officials. And, he recalled, “There was always a fight over the amount of water coming into the district.” And there was always a fight over how much of it was going out of the system through leaks, seepage and conveyance losses. The new directors took charge at a time when the ditch system’s glaring deficiencies had been well documented. As a follow-up on the sobering 1975 Soil Conservation Service report, Ecology’s so-called 1990 Montgomery study concluded that the system had “deteriorated considerably” and was in poor condition. “The current assessment levels [on members] are not believed to be adequate for the level of maintenance required in the system,” the Montgomery report concluded. But shareholder assessments did not increase to encompass the magnitude of the infrastructure problem facing the district. The Feds Get Tough While Ecology officials unsuccessfully were badgering irrigators to stop wasting water, the federal government, running on a separate, ESA track, dropped the hammer. In 1999, William Stelle, Northwest Regional Director of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) in Seattle, shut down three of the Methow’s other irrigation districts - the Skyline, Wolf Creek and Early Winters ditches. NMFS said the ditches could not reopen until the agency completed a “biological opinion” assessment that showed they were not killing fish, which sometimes made their way into fields at unscreened intake points, according to NMFS.  When the MVID's aging West Side Canal behind Josh Morgan failed, the hillside in front of him slid onto the Twisp Carlton Road below. Photo by Solveig Torvik When the MVID's aging West Side Canal behind Josh Morgan failed, the hillside in front of him slid onto the Twisp Carlton Road below. Photo by Solveig TorvikWhen the Skyline Ditch—today operating on a pressurized pipe system—went to court to argue that the NMFS’s shutdown constituted a taking of a water right, the court said water rights were not at issue. It was the act of conveying water across federal Forest Service property that was at issue, and this conveyance right was revocable, the court ruled. The MVID is on private property and was not directly affected. But the NMFS ditch closures brought the valley’s long-simmering water conflicts to a boil. The hitherto unthinkable government closure of irrigation ditches was seen as proof by angry, fearful irrigators that their water rights could be taken away. In this toxic atmosphere, the MVID, now headed by Jolley—in defiance of an order from the NMFS, with which it was negotiating its own settlement—opened its ditches in the spring of 2000. “The ditches are going to open, period. I guess it’s civil disobedience,” the New York Times quoted Morgan as saying. The NMFS sued the MVID and levied a $55,000 fine against the ditch for violating the ESA by killing three “native” fingerling spring Chinook. A week later, the MVID agreed to a consent decree that required a reduction in its diversion of water and entered into more negotiations. Jolley told Grist he opened the ditches because he felt it would be harder for a judge to order closure of the ditches if they were already turned on and serving members. If he didn’t open them then, he said, he feared they would remain closed.  Ditches are cleaned out before water is turned on in spring. Photo courtesy MVID Ditches are cleaned out before water is turned on in spring. Photo courtesy MVIDEcology meanwhile had warned the MVID that “waste is not a beneficial use of water and therefore no water right exists for the amount inefficiently managed.” But the MVID directors were not persuaded. Jolley said he enlisted the Pacific Legal Foundation, a property rights advocacy organization, and the Washington Agricultural Legal Foundation to help fight Ecology. The irrigators complained that the power costs of operating a new pressurized system would be too high to bear. They also argued that water escaping from the unlined ditches was not lost, it was recharging the groundwater. That common assertion was discounted by expert testimony accepted by the state’s Pollution Control Hearings Board stating that water lost from the ditches may indeed recharge groundwater, but not for use where and when it’s needed by other legally entitled users. Jolley made it clear at the time that irrigators felt it was unfair to blame them for the salmon’s demise. “We certainly want to do everything we can to help endangered species. And when salmon survive ocean overharvest, sports fisheries, Arctic terns, Indian nets, major Columbia river dams, and NMFS hatchery killings, we certainly wouldn’t want one to perish” in the valley’s irrigation ditches, he told the Associated Press in June of 2000. In 2002, when Ecology issued its stop-waste order, the irrigators’ ire intensified. The MVID filed personal suit, later dropped, against two Ecology officials working on the case, Barwin and Tom Tebb, for unspecified constitutional infringement. “These agency people, both state and federal, are nothing but liars, cheats, bullies and thieves,” director Mike Gage, who has since left the valley, told the Wenatchee World. Lessons Learned  This photo shows how the Maltais Flume was lined to stop leaks. Photo courtesy MVID This photo shows how the Maltais Flume was lined to stop leaks. Photo courtesy MVIDAsked if in hindsight he would handle the case differently, Barwin told Grist: “Maybe we should have taken some kind of enforcement action in the early `90s.” And, he added, had the agency employed a legal mechanism that would have prevented the district from reversing course after it agreed to modernize, “We could have avoided quite a bit of what happened.” Barwin does not dispute that Ecology’s enforcement efforts against MVID blew hot and cold over the years. “We were also wearing another hat,” he noted; Ecology was trying to provide the irrigators with funding for upgrades. “We never quite found the right dose of carrot and stick…The judgment has to be on us for how we did that.” As for NMFS’s Stelle, if he had ditch closures to do over again, “I would have spent more time in my dusty boots walking in the fields and talking solutions with farmers,” he said. “I think it’s a point of encouragement that the community is owning its future and deciding, both for good business reasons and good environmental reasons, that making these changes to significantly improve efficiencies is a good thing to do,” he added. The OWL Factor Of the major players in the drama, only the three-member, Carlton-based Okanogan Wilderness League (OWL) headed by president Lee Bernheisel hints at more trouble to come. Bernheisel raises alfalfa at the old terminus of the West Canal near Carlton. For years he had ongoing small claims court disputes with the MVID over its failure to deliver the water he was paying for to the end of the line where he lives. In 1999, he left MVID’s system and put in a well. He’s long been active in urging that the MVID be required to stop wasting water. OWL sued Ecology for failing to force MVID to stop wasting water. The state’s Pollution Control Hearings Board sided with OWL, ordering Ecology back to the drawing board to rework its analysis of how much water the MVID could have.  A portion of the overview map of the MVID modernization plan. Click for full map. Image courtesy MVID A portion of the overview map of the MVID modernization plan. Click for full map. Image courtesy MVIDAt the time, the MVID was withdrawing a whopping 28.1 acre-feet of river water for every acre irrigated. (An acre foot covers one acre with one foot of water.) The rest was lost to leaks, evaporation or in transport, according to findings of fact stipulated in a ruling by the Pollution Control Hearings Board. But alfalfa grown in the valley needs only 1.8 acre feet annually and pasture needs 2.2 acre feet, according to Ecology’s Montgomery study. “The end really is not in sight as far as we are concerned,” said Bernheisel, who noted that some parts of the new plan “are very good.” But, he told Grist, “We are not at all pleased” by the prospect that when Ecology’s final determination is made on how much water the reorganized MVID is entitled to, it may be allowed to take water for as much as 1,350 acres when it only irrigates 881 acres. The district today levies an assessment on members that’s equivalent to $116 per acre on what the district claims as total acreage of 1,350, according to director Richardson. But some district shareholders are not irrigating their lands, so Ecology puts the district’s irrigable acres at 881.  A portion of one of the five detailed maps of the MVID modernization plans. The maps are available at the MVID website. A portion of one of the five detailed maps of the MVID modernization plans. The maps are available at the MVID website.Bernheisel argues that non-irrigating MVID shareholders who are paying assessments in the belief that they’re reserving water rights should not be counted by Ecology as irrigators when it issues its final determination of the amount of water the reduced district is entitled to take from rivers. Barwin told Grist that irrigation district water rights are not owned by any member alone, so district shareholders who don’t use their water allocation are not preserving a water right. They instead are reserving a right to call for water delivery from an irrigation district, according to Barwin. But he cautioned: “That does not give the district the right to deliver the water.” When the amount of water to be allocated to the reorganized MVID finally is settled, the district itself will decide how to allocate it among users. “We do the wholesale part. They do the retail part,” said Barwin. In 2005 the MVID’s appeal of Ecology’s 2002 order to stop wasting water were dismissed by Okanogan County Superior Court Judge Jack Burchard, who said: “…much of the District’s argument can be reduced to a simple proposition which is obviously absurd: we have the right to be inefficient and being inefficient gives us the right to more water than we need.” Even so, the MVID fought on. In 2011, after more years of unsuccessful negotiations and just two weeks before the case was scheduled for hearing before the Washington State Supreme Court, the MVID’s current, newly-elected directors and Ecology settled their differences. The irrigation district agreed to modernize, reduce its water use and to measure and report all flows into its canals. Ecology agreed to assist the MVID in paying for the upgrades. MVID ditch master Josh Morgan, (secretary Bunny Morgan’s son) said people often tell him that he can’t run the irrigation district on such a severely reduced water allocation. But he told Grist he thinks he can. “To me that’s a fun challenge.” 7/12/2013 Comments

|