home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

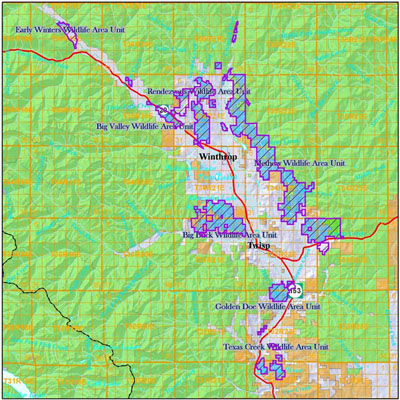

Tom McCoy stands by a 75-95 year old ponderosa pine in a demonstration forest thinning project behind Bear Creek Campground. Before fire supression started there would have been 11 trees per acre in this spot, not the 1,000 or more seen behind him. Tom McCoy stands by a 75-95 year old ponderosa pine in a demonstration forest thinning project behind Bear Creek Campground. Before fire supression started there would have been 11 trees per acre in this spot, not the 1,000 or more seen behind him.Circle Back A small grant to help answer big questions was among those recently announced by the Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program. But it takes a dusty ride in Tom McCoy’s pickup truck to understand how $309,750 could help restore the forest and protect the Methow Valley from “catastrophic forest fires,” as the paperwork states. McCoy is the manager of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Methow Wildlife Area. That means he is responsible for the health of the plants and animals that live in, and the humans who use, approximately 34,000 acres of land. Between 15,000 and 16,000 of those acres are in the WDFW Methow Unit on the east side of the valley. They lie in an 18-mile strip with federal forest on the backside and the settled valley out front, including the stretch from Winthrop to Twisp. The Methow Unit is where the grant money will be spent.  This piece of land about 1/4 mile from Cougar Flats is the only acre in the Methow Unit that looks similar to what tree density once looked like throughout the area, according to Tom McCoy. This piece of land about 1/4 mile from Cougar Flats is the only acre in the Methow Unit that looks similar to what tree density once looked like throughout the area, according to Tom McCoy.The “grand scheme,” McCoy explains, is “to the greatest degree possible, prepare the forest for fire—either prescribed or natural” and then do restorative burning. He is anxious to inform the public about the project, partly because so many private landowners sit on acreage that needs similar treatment if they are to avoid catastrophic fire. The Methow is one of two areas in Okanogan County with a forest restoration demonstration project on state land. The other is in the Sinlahekin Wildlife Area near Tonasket. McCoy says that on his first day on the job (Oct. 1, 2008), it was immediately apparent to him that “the condition of this forest is probably the single biggest issue for the health of the area.” What he, a plant specialist, saw that day was a sick forest suffering from decades of wildfire suppression that had left it overcrowded, open to pine beetle attack and the growth of understory plants that have eased out the ones that should be flourishing—in other words, a candidate for a very hot fire. In one area more than 1,000 acres in size, McCoy found 40 percent tree mortality and “virtually all the trees under beetle attack.” But, he says, there is hope for the patient. His first step was to launch, in 2009, an experimental tree-thinning project on a seven-acre test plot adjacent to the 2005 600 acre Pearrygin Fire. That fire started at the shooting range and spread into the Pearrygin Forest, part of which already had been heavily thinned. However, the thinned area was consumed, too. But the understory diversity “exploded” with species richness in the thinned portion after the fire, McCoy says. As he pulls the truck into the woods above WDFW’s popular Bear Creek campground, where the test plot is located, McCoy points toward acres of short trees growing so close together that their stick-like trunks look like lodgepole pine instead of the ponderosa they are. Then he drops this factoid bomb: Instead of this thicket, which has at least 1,000 or more tree trunks per acre, there should be only 14 trees per acre on average. In fact, he adds, the historical density in this very spot was about 11 trees per acre.  As part of a two-step forest restoration project, the ponderosa pines marked with orange paint will remain and all other trees will be cut down to prepare a 120-acre piece of Cougar Flats for a planned fire. As part of a two-step forest restoration project, the ponderosa pines marked with orange paint will remain and all other trees will be cut down to prepare a 120-acre piece of Cougar Flats for a planned fire.He then turns toward the test plot and says, “This is what it used to all look like”—a scattering of much taller trees, in this case 75 to 100 year old ponderosa. As time allows, McCoy and others are saving the healthiest, oldest trees plus a few younger replacements and cutting everything else. Their hope is that the ponderosa will thrive and that the natural understory will return. Early indications are positive. And what to do with hundreds of downed trees? The public can buy a $10 permit good for a year and come salvage any “wood on the ground,” McCoy said. (No cutting of live trees is allowed.) So far local homeowners who want firewood and furniture makers, who’ve come from as far as Wenatchee, have hauled wood away. “The more they take, the happier we are,” McCoy said. Historical Tree Density How can anyone know the historical density of trees in a specific forest? Because a couple of years back Derek Churchill, a forestry consultant hired by the Wenatchee Nature Conservancy and contracted to WDFW, helped figure it out. McCoy said that as part of the study, three-to-four hectare plots were established and “every 1890 vintage or older tree, including stumps and wood on the ground” was surveyed to find out what the forest looked like before the policy of suppressing fire began. (A hectare equals approximately 2.5 acres.)  Historically, low-intensity ground fires swept through here about every 10 years on average, says Tom McCoy, as he points to this old ponderosa pine's record of valley fire history. Each blackened ridge is from such a fire. Historically, low-intensity ground fires swept through here about every 10 years on average, says Tom McCoy, as he points to this old ponderosa pine's record of valley fire history. Each blackened ridge is from such a fire.Historically “fire came through frequently,” McCoy explains as he drives toward a nearby spot with “one of the most interesting trees in the wildlife area,” to prove his point. “There are very, very few trees here over 175 years old,” he says, standing next to one such survivor. The base of the towering, thick-barked ponderosa was damaged at some point, creating a hollow where, in addition to later damage at the hands of someone’s axe, it’s possible to see “the fire history of the valley.” Numerous black fire scars are visible between narrow growth bands from periods without fire. “Every seven to fifteen years low-intensity ground fires came through here,” he says. (Churchill found that the last such fire came through the area in 1918.) Those fires have been replaced by huge, catastrophic fires of an intensity that once was confined to higher elevation fires in lodgepole pine forest, says McCoy. He then points toward a nearby stand of aspen trees that is healthier than most. Aspen should be much more prevalent here, he says, adding that they need fire to remain healthy and are called “the Phoenix tree.” Without fire, aspens, which need full sun, get shaded out by an overarching canopy of ponderosa pine and Douglas fir. And at the root end they get more competition for nutrients. “A very healthy aspen stand can regenerate [after a fire] in the range of 30,000 to 40,000 stems per acre,” McCoy says.  The grant money will pay for forest rehabilitation work in the Methow Wildlife Area Unit. -CLICK TO ENLARGE MAP- Image courtesy Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife The grant money will pay for forest rehabilitation work in the Methow Wildlife Area Unit. -CLICK TO ENLARGE MAP- Image courtesy Washington State Department of Fish and WildlifeChurchill’s work to figure out what the original forest looked like was augmented with the help of Andrew Larson, a forestry professor from the University of Montana, who last year brought a group of his advanced students to the Methow Valley. The students compared what the forest used to be like with its present state. “We can identify what the canopy gap [the distance between trees] was and how they were clumped,” McCoy says. Armed with specifics, Churchill and the students wrote a prescription for restoring the health of one forest area near Cougar Lake. And the recently approved grant will help treat that 120-acre section of Cougar Flats, a popular deer hunting area, as a demonstration project. Phase one includes thinning all 120 acres. As McCoy pulls into Cougar Flats, trees marked with orange and blue paint appear alongside the road. Orange means leave the tree, blue means cut it down. Look at the trees marked with orange and “imagine everything else gone,” McCoy says. “Ninety five percent of the trees you see here are going to go.” This fall or winter, after the ground freezes so soils won’t be disturbed, a commercial timber harvest is planned. There are a couple more steps to complete before a contract goes out for bid. Meanwhile some grant money will be used to finish marking the trees. As for the “tens of thousands” of small-stem trees that won’t be worth a logger’s time, McCoy says one option would be to grind it for hog fuel. Or “have the mother of all firewood sales” if the wood can be stacked and decked. The timber harvest will prepare the forest for phase two of its restorative cure—an intentional burn, perhaps the following year. If McCoy’s mini-experiments are indicative, that fire will help restore tree health and the understory essential to support populations of native birds and animals. Assuming the project goes as planned, McCoy says he will spend the next four years treating about 4,000 acres of unhealthy forest on WDFW land. 7/18/2013 Comments

|