More than 30 local school district employees, law enforcement officials and community residents watch a training film used at the recent suicide intervention/prevention workshop sponsored by Room One. More than 30 local school district employees, law enforcement officials and community residents watch a training film used at the recent suicide intervention/prevention workshop sponsored by Room One.

story and photos by Karen West

The recent outpouring of community support for preventing suicide in the Methow Valley has lead Room One to announce plans to put together a community suicide response plan. It will include intervention with those having suicidal thoughts as well as resources for post-intervention support, according to Karissa McLane, executive director.

Okanogan County had 14 verified suicide deaths in 2011 – “almost triple the number in 2010,” according to Laurie Jones, community health director for Okanogan County Public Health. Jones sifted through county death records to compile January through December 2011 statistics for Grist and found nine self-inflicted gunshots, four hangings and one non-accidental drowning. In 2010 the county had five suicides, all self-inflicted gunshots, Jones said.

She added that there are two toxicology reports pending for deaths in 2011, plus six more deaths by acute alcohol intoxication and medication poisoning that are disturbing to her. Jones thinks the data is skewed by the prevailing practice of treating most overdoses as accidental. “Marilyn Monroe’s death would be considered accidental,” she said.

The statistics include neither Okanogan County residents who killed themselves in other counties, nor the deaths of people with local ties whose deaths have local impact.

Alarmed by those numbers and looking for solutions, McLane and Lois Garland, who is the on-staff family empowerment person for the school district, attended a suicide prevention workshop led by Sabrina Votava from the state’s Youth Suicide Prevention Program office in Spokane.

Impressed with what they learned, Room One invited Votava to come to Twisp earlier this month to present a public forum and a three-hour prevention workshop. They said they had no idea what to expect. The response was a standing-room-only crowd of more than four dozen people at the Cinnamon Twisp Bakery. The next morning about three dozen people, including teachers and local law enforcement officers, received practical training in recognizing when someone is considering suicide and ways to intervene.

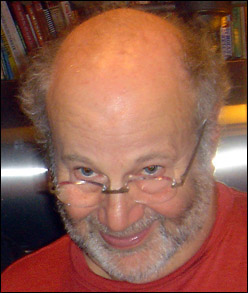

Sabrina Votava, who works for the state's Youth Suicide Prevention Program, came to Twisp to lead two days of community education and training.

Votava didn’t share her personal story with her local audiences, or reveal that her parents, Sandy and Dave Ross, were in the room, proudly listening to their daughter, who dedicated her life to suicide prevention work after losing two brothers to suicide in 2003.

Votava was a freshman at the University of Washington when Zach, 22, and six months later, Kacey, 23, hung themselves. She was the last person both boys contacted, and she and the rest of the family were stunned by their deaths.

After Zach’s death they made a pact with Kacey, his mom said, “Promise if you have any of these thoughts you’ll talk to us or to someone else.” He didn’t keep his promise.

Sandy Ross descended into alcoholism for two years. “I thought it was my fault,” she said, now recovered. “I was a bad mom. It’s not true. And Dave is a wonderful dad.”

Dave Ross said he found the Out of the Darkness Overnight Walk, sponsored by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, a helpful part of his healing. Participants walk and talk all night, from dusk until dawn, symbolically bringing the subject into the open. (www.outofthedarkness.org)

Now that she’s had training, and with 20-20 hindsight, their daughter said, “It’s easy to see some signs and symptoms we missed.” She added there is a family history of mental health issues on her dad’s side. His mother was bi-polar.

“Most of the time there are signs” someone is considering suicide, Votava told her first audience. She acknowledged the pain and guilt surviving family and friends feel when they were oblivious or couldn’t stop a suicide. “We just have to forgive ourselves,” she said.

Votava’s purpose in Twisp was to teach how to recognize signs of suicidal thoughts, intervene and get that person to help before they engage in suicidal behavior. She told workshop trainees it was not their job to literally save lives but to get the person with suicidal thoughts “in touch with someone who can help them save their own lives.”

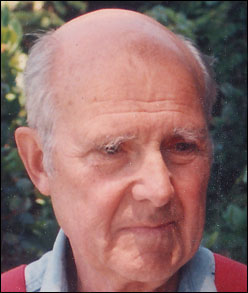

David and Sandy Ross lost two of their four children, sons Zach and Kacey, to suicide in 2003 six months apart. Sabrina Votava is their daughter.

And how does that happen? The first step is to pay attention. Listen for the signs.

“Depression is the number one risk factor for suicide,” Votava said, adding that in young people going through puberty it can be difficult to distinguish between normal behavior and the signs of dangerous depression. She explained by listing such signs as irritability, anxiety, anger, acting out, drop in school performance, a hard time focusing, over-reaction to criticism, frequent physical complaints and unexplained joint pain.

Some serious signals she cited could be black and white thinking such as, “I didn’t get an A. I failed.” Or a person who doesn’t see good in the world. A sense of hopelessness. She called bullying a risk factor for suicide for both the bully and the victim of bullying. “Victims of bullies are much more likely to try suicide,” she said.

Additional warning signs Votava listed are talking about suicide, someone saying they feel like a burden, that they wish they could be gone, talking about death, giving away prized possessions, increased isolation, increased drug or alcohol use, a sudden change in behavior, or suddenly feeling better, which means they “may have decided to do it and feel hope.”

She also cautioned, “If someone has made an attempt before, they are likely to do it again.”

The second step toward saving lives is to be direct. Ask questions, Votava said. “Are you thinking about suicide? Are you thinking of killing yourself? Have you been thinking about suicide? Are you thinking about it right now? Are you feeling so bad you feel hopeless?”

“The only way we’re going to know if they’re thinking about suicide is to ask...They want to talk about it with you but there is so much stigma and taboo surrounding this.”

Show you care: “Are you really thinking about suicide? Because if you are, I want to help you. I’m comfortable with this topic and with getting you some help. Thank you for sharing that with me. Tell me more. I’m sorry you’re feeling so bad.”

The third step, Votava said, is to keep the person safe. You might say, “This is an issue bigger than both of us.” “We need some help.” Call for help.

“Don’t leave them alone unless you are in danger... It’s important to be patient and persistent,” she added. And if there are guns in the house, get them out. Local police will put them into safe keeping if you are not comfortable keeping the weapons yourself.

Megan Schmidt, a psychologist and licensed mental health counselor with a local practice, said she asked her suicidal clients what they would like the general public to know. First, she said, was “to make no assumptions at all about who a suicidal victim might be. In this community it could be anybody.”

Their second bit of advice was to intervene more than once. The suicidal person has ambivalence about living and dying, Schmidt said. “I don’t doubt they want to be out of pain. But they might want to keep that option [suicide] in their back pocket in case this help doesn’t work out.”

The third thing her clients want the public to know is that “when someone has an entrenched depression, they can’t think well. They can’t reason. There are cognitive changes,” she said. “Appreciate that and don’t lose patience.”

Votava said brain scans show that people who are in emotional pain and thinking suicidal thoughts have muddy thinking. But if they can be brought out of whatever mental health episode they’re having, they might make different decisions.

When asked about the terminally ill and elderly people who say they want to die, Votava said she considers it a different subject. “That’s a discussion you need to have in your community and decide for yourselves.”

It’s against the law in Oregon and Washington for a lay person to advocate or assist someone who wishes to die. Those in the workshop were advised to refer the person to their doctor, who can determine what’s going on.

Raleigh Bowden, M.D., is helping assess the need for in-home care givers, support services and medical help for the valley’s aging population in addition to seeing clients. She says it’s important to remove depression and pain as the reason for suicidal thoughts. If depression and pain are treated, especially for the elderly, sometimes the desire to end life goes away, she said.

Asked later for her thoughts about the response of the Methow Valley people who came to hear her speak, Votava said, “It was really great to see the community pulling together. I know there’s been hurt and pain, but I saw a lot of caring and concern. I see a lot of hope in that.”

comment on this story >> |

David and Melissa McWalter with their children (L to R) Thomas, Ian, and Mariah, and their dog, Tonor, last summer at Deception Pass. Before the end of the year Melissa took her own life. Photo courtesy of David McWalter.

David and Melissa McWalter with their children (L to R) Thomas, Ian, and Mariah, and their dog, Tonor, last summer at Deception Pass. Before the end of the year Melissa took her own life. Photo courtesy of David McWalter. More than 30 local school district employees, law enforcement officials and community residents watch a training film used at the recent suicide intervention/prevention workshop sponsored by Room One.

More than 30 local school district employees, law enforcement officials and community residents watch a training film used at the recent suicide intervention/prevention workshop sponsored by Room One. Sabrina Votava, who works for the state's Youth Suicide Prevention Program, came to Twisp to lead two days of community education and training.

Sabrina Votava, who works for the state's Youth Suicide Prevention Program, came to Twisp to lead two days of community education and training. David and Sandy Ross lost two of their four children, sons Zach and Kacey, to suicide in 2003 six months apart. Sabrina Votava is their daughter.

David and Sandy Ross lost two of their four children, sons Zach and Kacey, to suicide in 2003 six months apart. Sabrina Votava is their daughter.