|

Susie Stephens Trail

Proving to be a Long Walk

by Solveig Torvik

Comment on this story >>

Winthrop town planner Rocklynn Culp on the Spring Creek Bridge. - Photo by Solveig Torvik The imposing new linchpin of the Susie Stephens Trail, Winthrop’s $2.75 million Spring Creek Bridge across the Methow River, finally is completed.

But what’s happening with the trail itself?

In addition to the cost of bridge construction, (which includes ancillary expenses such as geotechnical work, inspections, and project management services) the town has spent $445,000 on design, construction and acquisition of trail rights-of-way and easements across seven private properties, according to Winthrop town planner Rocklynn Culp.

Nonetheless, the years-long goal of linking downtown Winthrop with its post office and grocery store by a safe, walk-able, bike-able trail has hit some snags. A major obstacle to completing the trail as planned is that an eighth property owner, Fodor Decedents Trust, which includes owner Stephen Fodor, co-founder of the California bio-tech company Affymetrix, refuses to sell the approximately 600-foot long, 20-foot wide right-of-way or grant an easement that’s needed for the trail to cross his land, according to Culp.

The other hurdle is that after the trail is built to the edge of White Avenue adjoining the Winthrop Physical Therapy building next spring, the town will have no more money to finish the trail.

And then there are the concerns raised by Foghorn Ditch trustees, who say the town has not adequately responded to their fears that the trail will harm ditch operations.

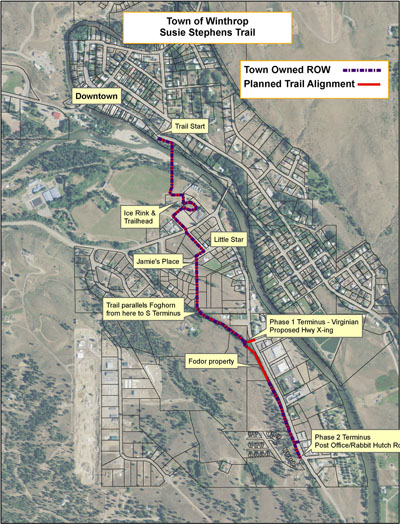

The Susie Stephens Trail is supposed to run from the Methow Conservancy downtown nearly to the town’s southern limits along the west side of Highway 20, ending at the post office. But as matters now stand, it comes to a halt across the highway from the public right-of-way that lies between the Virginian and Pardners Mini Market. With the exception of the Fodor property, all the rights-of-way or easements needed for the trail have been purchased by the town – including one final parcel beyond the Fodor trust holdings that would take the trail to the post office.

The Fodor refusal blocks the town from continuing the trail as planned on the west side of Highway 20 to its southern termination. Yet the town already has paid Uplands LLC $15,400 for that land, which for now at least, has become an unusable right-of-way along the west side of Highway 20 because it lies south of the blocking Fodor property.

It’s unclear whether the trail alternately might be built across Highway 20 from its intended route and instead run in front of the mini market, grocery store, hardware store and motel to reach the post office. The present state funding source requires that trails be separated from highways, notes Culp. At any rate, the plan now calls for some kind of pedestrian crossing between the Virginian and Pardners Mini Market.

Beyond the new bridge, the trail crosses land that, for the moment, lies partly in the county and is owned by the Belsby family of Spring Creek Ranch. It skirts around the ice rink and Winthrop Physical Therapy building, crosses White Avenue and runs along the west side of Norfolk Avenue adjoining vacant land owned by Val Varney. No money changed hands here because the town owns a 60-foot easement along Norfolk Avenue, according to Culp.

The trail briefly jogs right across from the Wellness Center, then turns left to pass Jamie’s Place on the east. It crosses vacant multi-family zoned land owned by Rick Le Duc, then follows the Foghorn Ditch southeastward toward Pardners Mini Market on land owned by Eleanor Akker that was annexed by the town from the county and rezoned commercial. Beyond the Fodor property, the town also bought trail right-of-way from Uplands LLC (now owned by the Sukovaty family, which irrigates from the Foghorn Ditch) and the Cascade Condos.

Fred Wert is standing where the proposed Susie Stephens Trail now apparently will end, adjoining Highway 20 and across the public right-of-way between the Virginian and Pardner's Mini Market. The trail will come through the trees, some of which may be removed. The Foghorn Ditch runs in the background behind the trees. - Photo by Solveig Torvik Fred Wert is standing where the proposed Susie Stephens Trail now apparently will end, adjoining Highway 20 and across the public right-of-way between the Virginian and Pardner's Mini Market. The trail will come through the trees, some of which may be removed. The Foghorn Ditch runs in the background behind the trees. - Photo by Solveig Torvik

One and one-fourth miles long, the trail will be 12 feet wide and paved with asphalt. That’s because under terms of the funding from the state’s Recreation and Conservation Office, (RCO) the trail must be handicapped accessible. And in winter, at least five to six feet of it will have to be kept cleared for pedestrian and handicapped access.

“That’s what we signed up for and that’s what we need,” says Culp.

Funds remain to complete paving of the trail from the bridge past the ice rink and Winthrop Physical Therapy to the edge of White Avenue next spring, says Culp. The town will seek more funding to complete the trail from there.

Town officials also must deal with the consequences of the impasse with the Fodor trust. The town has the option to invoke eminent domain to obtain the right-of-way, but the state funding it receives does not pay for legal costs, according to Culp. (Attempts to reach Stephen Fodor for comment were unsuccessful.)

And the clock is ticking. Under terms of its RCO funding from the Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program, the town has until 2015 to finish building the trail, adds Culp. However, she says the town can apply for an extension. “My understanding is that as long as we are making every effort to use the acquired property for its intended use, we will be able to remain in good standing with RCO.”

Meanwhile, difficulties with irrigators on the Foghorn Ditch further complicate matters. The trail, which follows the ditch for 1/8th of a mile on property owned by LeDuc, Akker, Fodor, Uplands and Cascade Condos, will cross the irrigation ditch over two bridges, Culp says.

Foghorn Ditch trustees Danny Yanarella, Louis Sukovaty and Bob Gronninger have since 2009 been requesting – unsuccessfully, they say - that the town of Winthrop provide detailed design information that would show any possible impact on ditch operations. Among their concerns is that trail construction might undercut and breach the ditch, that the trail will run so close to the ditch that it will become impossible to bring in heavy equipment for maintenance, and that the trail will entail legal liabilities, and create additional expenses, for the ditch company, which consists of 55 irrigators.

The full Susie Stephens trail is intended to run from the Methow Conservancy south to the Winthrop Post Office. - Map courtesy Winthrop Planning Department. Click Map to EnlargeThe irrigators have a prescriptive easement to carry water in the 80-year old ditch, and they also claim a 25-foot easement in each direction from the ditch centerline, used for maintenance and repair. The trustees conceded in a March 23, 2010, letter to the town that the 25-foot easements are not “stated consistently in title documents for all parcels crossed by the ditch.” But they argue that “the ditch line and easements are clearly defined on maps for various segments of the ditch.”

The trustees have asked that the town “not initiate or conduct any construction or disturbance within or affecting the Company’s ditch easement without the Company’s written agreement.”

That agreement has not been forthcoming, and the trustees said in a statement to Grist last week that the town is proceeding “in a manner that appears to hold the Ditch’s concerns without merit,” leaving “management and members confused about why the Town is expending money to acquire easements and develop a trail plan without first comprehensively addressing and resolving Ditch concerns.”

Winthrop Mayor Dave Acheson says the town does not yet have a detailed design for that portion of the trail, but the town has told ditch trustees that it wants to work with them to develop a design that addresses their concerns. He characterized their response as: “`You don’t have a design, don’t waste our time’… It’s been frustrating.” Still, he says, “I view it as an ongoing discussion,” and he adds that the town is “very sensitive” to the irrigators’ concerns about possible increased ditch maintenance costs.

The right-of-way the town bought near the ditch is 20 feet wide, and Acheson says that aside from where the trail crosses the ditch, it generally will run between 10 to 20 feet from it.

Asked about the trustee’s claim that they have a 25-foot easement from the centerline on both sides of the ditch, Acheson says he’s been informed by the town’s attorney that a prescriptive easement “doesn’t mean anything until you go to court and have it perfected.”

The trustees have asked the town to pay for the cost of liability insurance, but Acheson says that would be illegal. “It’s a gift of public funds. We’re not responsible for them having an open ditch.”

A little back story:

Rocklynn Culp, Winthrop town planner, led the paperwork process that resulted in construction of the Spring Creek Bridge. - Photo by Solveig Torvik The need for a trail from downtown to the southern town limits had been discussed long before she became town planner 12 years ago, according to Culp. Her understanding is that the Washington State Department of Transportation became concerned when handicapped people in motorized wheelchairs were using Highway 20 to travel from downtown to the post office, putting themselves in danger and causing traffic obstructions.

However, the DOT chose to view this as the town’s problem, not theirs, according to Culp, and there never appears to have been consideration of using the state’s power of eminent domain to build sidewalks along the highway. “They have mainly looked to us to be in the driver’s seat to solve the problem,” Culp says.

Paul Mahre, local programs engineer with the DOT in Wenatchee, has been providing oversight for the bridge project for the town since 2003. “Cities build sidewalks,” he says, not state highway departments. The DOT has only a prescriptive ownership of the land on which the highway pavement sits, plus the shoulders, according to Mahre. And the two-foot shoulders along Highway 20 means “it’s really dangerous for bicyclists and pedestrians,” he says. When finished, the bridge and trail project “will be a great facility for bicyclists and pedestrians,” he adds.

Informal studies were undertaken by the town in the late 1980s to consider where a safe trail could be built. Initially there was discussion of a trail that followed the river, along the horse corral south of the Winthrop bridge that crosses the Methow River. But that idea was discarded as it became too complicated with ownership and other issues, says Culp, who initially cut her teeth on Winthrop’s trail project in the late 1990s while working as a consultant for Highlands Associates Inc. of Okanogan.

The project got under way in 1999 when the town received a $160,000 federal enhancement grant to design the bridge and do environmental studies; that grant was funneled through the DOT. By 2001 the town had a study in hand from Sahale LLC, the bridge and trail construction firm that in 1995 built the Tawlkes-Foster Bridge near Mazama. In 2002 Culp was hired as the town’s planner. The same year, Susie Stephens, a bicycle safety proponent who worked for the Methow Conservancy, died in a traffic accident, and the town decided to name the trail in her honor.

Susie Stephens was a bicycle safety proponent who worked for the Methow Conservancy. The passage of a gas tax measure in 2005 “was our first lucky break,” relates Culp. State Sen. Mary Margaret Haugen, who owns property in the valley and was familiar with Winthrop’s pedestrian safety issue, was chair of the Senate transportation committee. After Culp petitioned Haugen’s committee for assistance with the town’s safety problem along the state’s highway, Winthrop received a $1.4 million grant that served as seed money for the trail project.

However, the money was given to the DOT as lead agency, and its engineers informed the town that the bridge would cost closer to $3 million, considerably more than Sahale’s $1.8 million estimate – which did not include ancillary costs such as project management services. This disagreement over projected cost caused the town to ask the legislature to give it control of the project on a design-build basis, according to Culp. Typically these one-stop design-build contracts are used on much larger projects, according to Mahre. But permission was granted, though DOT retained oversight of the project in what Culp describes as a generally “good” working relationship.

The bridge, designed from the outset with the intention of carrying water and sewer lines across the river, has had more than its share of construction troubles. Carroll Vogel, owner of Sahale, which held the first design-build contract, died while work was underway. After new bids were sought, a Woodinville firm, Mowat, was then hired to complete the bridge.

Mowat altered the design of the bridge underpinnings, which turned out to be less environmentally intrusive and less disruptive to highway traffic than the Sahale design, according to Culp. Mowat’s approach did not require as much concrete to be poured because the bridge anchors were drilled into the ground at an angle, she explains.

“The reason for the trail is to have a way to get from town to the post office and grocery store without having to walk on the highway with your three-year-old,” says Fred Wert, a long-time rails-to-trail proponent who chairs the town’s Susie Stephens Trails Committee. (Other committee members are Brad Garner, Chris Hartwig, Dan Kuperberg, Jane Gilbertson, Jay Lucas, Kristen Smith, Lance Christensen, Mac Shelton and Mel Hartwig.)

Wert in 1989 helped draft the enabling legislation that funneled state money into public trail development for dispensation by the Recreation and Conservation Office, which has been in existence since 1964. Over the last 20 years, $60 million has been disbursed by the RCO in the Methow Valley for various projects such as Winthrop’s ice skating rink, the Twisp trails project and the Wagner pool, according to Wert, former director of the Washington Chapter of the Rails to Trails Conservancy and author of Washington’s Rail-Trails.

“It’s amazing for a small community to carry off such a project,” says Wert, who’s been involved in planning half of the state’s rail-trail’s projects. Still, he says he thinks the town’s process could have been more transparent. “The project would have benefitted by more public participation,” he contends.

John Hayes, a leading force behind the Methow Valley’s ski trail network, says he thinks the town has run a transparent public process. It held open houses to explain the project, he notes, though they weren’t as well attended as they might have been.

Hayes, who stepped in to serve as pro bono negotiator for the town with the Belsby family when negotiations with the DOT broke down early in the process, says he’s preparing the paperwork to have the town annex the Belsby property that adjoins the bridge.

Hayes recalls that the town knew by the late 1980s that it eventually would have to replace the five-inch siphons that are part of the system that carry sewage under the Methow River near Heckendorn, and from the outset the bridge was considered as the solution to that problem. Attaching sewer and water pipes to a bridge is cheaper and less environmentally intrusive that digging under the river, he says. “Major excavations of the river just don’t take place any more,” he adds.

Hayes has high praise for Culp’s role in shepherding the project over the years. “I think Rocklynn’s a genius. The town’s very lucky to have a planner like her. I would not have the patience to do this,” he adds, alluding to the complex permitting, grant writing and funding process that’s gotten the project to where it is today.

And he says he’s optimistic that the Susie Stephens Trail will become a reality.

“It took 23 years to get the right-of way for the Methow Valley Community Trail,” he reminds. “I feel if you give them enough time, people come to their senses. That’s been proven with the Community Trail. People come around.”

12/13/11

|