home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

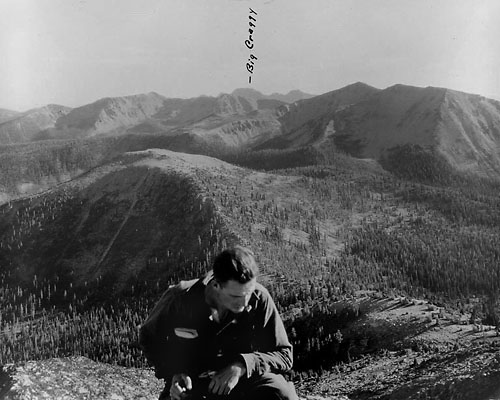

Someone turned a camera on Wernsted (smoking the cigarette), his gear and crew in this photograph taken in 1924. Notice the rock cairn on the right, probably built by Lage. Someone turned a camera on Wernsted (smoking the cigarette), his gear and crew in this photograph taken in 1924. Notice the rock cairn on the right, probably built by Lage.Lage Wernstedt Long ago, during what I would describe as one of the less socially productive periods of my life, I remember engaging my father in a late night debate concerning the leadership qualities of a then-popular media figure named Abbie Hoffman. As our discussion wound to a halt I recall him placing a hand on my shoulder and saying “choose your heroes carefully.” It was advice I took seriously and I am happy to say that I live in a place where I have encountered —both literally and literarily—more than a few people whose character I think even my father would have found admirable. In fact, our local history fairly abounds with men and women whose modesty, courage, tenacity and mastery of craft made them the stuff of legend. Yet, oddly enough, the person whose exploits and accomplishments would most seem to achieve heroic status remains little known and largely absent from Methow history.  Another Wernstedt image from the Pasayten Wilderness, this one entitled “Diamond Point”. The man shown is likely Wernstedt himself. Another Wernstedt image from the Pasayten Wilderness, this one entitled “Diamond Point”. The man shown is likely Wernstedt himself.The fault probably lies with Lage (pronounced “Loggy”) Wernstedt himself. Called ”one of the most remarkable individuals ever associated with the North Cascades” by no less an authority than historian Harry Majors it seems likely that Lage’s obscurity is due, in large part, to both his self-effacing nature and the fact that he never perceived himself as doing anything other than carrying out the basic responsibilities of his job. Yet, during the thirty-five years he worked throughout the Pacific Northwest and Alaska for the Forest Service (1908 to 1943) not only did Lage deliver landmark work as a photographer, surveyor and cartographer but he also made the first ascents of over 77 Cascade peaks and, in the process, became a sought-after expert in fields as diverse as photogrammetry, silviculture, geography, botany, horsepacking and parachute-assisted firefighting. Born to a prominent family in Strengnas, Sweden, on May 3, 1878, Lage was one of seven boys, all of whom, with the exception of Lage, became officers in the Swedish military. Preferring to chart his own course Lage, instead, attended the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm where he graduated at age 19 in 1897. After working for a year as a draftsman Lage immigrated to the United States and completed a master’s degree in Forestry at Yale University in 1903. Like many Yale graduates of the era it is likely he was profoundly influenced by the writings of Gifford Pinchot and quickly moved west to Portland, Oregon, where, in 1908, he found a job with the United States Forest Service.  A numbered Wernstedt photograph entitled “Blackcap SSE” shows a portion of the Pasayten Wilderness near Eureka Creek, northeast of Slate Peak. A crew member sits in the rocks near the center of the image. (Click for closeup) A numbered Wernstedt photograph entitled “Blackcap SSE” shows a portion of the Pasayten Wilderness near Eureka Creek, northeast of Slate Peak. A crew member sits in the rocks near the center of the image. (Click for closeup)Writing to the Yale Alumni bulletin in 1913 Lage stated that “I have been lately involved in making topographic maps.” A declaration that both captures his gift for understatement and presages the next decade during which he would photograph and map large tracts of Oregon, the western Cascades and coastal Alaska. It was not, however, until the mid-1920’s when he found himself assigned to the Winthrop Ranger District that Lage’s most prolific period as both a surveyor and explorer began. Charged with mapping the mountains north and west of the Methow he would lead a string of pack horses into the mountains each spring and, by following Indian trade routes and miner’s trails, establish himself in the general vicinity of the peaks he wished to survey. From there he would proceed on foot, sometimes in the company of other Forest Service employees and sometimes alone; but always dressed in the same cork boots and cowboy hat, carrying a frameless canvas pack jammed with supplies including a daunting array of surveying tools, witness plaques, 8” x 10” camera plates and whatever other recording instruments he felt his work might require. Over his shoulders he would carry his surveying instruments and camera tripod and, for more technical ascents, a home-made alpenstock and a few meters of hemp rope. His early work concentrated mostly in the Ross Lake area where he made the first ascent of Desolation Peak and later named Mount Despair. Shortly thereafter, however, his focus shifted to the Pasayten and what is today the US Route 20 corridor and during the ten year period that followed (1926 to 1936) his efforts produced an astonishing wealth of topographic data, based largely on the perspectives he was able to gain by climbing to the summits of the region’s highest peaks. Among the scores of first ascents he made at this time are Cascade luminaries such as Logan, Black, Silver Star and North Gardner and, in the Pasayten district, Lago, Osceola, Carru, Blackcap, Lost, West Craggy, Big Craggy, Ptarmigan, Lake and Azurite— all of which rank among the state’s 100 loftiest peaks. Yet, as John Scurlock, the reknowned photographer, has pointed out, part of what makes Wernstedt so remarkable is that his only comments regarding these ascents appear as footnotes to the maps he was creating for his employers. “He wasn’t there as an alpinist,” Scurlock explains, “he was there as a surveyor and photographer . . . carrying out his duty to the agency.”

John Roper, a prolific first ascensionist in his own right, recalls climbing Mount Benzarino in 1976 and assuming that because he found no cairn on top that Wernstedt may not have actually reached the summit. A claim dispelled only a short while later when Harry Majors discovered the panoramic photograph Lage had taken from the top. Benzarino, as Roper points out, also provides an excellent example of Wernstedt’s status as a “unique name-bestower.” According to legend, he named the peak after a Basque sheepherder he met at its base. Friends and family members were the source of other place names and Mount Barney is said to have been named after his favorite horse. Only Mount Lago, a play on way Americans pronounced his name, commemorates the man himself.

As the 1930’s waned, and what John Scurlock refers to as the “romantic era of forestry” came to an end, Wernstedt began spending less time in the mountains and devoted more of his energies creating an aerial stereoscopic camera that would produce more accurate contour maps and, in 1940, partnering with David P. Godwin and Harold King to initiate “a parachute jumping experiment” based out of Winthrop and aimed at delivering highly trained firefighters to conflagrations deep in the wilderness. With those tasks complete, Lage retired from the Forest Service in 1941 and moved with his wife to, first, Waldron Island and, later, to Guemes Island where he died in 1959 at the age of 81. Since that time collections of his photographic plates have shown up in museums, private collections and at several Forest Service stations including the Winthrop District. Apt reminders, for those who have seen them, of a time before aircraft-based high resolution digital photography when mapping these lands was the work of giants. 7/11/2013 Comments Nice article, Geof! Jim Archambeault Twisp Thank you so much for writing this. Lage is my great grandfather on my grandmother's side. Doris (Doe), his daughter was my grandmother. our family is rich in history, mostly because there is so much out there about June and Farrar Burn. But sadly, while most of us know a bit about Lage, it's not nearly as developed. I was able to see photos and hear someone else's knowledge. And for that, I'm very grateful. thank you. Finn. Finnian Farrar Burn

|