|

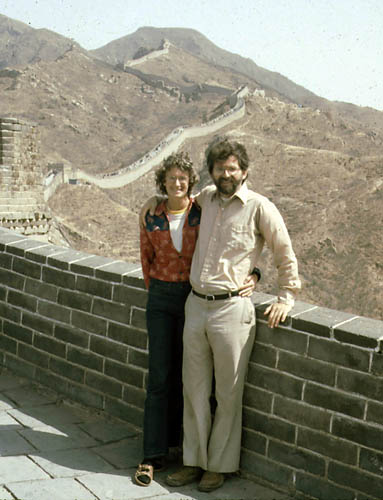

Diana Hottell on the Great Wall of China. What was

the most foreign place I’ve ever visited? One of them was the “hutongs,” the back-street

neighborhoods of Beijing.

In Hong Kong Diana and I were crammed

into a tiny, closet-size room in a hotel on the fourteenth

floor of a high-rise. That is, the entire hotel occupied

only a part of the fourteenth floor. One room had been sub-divided

into nine tiny cubicles separated only by flimsy, head-high

partition screens. Presto! The one room had now become a

nine room hotel, the Lee Garden Guest House! In this sardine

can of a hotel, in 1983, another traveler told us the astonishing

news that Communist China had just opened up a number of

cities to foreign tour groups for the first time.

It

took three train rides to get from Hong Kong to Beijing,

the last one lasting 48 hours.

We then

managed the nearly impossible task of obtaining visas for

solo travelers (with no tour group) for China, caught a

train up to Hong Kong’s Northern Territory, walked across

the chaotic, crowded border, caught another train for Guangzhou

(formerly Canton), and spent the next forty-eight hours

on a passenger train to Beijing. The endless rail journey

crossed both of China’s great rivers, the Yangtze and the

Huang Ho (Yellow River), and passed hundreds of miles of

bright yellow fields of rape seed. Early in the morning

the passengers were abruptly awakened by Mao’s revolutionary

martial music. It blasted through scratchy loudspeakers,

shattered the night-time silence, and shattered the nerves

of all passengers. The “music” continued all day.

The most

interesting person I met on the train was a 33 year-old

man dressed in a Chinese army uniform with a red star on

the cap. Xiu Xiao Dung spoke halting English, but was able

to describe his teen-age years when he served as a member

of Mao’s Red Guard and helped to smash and destroy ancient

artworks as well as other reminders of China’s pre-Communist

past. Xiu and the Red Guard were also assigned to monitor

and police any un-Communist behavior wherever he might find

it. He was given the authority to search out teachers, merchants,

laborers, anybody who might be guilty of wrong-thinking,

guilty of ideological error. But now Xiu was an engineer

with the army and he felt extremely lucky to be able to

travel to a trade fair in Guangzhou. His first such trip.

When Xiu learned what Diana and I were doing, traveling

alone for thirteen months, he jerked in shock and quickly

leaned over to tell his colleague who also blanched in disbelief.

Given the salaries in China, there was no one in the country,

including top politburo members, who had the money or the

freedom of travel to do what we two were now doing. I felt

indescribably grateful at that moment. I felt like one of

the elect. I have been blessed by fate. Our year-long trip

was a total impossibility to all the one billion people

in Communist China.

The lengthy train ride ended with the

customary early-morning blast of revolutionary martial music

and we rolled into Beijing.

The train arrived in China’s

great capital city at 7:00 am, just in time to meet the

swarm of morning rush-hour foot traffic. In the gigantic

Beijing Railway Station I walked into the men’s bathroom

and was surprised to see the Chinese version of a group

toilet. It was a long, white-tiled trench latrine which

men had to straddle in order to defecate. Like the other

men, I dropped my trousers, spread my feet across the trench

and squatted. But then I was startled to see half a dozen

Chinese men stop and stare blatantly at my genitals. Their

faces showed no trace of embarrassment or modesty, just

open curiosity. Or perhaps I was the first westerner they

had seen in fifty years.

Bill

and Diana managed the nearly impossible task of obtaining

solo traveler visas for China in 1983. The most interesting sight for

me was an ancient Chinese apothecary shop – the neighborhood

drug store – in one of the hutongs of Beijing. This city

of nine million (in 1983) is actually a vast collection

of villages crammed together. The “village” is called a

“hutong,” and is divided off from others by a tall wooden

entrance, an ornamental gateway. Unfortunately, the Chinese

government decided to upgrade sections of Beijing by destroying

some of the hutongs, and later rapidly accelerated the bull-dozing

of ancient neighborhoods in order to “modernize” the city

before the Olympic games of 2008. The government has thus

committed a terrible act of vandalism by destroying much

of the early Chinese architecture, culture and the old way

of life.

In any case, Diana and I were privileged to stay

in one of the ancient hutongs in 1983. I walked into a venerable

old apothecary shop, sat down and started looking over the

thousands of large glass jars that lined the walls up to

the high ceiling. I wish I had written down some of the

contents, but there were jars filled with herbs, leaves,

stems, flower blossoms, bark, plants of all types, medicinal

plants with healing characteristics; large jars with deer

horns, jars with large bones, jars with small bones, jars

with bird wings, jars with bird nests, jars with bird beaks,

jars with bird feet, jars with snake skin, jars with dried

reptile parts, jars with dried lizards, jars with dried

sea horses.

A customer would walk in and discuss his ailment

with the druggist who stood behind the two hundred year

old counter. Then the druggist would gather specimens from

several different jars, pick up his butcher knife, chop

them rapidly into a powdery form and pour it into a container

for the contented patient to carry away.

I felt that I had

just gone back in time to another century, to an old China

and an ancient way of life that was very, very foreign to

me.

Here in the Far East, here in a mysterious old apothecary

shop in Beijing I took time to thank my boyhood hero, Tom

Sawyer, for having pointed me toward a lifetime of seeking

adventure.

Spring 1983

|

|