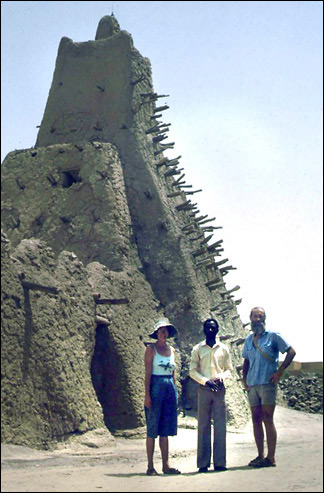

Diana Hottell, Bob Jones and (center) a political

dissident exiled to Timbuktu stand in front of a 14th century mud mosque, part of the University of Timbuktu. The high school teacher-dissident was exiled for two years to Timbuktu. Some dissidents were sent to even more remote places—to the sale mines north of Timbuktu.Every

morning I woke up covered with desert sand over my sleeping

bag, with Sahara sand in my ears, in my mouth and in my

nostrils. Then Al Khamis (whom I looked on as “Huckleberry

Finn of Timbuktu”) would go on his morning rounds to bring

us water which we boiled on the little blue gas stove.

Then we began the routine of gulping water that was still

too hot to drink. Several times I singed my mouth on the

scalding hot water, but immediately started boiling up

another pot. It seemed like we spent all morning just

boiling enough water.

The drinking water on the Niger riverboat had been truly

foul. Each dinner table had four quart bottles of water,

but the water was drawn directly from the Niger, sometimes

where raw sewage had been dumped directly into the river.

So I noticed upon closer inspection that the “drinking

water” contained small chunks of solid matter, possibly

chunks of human feces. Thus I learned to boil the water

every morning up on our rooftop home in Timbuktu.

We had arrived at Timbuktu in the seventh or eighth year

of a famine. So many cattle and people had died from the

drought in the southern Sahara that about 15,000 desert

refugees had moved into reed shelters around the town

and doubled the population of Timbuktu. Since the famine

was still in effect, there was very little food available

in the open-air markets except a few onions, tuberous

roots and bullion cubes. We could buy piping hot bread

at a couple of street-corner ovens. A woman would pull

the round and flat loaves of bread from the fire-heated

beehive oven and quickly fling them onto the ground which

was entirely sand. They were too hot to handle. We could

buy warm bread a minute later, but all the loaves were

covered in a generous layer of sand. If fact, all the

food in Timbuktu contained windblown sand. Every time

we ate a meal we chewed on sand along with the food. I

didn’t realize the effect until we returned home to Twisp

a year later and I sat in the dentist’s chair. When I

opened my mouth the dentist cried in alarm, ”What in the

world have you been chewing on? Your gold crowns are pitted

like the craters of the moon!”

In the glory days of Timbuktu in the 14th and 15th centuries

the city stood on the banks of the great river, but today

the Niger has changed course and moved four miles to the

south. So the night we departed Timbuktu we were ferried

in a long dugout canoe along a marshy canal for four miles

through the blackest midnight. The African boatman skillfully

guided the dugout through the darkness where the only

sound that broke the silence was the slight swish of his

long pole in the water.

The boatman dropped us at the Niger landing where the

riverboat would be arriving. But nobody knew what time.

Probably sometime tonight. There is a great joke played

on outsiders who visit West Africa. The riverboats do

have printed timetables, but the official schedule bears

no relationship whatsoever to the actual arrival times

of the boats. For example, when we had first begun the

Niger adventure and boarded the riverboat near Bamako,

the vessel was eighteen hours late in starting. And that

was at the beginning of the voyage! Early in the trip

the boat got stuck on a sandbar where all passengers had

to be off-loaded into dugout canoes and taken to the nearest

village. This was a mere twelve hour delay in the “schedule.”

Meanwhile, I was sitting in the dark beside the river

when a Sahara sandstorm blew in. The winds were blowing

so fiercely that the entire contents of my shirt pockets

were blown away – I never found a trace of them – including

the priceless little notebook of my diary jottings. So

I just wrapped my turban tightly around my face and head,

squeezed my eyes closed and lay down in the desert sand

to get away from the whirling wind and sand. I busrrowed

deep into the sand and pulled into the fetal position.

I felt exactly like a helpless baby as the howling winds

blew the Sahara sands. Sand blew into my eyes and scratched

the right eyeball so badly that the eye would not heal

for several days.

The riverboat finally arrived for us sometime before

sunrise, but during that blackest night of my life in

the swirling sandstorm I had several hours to realize

just how far off the beaten track I had journeyed. Mark

Twain’s fictional character had inspired me to seek out

fabled Timbuktu here at the end of the world in the Sahara

Desert. |