|

Forest Ecologist: Peter Morrison

story by Solveig Torvik

Peter Morrison’s work first came to prominent public attention, and kicked off a career-change, in the 1980s, when he was a seasonal employee of the U.S. Forest Service in Twisp.

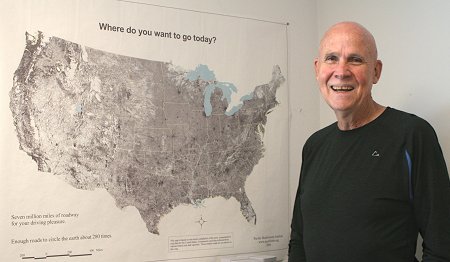

Peter Morrison, executive director of the Pacific Biodiversity Institute in Winthrop, mapped the roadless areas of the United States. - Photo by Solveig Torvik

This was back when battles still raged about the survival of both the old growth-forest dependent Northern spotted owl and the timber industry. When not on the government’s payroll, Morrison worked as a consultant for the Wilderness Society. And in that capacity, he used the Forest Service’s own data, plus aerial photos, to map - and thus try to settle - the argument about how much old growth really was left in the Northwest woods.

His startling findings were widely reported. Trouble was, Morrison discovered that the amount left was drastically less than Forest Service officials had been claiming. “It affected my career,” Morrison recalls. The head of the agency, Dale Robertson, was not amused, and Morrison was called in by his superiors in Twisp, who “chewed me out a lot. I was told I was never to do anything like that again.”

But he did. And, as head of the Pacific Biodiversity Institute in Winthrop, he’s still doing it - on an even grander scale.

“I wasn’t trying to make the Forest Service look bad,” says Morrison. “I was just reporting the facts.” The upshot was that he was offered a full-time job with the Wilderness Society that paid four times what he’d been making with the Forest Service.

Morrison, 61, was hardly a novice at ecological mapping and analysis when the old growth controversy occurred. His first effort, in 1972, had been an ecological survey and mapping of what became Idaho’s Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness while working for the Sierra Club, and he wrote the original report proposing it become a wilderness. “We asked for 2.4 million acres. We got 2.3 million,” he says. “It’s the single largest wilderness outside Alaska.”

He grew up in Colorado, where both his parents were geologists. He attended Haverford College in Pennsylvania, received his bachelor’s degree in biology and forest management practices from the University of Oregon and holds a master’s degree in forest ecology from the University of Washington. With his wife, Aileen Jeffries, who has a master’s degree in physics, he moved to the Methow in 1975. “We didn’t come with the idea of doing science,” he recalls. They just wanted to live in the rural west. “We liked what we saw,” he explains.

They bought 80 acres on the West Chewuck and tried farming but soon discovered they couldn’t make a living. So they started an alternative energy business installing solar panels. “We put in the first solar electric systems in the valley,” he says. In 1982 he decided to get his master’s degree in forest ecology. This eventually led to a stint working for the Sierra Biodiversity Institute in California, and in 1994 he and his wife moved back to start the Methow Research Station, affiliated with that institute. In 1998, Morrison established the Pacific Biodiversity Institute as an independent non-profit organization.

Depending on the season, the institute has up to seven part-time employees. Typically it works on contract for agencies such as state parks departments in Oregon and Washington, public utility districts and federal agencies, as well as conservation organizations such as the Sierra Club and Conservation Northwest. His organization makes use of volunteers to help get the work done. “A lot of people want to get involved. We’ve been trying to make the most of that,” he says. In addition, the institute offers internships to college students.

Among the institute’s recent local projects was mapping the whereabouts of the Western gray squirrel, which the state of Washington, but not the federal government, has listed as a threatened species. “It’s not a charismatic creature,” Morrison says of the squirrel. Nonetheless, 30 local volunteers have spent time tracking its habits and movements over the last two-and-a- half years, and Morrison has produced a report and created a map that pinpoints all the locations in the upper Methow Valley where it has been observed.

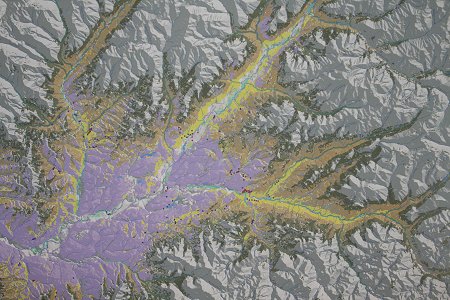

The red dots on this Pacific Biodiversity Institute map document where the Western gray squirrel has been found in the upper Methow Valley. - Photo by Solveig Torvik

He has worked on a wide variety of conservation issues – the relationship between fire and forest management, the Loomis Forest campaign, salmon habitat assessment in Puget Sound and the Upper Columbia Basin, rare plant surveys, Puget Sound harbor seal distribution, watershed analysis. His mapping work correlated the distribution of old-growth redwoods with marble murrelet sightings in Northern California and led to a U.S. Supreme Court decision that increased protection for both species.

A botanist and forest ecologist, he’s an expert in remote GIS sensing techniques. Among his signal achievements is mapping, at the behest of the Pew Charitable Trust’s Campaign for America’s Wilderness, the remaining roadless areas in the entire United States, including Alaska, Hawaii and Puerto Rico. It shows that the nation’s existing roads would circle the earth 280 times.

Recently Morrison has taken on the mother of all ecological inventory and mapping projects: the continent of South America. “For much of the rest of my life I want to work on what we call The Big Wild,” he explains.

In the United States, he notes, “We’re protecting these little, itty bitty scraps.” But in South America it’s a markedly different story. “The conservation opportunities that are present in South America are immense, way beyond anything we have here,” Morrison says. In just Chile and Argentina, where he’s been working, on foot, ground-truthing the landscape and documenting what’s on it with GPS-enabled cameras, there are 30 wildernesses of more than 2.4 million acres.

Why South America? “It’s the lungs of the planet,” Morrison says. “It’s important to all life on Earth. This is the place where biodiversity makes its maximum expression, biota maxima,” as he calls it. “It’s vitally important to the climate of the planet. If you look at global conservation priorities, South America is just critical.”

The good news is that even though some parts of the continent are being ravaged by mining, logging, slash-and-burn farming, its wilderness is so huge that there’s still time to avoid a planetary disaster, he says. At the current rate of destruction, it will take 200 years to completely destroy it, according to Morrison.

The institute initiated this daunting conservation challenge with its own funding, he says. He’s working not only with local conservation and education entities in South America but is also trying to persuade U.S. environmental organizations to support this conservation effort, which he argues will benefit humans everywhere on the planet.

“Some of these areas ought to be made into national parks, bi-national or tri-national parks,” Morrison says. “But only the people who live there can make it happen.”

04/10/12

|