|

A view of the Stokes ranch, east of Twisp. A view of the Stokes ranch, east of Twisp.

Complex and Labor-Intensive

Stokes family ranch

story and photos by Solveig Torvik

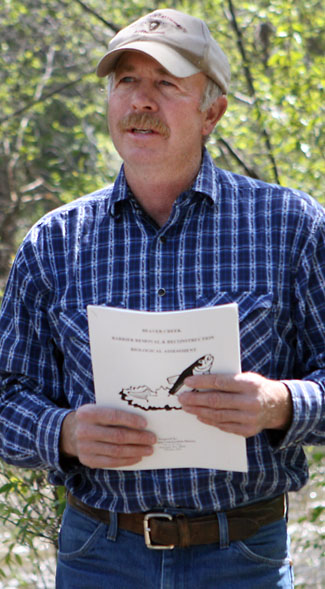

Rancher Vic Stokes explains the challenges of ranching along Beaver Creek. Rancher Vic Stokes explains the challenges of ranching along Beaver Creek.

Vic Stokes belongs to the fourth generation of a family that has tried to wrest a living off the land in the Methow Valley. He and his family run a cow-calf operation off Highway 20 east of Twisp on land that’s been in the family almost continuously since his grandparents bought it in1921. His great-grandfather, would-be miner James Stokes, first showed up here from Chicago in the 1890s.

The incoming president of the Washington Cattlemen’s Association, Stokes, 57, raises 175 to 200 head of cattle on 1,600 acres. “It’s what the family can manage,” he explained last weekend to a Methow Conservancy group that came to learn what it’s like to be a rancher trying to work his land in the Methow these days. With his wife Carrie, a teacher, son Kent and his wife Amber, as well as son Blake and his wife Abby living on the farm, the Stokes are carrying on what their ancestors started here generations ago.

Vic Stokes, a member of the Methow Conservancy board, has been a leader in trying to find efficient ways to ranch “holistically.” Even so, he has his reservations. “I hate to see all the means of production taken away from us,” he told the Conservancy group. In 2002, the Stokes ranch was the first in Eastern Washington to be placed into a U.S. Department of Agriculture-sponsored conservation easement. “We locked in a future for this land to be ranched,” he told Grist.

The family’s cow-calf ranching operation is one of a half a dozen left in the valley, according to Stokes. Beaver Creek runs through their property. From the 1940s to the 1960s, there were as many as 1,000 head of cattle being raised along that creek’s drainage, he said. Now there are 600. “It takes a lot of effort to keep a ranch going,” said Stokes.

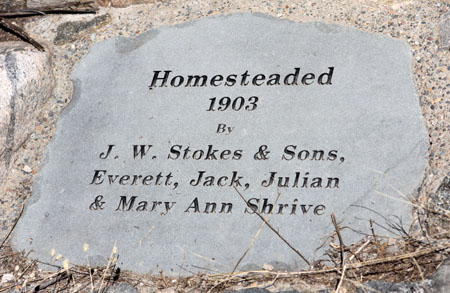

The Stokes family’s ranching history is deeply embedded in the land that reaches up toward the rolling hills northeast of the current ranch. On a hillside with sweeping valley views is a plaque marking the establishment of the first Stokes homestead in 1903 by his grandparents, Jack and Anna Shrive Stokes. Both sides of that family amassed dryland acreage on those hillsides that long ago was sold to the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Jack and Anna eventually moved down to today’s ranch but they lost it during the Depression. In 1945, Vic’s parents Jay and Elsie bought it back and moved back in. So it’s fair to say the Stokes

family is well schooled in the vicissitudes inherent in making a living off the valley’s soil.

“It takes a lot of feed to get cattle through the winter. You have to know how to raise crops,” Stokes explained to the group. “And it has to be sustainable.” Healthy riparian areas adjoining rivers and streams are an important component of sustainability, he added.

This plaque marks the 1903 dryland homestead of Vic Stokes' grandparents east of Twisp.

First and foremost is water. He farms ground that has both good and poor water rights, Stokes explained. The water rights on Beaver Creek were the seventh to be adjudicated after the state began assigning water rights in 1917, he said. So the “first in time, first in right” water right principle was thought to have settled troublesome water issues until the wild salmon were listed under the Endangered Species Act in the 1990s. Suddenly ranchers on Beaver Creek were being told they had to improve fish passage past irrigation diversion dams and to screen water pipes in ditches.

“It kind of irritated me,” Stokes confessed, because “Nobody talked to me about this…They made it sound like a bomb had been dropped in here.” Stokes said he had been unaware that fish screens were required. He got his neighbors and the numerous state and federal agencies that were involved to sit down at the same table to try to improve communication. “Don’t mess with our water rights” was the bottom line for the ranchers. Eventually they worked out cost-sharing agreements to fund required improvements.

The over-arching challenge was to have healthy riparian areas for fish and still maintain water rights, Stokes said. That challenge may have been met. “Steelhead have made it to the Beaver Creek campground,” he said, adding that “the whale culvert” on Highway 153 has been the biggest improvement in improving fish passage. “I hope there’s a check by a box somewhere that says Beaver Creek is not as bad as it was,” he told the group.

The Stokes ranch became much richer in riparian area in the wake of the 1948 flood that washed out all of the valley’s bridges. About five or six acres that used to be pasture were inundated, and today it’s hard to envision that pastureland existed where a crowded mixture of tall cottonwoods, alder, aspen and birch trees reach for the sky from boggy soil and serviceberry bushes and willows line the creek.

This riparian area on the Stokes ranch was a pasture before the flood of 1948. This riparian area on the Stokes ranch was a pasture before the flood of 1948.

His cows have been moved away from the creek to prevent degradation of water quality. “I personally don’t see a lot of problem with grazing riparian areas,” Stokes said. “Riparian areas are very resilient.” But he cautioned that it would have to be for short periods only and with a limited number of cattle. “If you had 200 head of cattle in here for six months, this place would look pretty tough. It’s kind of common sense.”

Stokes grazes his cattle on Forest Service land as well as on 25 to 30 old homesteads, many of them now owned by the state. He raises alfalfa and hay for winter feed on his own land. Harvesting is done by tractors costing $60,000 to $80,000 each. Using it means he alone can pick up 100 tons of hay a day.

He uses rest and rotation to keep his fields healthy. “I’m not much of one to go out here and do a lot of spraying,” he said. For one thing, he doesn’t think it’s particularly effective.

“We make money from cattle,” said Stokes. “We’re production oriented.” So cows are expected to “pay their way.” This harsh arithmetic means: produce offspring or die. “If they don’t have a calf in them when they come in (off the range), they have to go down,” he said.

Stokes is looking for cows that produce calves with a birth weight of about 70 pounds. It takes two years before a cow can give birth to the first calf, then it has to be fed nearly a year before it can be sold. Born in January and February, calves are auctioned off in late fall at about 600 pounds, usually in Davenport. “We do not finish our cattle,” Stokes said. The oldest cow on the place is 16, but her teeth are going, so this is her last year of calf production, according to Stokes. Typically ranchers expect their cows to be bred for about 10 years.

Among many other things in this complex, labor-intensive endeavor, Stokes has to worry about silver, copper, iodine and nitrates in the soil. Under certain circumstances cattle can get nitrate poisoning from hay, for example. “Their blood turns blue. They suffocate, and it’s rapid, sometimes within minutes,” he said. He uses antibiotics sparingly; of the last 175 calves born, seven got antibiotics. “We use a lot of preventive vaccine,” as many as 10 or 11 different ones, he added. Cows get one annual vaccination.

“Bulls are set up for trauma” during impregnation of cows, Stokes said, including the risk of broken penises. So he inseminates many of his cows artificially, a delicate operation during which he inserts 10 to 12 million sperm encased in a long “French straw” into the cow. This is 80 percent successful, he said, the same rate as using the bulls. Each straw he buys costs about $25, but the price can be hundreds of dollars for semen from prize bulls.

Ranchers tend to be ``asset rich but just getting by,’’ Stokes notes. “In the long run, it still has to be a business.” So is he hopeful about the future of ranching for his family?

“I’m always a pessimistic optimist,” he laughs. Because of the conservation easement, the soil he owns will always remain available to grow food, even if it’s not meat. “People will always need something to eat.” And they’ll always need healthy soil to grow it on.

5/9/2012

|