home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

Spring Chinook ready to have their eggs removed at the Winthrop National Fish Hatchery, one of two hatcheries here. Spring Chinook ready to have their eggs removed at the Winthrop National Fish Hatchery, one of two hatcheries here.An expensive table is being set in the Methow Valley in hopes that the dinner guests eventually will show up. More than $269.1 million has been spent in the Methow Valley over recent decades to entice these elusive guests to the table. We’re talking about salmon, of course. Flipping on a light switch in the hydro-powered Pacific Northwest means flipping off salmon. So it follows that it’s electric ratepayers who bear much of the salmon restoration burden, though taxpayers contribute significant sums. Local contributions, user fees and private donations also make their way into the mix. The Methow Valley’s piece of the Northwest’s multi-billion-dollar salmon restoration experiment is a microcosm of this large-scale, unprecedented attempt to restore a wild species. It offers an illuminating, close-up look at what it takes to undo a century of eco-system damage. The money spent in the Methow is being used to lure endangered, naturally spawning wild spring Chinook salmon as well as threatened summer steelhead and bull trout back to the Methow, and to raise designer fish in local hatcheries. Where 16 million salmon once thrived in the pre-dammed Columbia Basin, today only one million do. In the 1860s, biologists say, an estimated 64,000 salmon—24,000 spring and summer Chinook (King), 36,000 coho (silver) and 3,600 steelhead (seagoing trout)—existed in the Methow river system. It's a good year when 5,500 naturally spawning salmon and steelhead show up

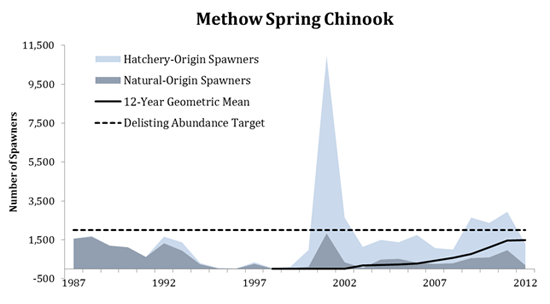

Today, it’s a good year when 5,500 naturally spawning salmon and steelhead show up in the Methow, as they did in 2010. Two to four times more of returning salmon typically are hatchery fish rather than natural spawners, according to Greer Maier, science program manager for the Upper Columbia Salmon Recovery Board (UCSRB). Hatchery fish are released from the Methow Basin by the hundreds of thousands. But government biologists argue that they are genetically inferior to wild fish and prone to disease. They also say hatchery fish crowd out wild fish, a contention that tribal hatchery proponents and others dispute. The upshot is that the wild salmon revival experiment and hatchery production run in parallel, and perhaps in conflict, on the same turf.  Derek Van Marter, executive director of the Upper Columbia Salmon Recovery Board Derek Van Marter, executive director of the Upper Columbia Salmon Recovery BoardMethow salmon enter the Columbia River at Pateros and travel the 424 miles to sea and back past nine dams—if they’re lucky. In 2002, for example, said Maier, 7,585 spring Chinook passed over Wells Dam headed for the Methow River but only 2,637 made it home to their spawning ground. “We have a very high pre-spawn mortality rate,” she added, due to harvest and poor habitat conditions. “Steelhead are responding. Spring Chinook are not yet responding,” said Derek Van Marter, executive director of the UCSRB, which funnels funds to organizations that are restoring salmon. A dogged effort is under way to get at least 2,000 naturally-spawning spring Chinook and 2,000 steelhead back to spawn each year over a 12-year period. When that happens—and some additional criteria are met—the Methow will have sustainable populations of these wild fish, according to scientists. In 2006, a 30-year clock was set for reaching that recovery goal for salmon and steelhead. There is as yet no recovery plan for bull trout. The two drivers of salmon restoration are the 1973 Endangered Species Act and the 19th Century treaties signed by the United States with sovereign Indian nations that reserved their historic rights to harvest salmon. The bible that governs salmon recovery is the Biological Opinion of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It states that fish survival depends on water quality and quantity, cover and shelter, food, riparian vegetation, space, safe passage and access. This is a nice way of saying that the infamous “four H’s”—hydropower, harvest, habitat and hatcheries—all have played a role in destroying wild salmon runs. The four H's have all played a role in destroying wild salmon runs

Salmon restoration in the Methow focuses on habitat fixes and getting water back into streams and rivers. Along with improved hatchery production, they are the low-hanging fruits of salmon restoration because they are politically feasible. But dismantling dams, which provide electricity and flood control, and reducing salmon harvests? Not so much. Production of hatchery-raised fish has been under way in the Methow for almost 74 years. But local habitat restoration projects got seriously under way more recently. Heavy equipment has been rolled into rivers to deposit woody debris and logs and to reroute channels. Miles of fencing has been built along riverbanks to keep cattle out of rivers, and miles of plastic irrigation pipes have been installed to move irrigation water downstream more efficiently. More large-scale habitat remodeling is on the way: This year, the Yakama Nation plans to dig out and restore 4,500 feet of an old side channel to the Methow River in Twisp for use by juvenile salmon.

Among the ongoing local habitat projects is a fish spawning refuge created below Hancock Spring in what once was a trampled-down, shallow stream below an old Mazama dairy. First, the stream bed was laboriously dug out by hand. The broken-down stream banks were rebuilt. Hundreds of small logs were added to the stream bed, which was replanted with thousands of tiny plugs of insect-friendly or shady native plants. Overseeing this work is John Jorgensen, a Yakama fish biologist. He worries that the Methow River lacks nutrients because it has long been deprived of the masses of decaying salmon carcasses needed to keep river ecosystems fish-friendly. He will add nutrients to the stream to see if that helps. Every endangered or threatened fish species has shown up to spawn

The one-mile long stream is divided into two reaches, one untreated, the other improved. It’s a natural scientific laboratory where Jorgensen over time hopes to test what salmon need to spawn here and get high numbers of their offspring to sea. Salmon science is maddeningly time-consuming, thanks to their four-year migration cycle. Since completion of the first restoration phase in 2011, a sprinkling of every endangered or threatened fish species in the Upper Columbia basin has shown up to spawn in the newly rehabilitated stream, said Jorgensen. The salmon much prefer the restored reach; they built 18 redds in it compared with just one in the unrestored reach, for example. But it’s non-native brook trout that are most common in this stream, and they snack on salmon eggs. So they will be removed to see if that helps salmon survival, he said. “Rebuild it and they will come,” is the mantra that’s driving the transformation of the Methow Valley’s riverine ecosystem. THE COSTS  BPA markets and distributes wholesale power to utilities such as Winthrop's Okanogan County Electric Cooperative. Much of the salmon recovery funding has come from BPA ratepayers. BPA photo BPA markets and distributes wholesale power to utilities such as Winthrop's Okanogan County Electric Cooperative. Much of the salmon recovery funding has come from BPA ratepayers. BPA photoThe 1,000-pound gorilla in the Upper Columbia salmon recovery funding mix is the Portland-based Bonneville Power Administration (BPA). BPA markets power produced by 31 dams operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers or U.S. Bureau of Reclamation throughout the massive Columbia River drainage. BPA wheels the electricity over 15,000 miles of transmission lines to wholesale customers in eight western states, including utilities such as Winthrop’s Okanogan County Electric Cooperative. Though its salmon recovery efforts began in 1978, the BPA cannot provide records of salmon expenditures in the Methow prior to 2004 because its previous accounting system did not reveal that level of local detail, BPA spokesman Kevin M. Wingert told Methow Grist. This accounting black hole means the $269.1 million spending estimate likely is too conservative, since it does not represent any funds that may have been spent by BPA in the valley in the 26-year-period between 1978 and 2004. Moreover, hatchery work has been ongoing in Winthrop since1940, but the costs represented here account only for spending during the last 11 years. Also missing from the tally are federal taxpayer funds spent on salmon habitat in the Methow before 1999. The truth is that no one knows how much has been spent restoring salmon to the Methow. However, the numbers that are available help capture the extent of the effort. At the present rate of spending, the day is not far off when it will reach the $300 million mark—if it hasn’t already. The $269.1 million spending estimate

likely is too conservative Since 2004, BPA has doled out $183.2 million total for Methow salmon recovery, to eight major partners that perform, or contract out, the hands-on work. Of that sum, $3.4 million was spent on capital expenditures, according to BPA spokesman Wingert. In addition, $21.6 million has come to the valley since 1999 from the State of Washington’s Salmon Recovery Funding Board/Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO). It distributes salmon restoration funds from state, federal and local sources—but not from the BPA or the PUDs—to regional boards such as the Upper Columbia Salmon Recovery Board, the umbrella organization that then passes on the RCO funds to salmon-restoration entities in the five sub-basins in the Upper Columbia region. That board’s members are county commissioners from Chelan, Douglas and Okanogan counties and representatives from the Confederated Tribes of the Yakama Nation and Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. These regional boards wrote the federally mandated wild salmon recovery plans and they are now implementing those plans. The RCO has distributed grants to projects in the Methow Valley some 60 times since 1999, RCO records show. The RCO requires a 15 percent matching fund from grant applicants. That added approximately $5.1 million more in expenditures here, according to RCO documents. Some, but not all, of those funds came from PUDs or other sources that already may have been accounted for elsewhere. To avoid counting the same funds twice, the $5.1 million in matching funds are not added to the RCO’s $21.6 million contribution. HATCHERIES  U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Matt Hall with a spring Chinook that made it home to the Winthrop National Fish Hatchery U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Matt Hall with a spring Chinook that made it home to the Winthrop National Fish HatcheryThere are two fish hatcheries in the Methow Valley, both in Winthrop. Hatchery operators generally try to supplement wild runs with hatchery fish that are as genetically close as possible to the ones that originally evolved to live here. The hatcheries traffic in fish that are designed to meet the demands of sport, tribal and commercial fisheries, which are major economic and political drivers of salmon policy. Combined, the two hatcheries annually raise and release more than a million baby salmon, called smolts. The Winthrop National Fish Hatchery off Twin Lakes Road was built in 1940 to mitigate the effects of Grand Coulee Dam on fish runs. It’s operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service with federal tax funds bicycled over from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and with ratepayer funds from the BPA. It has six permanent full-time employees, one part-time, and an annual operating budget in 2013 of $932,000. It produces 950,000 smolts annually, including 250,000 coho produced for the Yakama Nation with BPA funds, all at a total cost of about $1 per fish, according to hatchery project leader Chris R. Pasley. In the last 11 years alone, a total of $6.8 million was spent to operate this federal hatchery, excluding the BPA funds (accounted for elsewhere) that paid for Yakama operations there, according to Pasley. During the last five years, releases from the federal hatchery of spring Chinook smolts ranged from 372,000 to 590,000. Between 750 and 3,800 returned as adults to be counted at Wells Dam, Pasely said. During the same period, 100,000 to 121,000 summer steelhead smolts were released, and between 450 and 1,300 returned. The highest adult return over the last

10 years was 5,796 coho The federal hatchery plans to reduce production of spring Chinook “since too many hatchery fish on the spawning grounds is considered a risk to the natural-origin spring Chinook population,” said Pasley. That will be done by transferring production of 200,000 smolts to the Okanogan River Basin, he said. The Yakama release 350,000 smolts annually from the Winthrop federal hatchery and tribal acclimation ponds in the valley, according to Yakama fish biologist Rick Alford. Counted at Wells Dam, the highest adult return of the tribe’s smolts over the last 10 years was 5,796 coho in 2011, he said. In 2016, as the federal hatchery moves its production of spring Chinook out of the Methow, the tribe plans to increase its releases from the Methow basin to a total of 1 million coho smolts, according to Alford. The Yakama, headquartered in Toppenish, don’t harvest fish in the Methow watershed but depend on homeward-bound Methow fish runs as part of their treaty rights to harvest salmon on the Columbia River. The Yakama Nation keeps three offices in the Methow Valley for 12 to 15 permanent employees as well as half-a-dozen seasonal technicians who carry out its hatchery and habitat-related projects here, according to Jorgensen. All told, the Yakama have been awarded $39 million in ratepayer funds for salmon restoration work in the Methow, according to BPA’s Wingert.  One of the many recent salmon projects underway in the Methow was the salmon acclimation facility in Carlton. One of the many recent salmon projects underway in the Methow was the salmon acclimation facility in Carlton. Next door to the federal hatchery is the Methow Salmon Hatchery, off Wolf Creek Road. It was built by the Douglas County Public Utility District in 1991 near the confluence of the Chewuch and Methow rivers at a cost of $10.2 million. It’s operated at that PUD’s expense, a cost of $1.9 million annually, by the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife. This hatchery has three permanent full-time employees and hires four to six part-timers each year. In addition to non-Methow related duties, it produces 170,000 Methow River spring Chinook smolts and 30,000 Twisp River spring Chinook smolts annually, according to hatchery specialist Leif Seaburg. Douglas County PUD also has built fish acclimation ponds on the Twisp, Chewuch and Methow rivers. All told, the Douglas County PUD has spent $35.6 million in the Methow since the early 1990s to mitigate the fish-killing effects of its Wells Dam, said spokeswoman Meaghan Vibbert. Included is $23.6 million for hatchery operations and maintenance since 1991. To mitigate the effects of its Rocky Reach and Rock Island dams, Chelan County PUD has spent $6.9 million in the valley: $5.7 million on hatchery operations since 2004 and $1.2 million on habitat restoration since 2006, according to public information officer Kimberlee Craig. The Chelan PUD acclimates summer Chinook south of Twisp at its own facility there and also raises spring Chinook under contract with Douglas County PUD at that utility’s Winthrop hatchery. The Grant County PUD has invested $15 million in the Methow on hatchery production since 2006, said spokesman Thomas Stredwick. The PUD produces summer Chinook—not federally listed as threatened or endangered—as part of its Federal Energy Regulatory Commission relicensing requirements for its Wanapum and Priest Rapids dams on the Columbia. The expenditure includes $5 million for the PUD’s new Carlton Summer Chinook Acclimation Facility, which the PUD is obliged to operate until 2052. Still, all this is not enough to do what the recovery plans mandate. A 2011 study for the Governor’s Salmon Recovery Office projected it would cost $5.5 billion just between 2010 and 2019 to implement federally required wild salmon restoration projects in Washington. But with the present funding, only one-fourth of proposed projects can be paid for, the report said. THE POLITICS BPA claims to have spent more than

$13 billion region-wide In 2008, all the salmon tribes affected by the BPA dams, except the Nez Perce, signed a 10-year peace treaty with the federal government called the Columbia Basin Accords. The tribes promised not to sue for fish-passage fixes at the Columbia River dams nor to litigate for outright removal of the Snake River dams. In exchange, they were promised $900 million in fisheries restoration money over the next decade. Funds flow from this accord to the Methow. Overall, the BPA claims to have spent more than $13 billion region-wide since 1978 to mitigate the dams’ effects on salmon. (This sum does not include the untold millions in federal taxpayer funds spent on salmon recovery in the Columbia Basin and throughout the Northwest, nor any Washington state tax funds.) The BPA’s $13 billion figure includes lost revenue from foregone power sales when water was spilled over dams to move juvenile fish to sea instead of being used to generate power. It also includes BPA’s cost of buying replacement power to fulfill its delivery contracts when salmon passage took precedence over power generation.  Spring Chinook salmon returns at Wells Dam. Image courtesy Upper Columbia Salmon Recovery Board Spring Chinook salmon returns at Wells Dam. Image courtesy Upper Columbia Salmon Recovery BoardHowever, “only” $2.84 billion of that $13 billion was used on the ground—or in the water—for salmon restoration, according to the Northwest Power and Conservation Council. It is the Portland-based agency authorized by Congress to tell BPA what it must do for fish. The governors of Washington, Oregon, Montana and Idaho each appoint two representatives to this council, which oversees the implementation of the Pacific Northwest Power Planning and Conservation Act, passed by Congress in 1980. The power council and the BPA are hinged at the hip in a sometimes tense relationship atop the salmon-funding pyramid. Deciding when river water should be used to produce electricity and when it should produce salmon lies at the heart of these tensions. The power council’s job is to balance an inherent conflict: Assuring that the Northwest has enough power and that its wild fish runs thrive. The council takes its cues from NOAA and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the federal agencies charged by Congress with implementing Endangered Species Act requirements for salmon. NOAA shut down leaky Methow Valley irrigation ditches in 1999 when the valley’s water and salmon war erupted and says it will shut down the Methow Valley Irrigation District (MVID) in 2015 if fixes are not made to its wasteful water delivery system.  NOAA could shut down the Methow Valley Irrigation District if it does not improve the efficiency of water delivery. more >> NOAA could shut down the Methow Valley Irrigation District if it does not improve the efficiency of water delivery. more >>This threat is driving the $9.6 million in ratepayer and tax expenditures to modernize the century-old MVID. However, only $750,000 of that sum is characterized as salmon restoration funding, according to Lisa Pelly, executive director of the Wenatchee-based Trout Unlimited-Washington Water Project, which was hired by the state Department of Ecology to manage the MVID project. It’s up to the power council to guide the BPA’s salmon recovery efforts. The council, not BPA, advertises for grant proposals from entities that want to compete for the coveted BPA salmon restoration funds. The council, not the BPA, approves both the applicants and their projects. But it’s the BPA that enters into contracts with the applicants. A contentious funding dispute arose in the 1990s when the Yakama Nation asked the power council to approve BPA ratepayer spending to restore coho, once the most abundant fish in the Methow. Those coho had been declared extinct. For one thing, a dam was erected across the Methow River 2.3 miles above Pateros in 1912 by the Nixon-Kimmel Co. of Spokane to provide electricity to Pateros, Brewster and Bridgeport, according to local historical researcher Barry George. The dam apparently was removed in 1929. "The coho wouldn't jump,

so they are gone." Coho are said to be poor jumpers. Some of the Chinook and steelhead managed to get over dams, said Seaburg of the Methow Salmon Hatchery. “The coho wouldn’t jump, so they are gone. The spring Chinook could jump over that dam,” he added. Whatever the case, the power council ruled that BPA restoration funds could not be spent on coho. They are to be spent only on fish that still exist genetically as “evolutionary significant units” in fish bio-speak, according to power council spokesman John Harrison, not on fish that have vanished. Yakama tribal officials, who did not respond to requests for interviews, apparently thought otherwise. They lobbied their case in the political arena and got their coho funding from the BPA, $245,000 of which now is spent annually raising coho at the Winthrop federal hatchery. Critics of hatcheries have argued for a long time that the fish they release compete for food and space with the struggling wild fish, threatening to overwhelm them and doom the hugely expensive effort to restore the sorry remnants of existing wild salmon populations. In 2012, 39 percent of hatcheries were violating recommended scientific methods for avoiding harm to wild fish, according to the Governor’s “State of Salmon in Watersheds” report. But Jorgensen, the Yakama’s fish biologist, sees an upside. If hatchery fish mate with wild fish, he noted, “they are considered wild fish.” THE ECONOMIC BY-CATCH A bewildering array of entities—federal and state government agencies, public utilities, Indian tribes and non-profit organizations—are busy funding, studying, restoring and protecting the upper Methow’s Valley’s rivers and creeks and stocking them with hatchery fish. Rebuilding and restocking the Methow’s riverine ecosystem has become a thriving enterprise. All this activity on behalf of salmon has the happy effect of helping boost the local economy, claims the “State of the Salmon in Watersheds” report. An estimated total of 500 “living wage,” short and long-term jobs have been created over the last 13 years in the Methow and the four other sub-basins of the Upper Columbia River because of salmon habitat restoration, according to Van Marter of the Upper Columbia Salmon Recovery Board. Though no one has kept track of the number of jobs created in the Methow by salmon restoration work, the local economic fallout “is not an insignificant amount,” he said. The availability of hundreds of millions of dollars for salmon projects has spawned a cottage industry of non-profit groups and consultants throughout the Northwest. They seek funding, manage projects, hire contractors, and perform studies for their clients. The non-profits, which cannot legally make a profit from their activities—after allowances for salaries and other expenses—have been key players in the valley’s salmon-related projects. Pelly’s Trout Unlimited organization, which has an office in Twisp and specializes in irrigation efficiency, is managing two major projects in the Methow, the roughly $2 million Chewuch Ditch piping project—which includes $318,547 in salmon-targeted funding—and the $9.6 million MVID upgrades. “We don’t make any money on these projects,” said Pelly.

The Winthrop-based Methow Conservancy, which focuses on land conservation, has been awarded $12.7 million from various sources for targeted salmon recovery projects over the last 13 years, according to executive director Jason Paulson. For-profit groups do not qualify

for salmon restoration funding The Okanogan-based Methow Salmon Recovery Foundation, a non-profit with an office in Twisp’s Riverbank building, has been awarded $14 million in grants since 2003, according to executive director Chris Johnson. His organization started out as a for-profit in 1998, but became non-profit in 2002. Operating as a for-profit “became too much of a burden on the people we were trying to help,” he said, because for-profit groups do not qualify for salmon funding. Johnson says his organization focuses on hiring local contractors to keep salmon restoration money that is spent in the valley churning in the local economy. THE END GAME In the unlikely event that dams were removed and salmon harvests stopped, more fish might return to the Methow River Basin. But could they survive in sustainable numbers in our rivers and creeks, given what more than a century of white settlement has done to them?  Biologists say salmon that do manage to return to the Methow won't survive without enough suitable habitat here. Biologists say salmon that do manage to return to the Methow won't survive without enough suitable habitat here.Biologists say no. They warn that protecting habitat is critical to ensuring the stability of naturally producing salmon in the Methow watershed—if there are adequate returns of adult spawners. It’s that caveat about returning adult spawners that makes this huge investment such a gamble. Whether enough fish get to, and return from, the sea to make these expenditures worthwhile depends not only on the ongoing habitat and hatchery work in the Methow sub-basin, which NOAA lists as one of the 16 most important in the Columbia Basin for fish recovery. It also depends on how willing fisheries managers are to set sustainable harvest levels and whether something more can be done about the nine dams that Methow fish twice must navigate in the polluted Columbia River’s main stem –not to mention the poorly understood, uncontrollable ocean and changing climate conditions. Robert A. Turner led NOAA’s negotiations with Methow irrigation districts when NOAA shut down the ditches for killing salmon back in the late 1990s. Now he’s NOAA Fisheries’ assistant regional administrator for sustainable fisheries.  In the late 1990s NOAA shut down Methow Valley irrigation ditches. In the late 1990s NOAA shut down Methow Valley irrigation ditches.“The actions we are taking are having a beneficial effect,” he told Methow Grist when asked to evaluate the efficacy of the salmon recovery effort overall. In the Methow, he added, that’s particularly true for improvements that have been made in fish passage and river and stream flow. “We need to turn our attention to hatchery reform there,” he added. Asked if more attention should be focused on harvest and hydropower improvements, Turner replied: “We try to ensure that harvest is consistent with recovery.” He reminded that by law, tribes are entitled to harvest even during ongoing salmon recovery efforts. As for the dams, said Turner, people in the Northwest have said: “‘We like to maintain hydropower but we want fish too.’” Politicians and bureaucrats who are trying to manage this conflict must “reconcile competing public values,” he added. "The net benefit isn't as rapid as

we would hope." Asked if he thinks the amounts spent on salmon recovery will succeed in saving them, Turner said there’s a “two-part” answer. Some successful interventions “are being masked by other things less in our control. The net benefit isn’t as rapid as we would hope.” Still, funds flow to the Methow because the odds are considered exceptionally good here for salmon recovery. As the author of one 2001 BPA salmon funding document put it: “The extremely competitive grants for these funds have always featured substantial biannual allocations for the Upper Methow because of its natural resource values –more than any other area of Washington.” (This was written to help justify the $3.75 million BPA expenditure in 2002 to purchase 600 acres from the Trust for Public Lands for a conservation easement adjoining the Arrowleaf property in Mazama.) If creating habitable homes for them were all that’s needed to save wild salmon, the habitat expenditures in the Methow doubtless would show quicker results. But as long as nothing much changes downstream, the efficacy of upstream expenditures remains hard to evaluate. That said, no downstream improvement would make it possible to have thriving populations of these remarkable creatures in the Methow without a suitable home awaiting them here. And then there’s this calculation: Amortized over the next 100 years, today’s cost of fixing mistakes made in ecological stewardship over the last 100 years may be seen as a wise investment by 2114. But only if the salmon survive.

1/27/2014 Comments

|