Methow descendant Elaine Timentwa Emerson displays a traditional Methow basket she made; the squares in the design represent Methow pit houses. - Photo by Solveig Torvik They called this place Met-whu - “low lying valley with blunt hills all around.” They were here for thousands of years. And then, quite abruptly, they were gone. But they didn’t quite disappear.

Their stories still cry out to their descendants from the land that we call the Methow Valley. The landscape where we farm and fish, bike and hike, is alive with memories we can’t see and voices we can’t hear.

For those of us who are non-Indians living on their ancestral lands, the story of the Methow people in the Methow long has lain tantalizingly just beyond our grasp. We have a few unsatisfying clues from archaeologists, educated conjecture and dry government documents, a few hints recorded by early settlers, and a brief glimpse of the historic meeting with the Methows by Canadian explorer David Thompson, who smoked with them at the mouth of the Methow River on July 6, 1811, and whose cargo was portaged across the Columbia’s Methow Rapids just below Pateros by “these friendly people.”

But the vague, hazy picture of pre-settler life here is starting to sharpen and fill in, thanks to the years-long efforts of local whites and Native Americans, scientists and scholars determined to uncover, or preserve and share, the history of the valley’s first people. One of the latter is Elaine Timentwa Emerson, age 70, a Methow descendant from Monse, north of Brewster.

Beadwork artist Tillie Timentwa Gorr is Elaine's sister. - Photo by Solveig Torvik “This valley was a breadbasket for native people,” she told the Jan. 30 opening session of the Methow Conservancy’s course, The Ecological History of the Methow Valley. Her ancestors gathered 15 kinds of berries and seven types of roots here, but not camas, she told the class. They hunted deer and Bighorn sheep and fished for salmon in the valley’s rivers and creeks. They lived in pit houses, and they fashioned pipes and bowls from rock gathered at Pipestone Canyon. Many came up here seasonally for the harvests; some stayed year-round.

“They taught us we had to work in tandem with the land,” Emerson said. “You take care of Mother Earth and go back and get whatever it is, it will be there for you,” she said, describing the harvesting ethic of the Methow. “Now I sound like an environmentalist. I’m not,” she assured her bemused listeners. Working in tandem with the land meant digging the cedar roots used to make baskets only when the sap was running so the tree could heal, she explained, not heedlessly taking things “by force” from the land. “We had to pray to Mother Earth for what we took from her.”

A fluent speaker of the Salish dialect spoken by the Methow, Emerson is the source for the spelling and translation of the word Met-whu. Some whites at first contact heard, and wrote, the name of the Methow people as “Smeeth-how.” According to Emerson, when an “s” is added to the beginning of the word, it refers to the people; when it’s dropped, the word refers to the land.

This descendant of a line of female basket makers and a male Methow canoe maker has been a leader in efforts at the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation to document, teach and preserve the language and culture of the Methow since she graduated from Wenatchee Valley College in 1964 and returned home to the family’s cattle ranch to realize that tribal arts, traditions and language were disappearing.

Disease killed many of the elders who knew traditional crafts, said Emerson. “They left no apprentices.” A basket-weaver, Emerson and her beadwork-artist sister Tillie Timentwa Gorr, 67, credit their independent-minded Methow mother Julian Michel Timentwa - who never attended the mission schools - for impressing on them the need to learn and retain their people’s ancient ways.

Born in 1905, Julian first came up to the Methow as an infant strapped to a cradleboard behind her aunt on horseback over the Chilowist Trail, which comes up over Three Devils Mountains from Chilowist Creek and down the Benson Creek drainage. Several times each year Julian brought her daughters to the Methow, where they learned how, when and where to dig roots, harvest berries and utilize other abundant native resources in the valley. “You don’t know how fortunate you are up here,” Emerson told the class.

Julian taught her daughters to dig for cedar roots at the base of Goat Wall in Mazama, where the cedar is of exceptional quality for basket-making. “It doesn’t split. It doesn’t fray,” Emerson explained in an interview. “We would pray where we did the cutting. She would sing. Then she would cry to herself. I would tell her not to cry, it doesn’t do any good. She said: ‘I can still hear them singing. They’re not here any more.’”

Julian Michel Timentwa at age 18. Photo courtesy Elaine Timentwa Emerson and Carolyn Schmekel “They had songs for everything,” said Emerson. “And we don’t know any of them.”

The stories of what happened here still haunt them. “When we go there, we still feel our people there,” Gorr told Grist. She and Emerson told of a young Methow woman who was raped by a white soldier and secretly gave birth to a child she immediately killed and buried in a shallow grave in a location they will not make public. A group of Methow hunters later happened upon the grave and re-buried the child properly. After that, whenever an infant died, it was brought to that place and buried with the first child “so it wouldn’t be alone,” said Emerson.

Their fears regarding desecration of the graves of their ancestors stem from sorry experience. It was common in the old days to leave stone bowls upside down on graves, said Emerson, but the bowls vanished from the graves when whites arrived. And in 1940, according to Emerson, 40 Methow bodies were dug up and removed by white people from a native cemetery between McFarland Creek and Gold Creek, and no one knows who took them or where they went. “They never gave them back.”

Julian and Alex Timentwa. Photo courtesy Elaine Timentwa Emerson and Carolyn Schmekel Julian began to teach her beadwork when she was six, Gorr said. But she wouldn’t let Gorr make anything completely on her own until she was 13. When Gorr finished the first bag she had beaded alone, her mother carefully examined it and praised her for the smoothness of her beadwork. “But it’s all wrong,” she told her daughter. Julian cut away the beads and told Gorr she had to start over.

“I stood there crying and I asked her: ‘Why didn’t you correct me?’ `I wanted you to see it both ways,”’ Julian answered. While Emerson mastered basket-making, Gorr mastered the art of beadwork and eventually she would spend more than five years, working every day to bead a traditional dance costume for her son.

The area where Wolf Creek joins the Methow River was sacred to the Methow, said Emerson, and young men would set out on vision quest journeys from there to Mt. Gardner. The Wolf Creek area under Highway 20 was carbon-dated in the 1980s by the Washington State Department of Transportation as having been used by Indians 3,000 years ago, according to North Cascades National Park archaeologist Bob Mierendorf, who told a subsequent Conservancy class that obsidian from Three Sisters in Oregon was found there.

Mierendorf’s own excavations of an ancient fire pit at Cascade Pass that contains “textbook” layering of dating material spewed out by volcanic eruptions recently revealed that native peoples were using the pass as long as 9,000 years ago, he told the class. Eastside tribes are thought to have carried such items as dry-air cured salmon and dogbane--called ‘Indian hemp’ and valued for fishing nets--over the pass to the west side.

Julian Timentwa in 1966. She died in 1985. Photo courtesy Elaine Timentwa Emerson and Carolyn Schmekel Methow descendant Hazel Burke, 84, corroborated that cross-Cascade trade was common. She told Grist about a male and a female Methow who set out to cross the mountains carrying hemp for trade from an upper-valley summer camp where her family was gathering food. The two returned to the camp, with the west side trading completed, within the two-week period that her family was staying in the upper valley.

Indian carrots grew in great abundance on the land where Sun Mountain Lodge now sits. But like other native foods all over the valley, the carrots vanished wherever the land was sprayed, Emerson said. They gathered bitterroot and Indian potatoes – the latter roots of what we call Spring Beauties - at Twin Lakes, and hunted in the Goat Peak area.

“The Methow wasn’t fenced when I was a little kid,” said Burke, who came here frequently gathering native foods. “There are new buildings all over where we used to dig bitterroots,” she said, and her people over time increasingly have been shut out of their ancestors’ ancient gathering grounds.

Julian urged Emerson to “write everything down,” to record on file cards the stories and details of their culture. She’s passing this storehouse of information on to young Methow descendants, “to try to show them that they came from a place,” as she told the class. “The culture is on the brink of dying out,” she said. “When our people are gone, the art isn’t going to die,” she declared.

The traditional territory of the Methow people encompassed most of the Methow River drainage except the northernmost portions of the Methow and Chewuch river drainages, according to E. Richard Hart, a Winthrop historian who is under contract with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation as an expert witness in treaty cases. The Methow’s territory was bounded on the south by the crest of the Sawtooth Ridge and on the west by the crest of the Cascades. On the southeast corner it included several square miles east of the Columbia River and includes today’s towns of Azwell, Pateros and Brewster as well as the land around the Methow Rapids, Monse and Malott, Hart said.

Beadworker and Methow descendant Hazel Burke, 84, remembers her grandfather's account of being driven from the Methow. - Photo by Solveig Torvik At least 10 Methow village sites have been identified, according to Hart. One, called “Bluff at the Mouth of the River,” was near Pateros. A cluster of villages was near Malott and Chilowist. Another was upstream from where Benson Creek flows into the Methow. Others were in Twisp - which means “yellow jacket,” according to Emerson - near the confluence of the Twisp and Methow rivers, and another where the Chewuch River flows into Winthrop. Settlements also were located where Eight Mile Creek flows into the Chewuch, and summer settlements existed in Mazama and at Goat Wall. Small camps for fishing, hunting and berrying also were located on War Creek.

Exactly how and when the Methow were removed from the valley is shrouded in mystery. White settlers recorded the anguished lamentations of the Lemhi Shoshoni - Sacajawea’s people - as they were forcibly marched by soldiers across the southeastern Idaho desert from their lush Lemhi valley home to live on the barren Fort Hall Shoshone-Bannock Reservation. But no non-Indian accounts have come to light that describe a similar Methow expulsion.

Yet Burke said her grandfather, Harry Kulpschickin, who died sometime in the 1940s at more than 100 years of age, told her they were “driven out by soldiers, herded like animals. They were really hurt over that,” said Burke, who was raised in Malott. “My grandfather used to get kind of angry when he’d tell me about when we moved away from there.” Gorr added that she has been told that “some of them were still cooking on their fires when they (the soldiers) came.”

“I have never been able to find any record of troops removing the Methow Indians from the valley,” said Hart, who was instrumental in persuading Emerson and Gorr to share their knowledge with the Conservancy class. “But the tradition is very strong among the Methow today.”

“In 1886 when the Columbia Reservation opened, the (government) agent was located in Colville, 40 miles from the east boundary of the reservation,” said Hart. “I kind of doubt he would have gone all the way over to the Methow Valley to evict Indians. Once the reservation was opened, it came under the jurisdiction of the General Land Office. Non-Indians could have appealed to the land office to have Indians removed. We just don’t know how it happened.”

Tillie Gorr and some of the beadwork she will display at the June 9 opening of the Methow Valley Interpretive Center at TwispWorks. - Photo by Solveig Torvik

The Methow Valley was part of a large swath of real estate far from Chief Moses’ original Moses Lake territory given to him by the federal government and designated the Moses Columbia Reservation. But insistent clamoring by whites wanting to farm and mine here led to opening the Methow Valley to white settlement in 1886.

“Chief Moses, he didn’t live here. He had no ties here. He ceded the land,” said Emerson, whose anger over this historic injustice is still palpable.

The Methow were given the choice of moving to the Colville reservation, now occupied by 12 tribes, or staying on what had been the Moses Columbia Reservation. If they stayed, each head of family or male adult legally was entitled to an allotment of one square mile. However, government agents did not provide allotments to every male adult, or even each head of household, according to Hart. Instead, they grouped those allotments so that the tribal village sites were held in trust by the United States for the Colville Confederated Tribes.

Part of a beadwork bag Tillie Gorr made for her son after he successfully hunted his first elk. - Photo by Solveig Torvik. When the land allotments were parceled out, the Methows were confined to three settlements along or near the Columbia River, according to Hart. These were at Antiwine Creek near Wells Dam, the Peter In-perk-shin Settlement between Wells Dam and the mouth of the Methow, and Captain Joe’s Settlement near Pateros, where the last Methow family in the valley still lives on the only remaining Methow allotment.

By 1900, most of the Methow had moved, or been moved, to the Colville reservation, Hart said. Almost all of the Methow’s allotments somehow passed into non-Indian hands. The process under which these land transfers occurred was often corrupt, Hart said, and he has found cases of outright theft.

The Methow also were able to choose land under the Homestead Act and some did so. But Emerson told the class that some of these historic foragers did not understand the legal requirement to farm and “prove up” the land within five years and so lost their homesteads.

Historical records indicate that the Methow population was severely depleted by smallpox epidemics that began in the late 18th Century, according to Hart. Their numbers are thought to have been cut in half during the first half of the 19th Century, then depleted by half again by 1900. In 1883 there were just over 300 Methow, which suggests that the population before white contact may have been as high as 1,200, according to Hart’s research. Today about 100 descendants live in the Malott, Chilowist and Pateros area, according to Emerson, who said she does not know the exact total number of Methow descendants still living. “The real Methows are all gone though now,” she added.

“Our mother said the saddest memory she had was of the train whistle,” said Gorr. Julian, who was married to Alex (Jack) Timentwa, told her family that a delegation of tribal leaders had gone to Washington, D.C., for a big meeting. “When they got home, they were sick,” Julian related, and many people died of the disease the men carried home. Gorr said she does not know what the disease was nor when it happened. Afterwards, every time the train passed, “all of the women and widows would stand in a line when the train went by,” wailing in sorrow, Gorr said. They covered their heads and turned their backs on the train to protest what had happened.

Against the backdrop of this compelling history, Emerson and Gorr have agreed to lend their own tribal handiwork, as well as old family photographs, for a display celebrating the June 9 opening of the Methow Valley Interpretive Center at TwispWorks, according to Carolyn Schmekel, who, with her husband Glenn, is among several people who’ve been working for years to build bridges of trust between the descendants of the valley’s original and present inhabitants.

Methow descendants say they’ve encountered hostility from white landowners during past attempts to forage for native foods on what is now private property. Julian, when some white men tried to evict her from gathering near Goat Wall, shouted, “I’ve been here longer than you!” Gorr recalled. Schmekel said a goal of the center is to compile a list of valley property owners willing to let Methow descendants harvest native foods from their lands.

Despite loss of access to their ancestral breadbasket, they periodically return anyway, Emerson told the class, to check on the graves of their people and keep an eye on how things are going here.

“It’s always a good feeling to come back. It’s like having a sense of belonging.” |

Methow descendant Elaine Timentwa Emerson displays a traditional Methow basket she made; the squares in the design represent Methow pit houses. - Photo by Solveig Torvik

Methow descendant Elaine Timentwa Emerson displays a traditional Methow basket she made; the squares in the design represent Methow pit houses. - Photo by Solveig Torvik Beadwork artist Tillie Timentwa Gorr is Elaine's sister. - Photo by Solveig Torvik

Beadwork artist Tillie Timentwa Gorr is Elaine's sister. - Photo by Solveig Torvik Julian Michel Timentwa at age 18. Photo courtesy Elaine Timentwa Emerson and Carolyn Schmekel

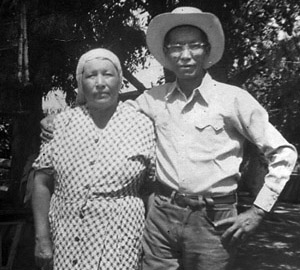

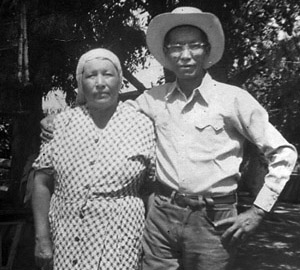

Julian Michel Timentwa at age 18. Photo courtesy Elaine Timentwa Emerson and Carolyn Schmekel Julian and Alex Timentwa. Photo courtesy Elaine Timentwa Emerson and Carolyn Schmekel

Julian and Alex Timentwa. Photo courtesy Elaine Timentwa Emerson and Carolyn Schmekel Julian Timentwa in 1966. She died in 1985. Photo courtesy Elaine Timentwa Emerson and Carolyn Schmekel

Julian Timentwa in 1966. She died in 1985. Photo courtesy Elaine Timentwa Emerson and Carolyn Schmekel Beadworker and Methow descendant Hazel Burke, 84, remembers her grandfather's account of being driven from the Methow. - Photo by Solveig Torvik

Beadworker and Methow descendant Hazel Burke, 84, remembers her grandfather's account of being driven from the Methow. - Photo by Solveig Torvik Tillie Gorr and some of the beadwork she will display at the June 9 opening of the Methow Valley Interpretive Center at TwispWorks. - Photo by Solveig Torvik

Tillie Gorr and some of the beadwork she will display at the June 9 opening of the Methow Valley Interpretive Center at TwispWorks. - Photo by Solveig Torvik Part of a beadwork bag Tillie Gorr made for her son after he successfully hunted his first elk. - Photo by Solveig Torvik.

Part of a beadwork bag Tillie Gorr made for her son after he successfully hunted his first elk. - Photo by Solveig Torvik.