home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

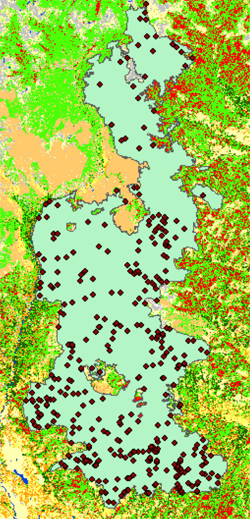

Silver Lining  Parts of the Tripod Fire burned in a patchy mosaic. Parts of the Tripod Fire burned in a patchy mosaic.Lightning started the Tripod Fire July 4, 2006. It burned through 175,000 acres and $80,000,000 before being declared out October 31. It was the largest fire in recent Washington State history. Invited by the Methow Conservancy, a packed crowd at the Twisp River Pub listened to Forest Service employees tell how they have turned the huge fire into a research tool. When District Ranger Mike Liu asked how many in the room had been in the Methow Valley during the Tripod Fire, most raised their hand. Immediately following the Tripod Fire, crews worked to restore fire lines, control erosion and noxious weeds, repair fences and roads, salvage one million board feet of lumber, and repair trails and recreation areas. Then the research started. From 1940 (a year after the North Cascades Smokejumper Base opened) until 2006, the Forest Service suppressed 303 fires in the Tripod Fire area, according to Richy Harrod from the Okanogan-Wenatchee Forest staff. What helped slow or stop the spread of the Tripod Fire, however, was previous forest fires - it burned around or bumped up against the Forks Fire (1970), Thunder Mountain Fire (1994) Thirtymile Fire (2001) Farewell Fire (2003), Remmel Lake Fire (1929) Horsehoe Fire (1929) Toats Coulee Fire (1930) Isabel Fire (2003) and Boulder Creek Fire (1926).  The brown squares are fires that were previously suppressed inside what became the Tripod fire. The brown squares are fires that were previously suppressed inside what became the Tripod fire.Forest managers would like to move forest back into a more ‘natural’ mosaic of young, medium and old forests. Tripod Fire research is helping with that. “We’re beginning to think closely about landscape scale,” Harrod said, as he showed the crowd a series of data-heavy maps covering large areas and showing vegetation, fire severity potential, and the potential for disease and insect invasions. About 60% of the Tripod Fire area was burned with moderate to high intensity. Thinned forest inside the area did not fare nearly as well as forest that had been thinned and then burned with prescribed fire. “Thinning alone is not a replacement for prescribed fire,” said Ranger Mike Liu. The Tripod fire burned 128,000 acres of lynx habitat. By radio-collaring 13 lynx in the area researchers learned that they tended to remain near, but not in, the burned area. One lynx left, making his way to Kamloops, B.C. Forest Service biologist John Rohr said it would take 10 to 15 years for lynx to return to the more severely burned areas. However, moose appear to be moving back in, attracted by vegetation in the moist areas. In one place where an aspen grove burned, water started flowing again for the first time in years and aspen are re-sprouting. Rohr said the fire did not cause habitat improvement or loss, but more of a habitat change to a more diverse landscape. Fisheries manager Gene Shull explained that, in the short term, fires increase stream temperatures and sedimentation. But over a longer time, an increase in large woody debris, gravel and streamside vegetation will likely create better fish habitat than before the fire. In the upper Chewuch, large wood debris in streams has doubled and logs are expected to gradually move down river improving habitat at lower elevations. Water temperatures are also starting to drop after an initial rise. The seemingly catastrophic Tripod Fire may serve up a silver lining of healthy forest diversity and research that will help refine the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest’s forest restoration strategy, a work in progress. 2/9/2012 Comments

|