home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

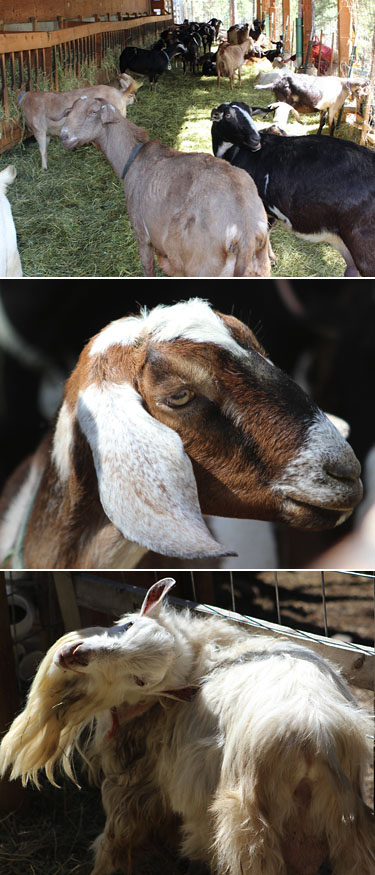

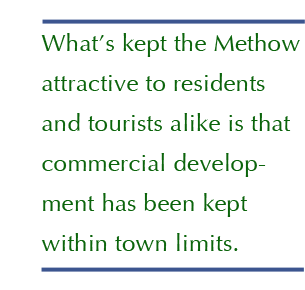

Life's Work  Vicky and Ed Welch. Vicky and Ed Welch.On September 2, 1972, Ed and Vicky Welch were driving from Oregon to Tonasket to scout out property for a possible move to Washington. Approaching Pateros, they heard a local radio announcer say that the North Cascades Highway was opening that day for the first time. On an impulse, they decided this was an occasion worthy of a detour up the valley, and they got their first look at the Methow on that historic day. “Wow! This really is a beautiful place,” Vicky remembers thinking. So they found a real estate agent, Doug Wallace, who showed them some properties, none of which they liked. After a couple of days of fruitless searching, he told them: “Okay, I’ll sell you my place,” Vicky recounts. Which is how they came to own the 87 forested acres on a hillside up the Twisp River that became Sunny Pine Farm. First it was a post and pole operation, then they tried logging. After that, they grew vegetables commercially for 10 years. “It was a lot of heavy lifting,” says Vicky. “We thought cheese would be lighter,” she smiles. Today, Sunny Pine is a dairy with 56 milk goats. It produces organic cheese and yoghurt for customers as far away as Spokane, the Wenatchee Valley and Portland as well as in Seattle, where it can be found in five Whole Foods stores. Next is distribution to a Skagit Valley co-op and Bellingham, Chelan, Okanogan, and Leavenworth, says Ed. The Gabby Cabby delivers the dairy’s wares to out-of-valley customers, as well as the farm’s lavender products. For the better part of a decade, the Welches invited people who wanted to be part of a farm to live with them and work it. But many of those who showed up were “urban refugees” ill suited to the rigors of farming, and some had addiction problems. “We ended up asking them all to leave,” Ed says. Even so, the Welches, both 66, have continued for many years to offer agricultural internships on the farm, now managed by Lonnie and Jamie Trask.  Sunny Pine Farm is now a dairy that produces goat milk cheese and yoghurt. Top: The dairy goats are milked twice a day. These nannies had all delivered their kids. Middle: Nubian goats provide dairy products at Sunny Pine Farm. Bottom: A Sunny Pine billy goat. Sunny Pine Farm is now a dairy that produces goat milk cheese and yoghurt. Top: The dairy goats are milked twice a day. These nannies had all delivered their kids. Middle: Nubian goats provide dairy products at Sunny Pine Farm. Bottom: A Sunny Pine billy goat.“They have nurtured a whole generation of young people who had come here looking to live on the land. They taught them and fed them and became their friends. Dozens of young farmers got their start with Ed and Vicky,” says Maggie Coon, who lived at the farm when she first arrived in the valley in 1975. “Vicky taught me the difference between a vegetable and a weed.” The couple has a “sixth sense” about caring for goats, which they’ve trained to be pack animals for trips they love to take into the backcountry, according to Coon. But their first acquaintance with goats was inauspicious. As a joke, family members gave them one as a housewarming gift when they were moving their furniture out of storage in San Francisco to Oregon, where Ed, who has a degree in forestry, was to take a job with the U.S. Forest Service. Unburdened by any knowledge of goats, they put the animal into the moving van with the furniture, neglecting to tie it up. The goat, being a goat, had its goatish way with their furniture, says Vicky. In 1976 she and Coon co-founded the Methow Valley Citizen’s Council, which spearheaded the contentious, 25-year fight against the Early Winters ski resort in Mazama. A dogged defender of the Methow’s open spaces and natural environment, Vicky became well versed in the mind-numbing nuances of zoning, state water law and shoreline regulations. And she served as a sharp-eyed watchdog on the county commissioners’ often reluctant land use planning efforts. “She was really the glue that held the effort together to help people understand how important it was that we have a comprehensive plan” governing land use, says Coon. “Vicky probably has driven back and forth to the county courthouse as much as anyone living here today. She never complained. And she never sought the limelight.” Vicky dismisses her own efforts, which recently have been hampered by her battle with cancer, as being “of very little effect.” And, she adds firmly, “The new comprehensive plan is far worse than the old one.” It focuses too much on property rights issues to the detriment of intelligent land use planning, in her view. What’s kept the Methow attractive to residents and tourists alike is that commercial development has been kept within town limits, leaving the open spaces between towns, she argues. “That’s what’s kept the valley looking nice.” But the pressure is on to change that, she warns, and if it happens, she fears the Methow’s landscape will be blighted up and down the valley. Between 1983 and 1987, the Welches spent six to eight months a year in Argentina as managers, gardeners and landscapers on a 130,000-acre cattle ranch that could be reached only by horseback. Then, in 1987, their son Arthur was born. He had Down syndrome and died at age 10. “The two of them poured their heart and souls into working with him and helping him have a good quality of life,” says Coon. After Arthur’s death, they adopted then 10-year-old Gary, who lives in California. In 1998 the couple returned from a retreat on the west side of the state to discover their home had burned to the ground due to an electrical malfunction. They lost everything. At the retreat, they had been camping in their tent. “So we just put up our tent,” says Vicky. Methow style, neighbors pitched in and offered them housing. “They took good care of us,” she says of her neighbors.

“I thought I’d probably end up as a professor of Indian studies,” Vicky explains, and she expected to travel to India on a bequest left to her by her grandmother. Instead, friends persuaded her to see South America first, so she rounded up traveling companions bound for Santiago. They set off in October. By New Years’ they’d reached Ecuador. At the time, much of the Pan American Highway was a one-lane, unpaved dirt track. In Santiago, she left her car for safekeeping and advertised at the Peace Corps office for people to accompany her south to Patagonia. Ed, serving in the Peace Corps, fortuitously arrived in Santiago on a two-week vacation just in time to join the trip, which included a third traveler. The threesome climbed Patagonia’s snowy volcanoes. Afterwards Vicky and Ed continued their explorations together. Patagonia was cold, snowy and rainy and they found themselves unprepared. So they just knocked on people’s doors at the end of each day to ask for shelter. “We said we were on our honeymoon, which it turns out we were. It just came before the marriage,” Vicky chuckles. Once, caught in a blizzard in a national park in Patagonia, they dined on a wild rabbit caught by a park ranger’s dog and cooked over a huge bonfire lit to ward off the unrelenting snow and rain. But this was just the beginning of their culinary exploits. Lodged free of charge in a “pleasant” jail that, unlike the hotel they had abandoned, didn’t leak rainwater on their beds, they met European jail lodgers who advised them to head for the Amazon. They returned to Santiago to find Vicky’s car impounded by the military regime that seized control after President Salvador Allende’s assassination. They never saw it again. Ed was now six weeks overdue at work from his vacation, but he had only one month left to serve. Peace Corps officials released him early, and they set out to explore Bolivia and Brazil with another couple.

Armed with a single-shot .22 rifle and a machete, they embarked in a wooden dugout canoe down the Mamore River, an Amazon River tributary. Before departing on their Amazonian jungle adventure, they prudently paid a local hunter to give them a few pointers on staying alive. “We recognized we didn’t really know how to survive in the jungle very well,” says Vicky in a bit of understatement. “It was wild jungle. I thought it was very exciting.” They had brought the alcohol on the advice of people who said it could be used to trade with the Indians. But the Indians they met didn’t want alcohol, they wanted medicine. Once, Vicky recalls, “They brought in a sick baby covered with sores,” but the Americans had no medicine to offer. “Not to be able to help was hard.” The dried meat they brought turned out to be full of maggots, but Vicky gamely improvised. Brushing the maggots off the meat into the river one day, she noticed that little minnow-like fish swam up to eat them. So she caught the fish. “I made minnow pizza for dinner. We just had to pretend they were anchovies,” she says. Driven by hunger, they dined on lizard tail, snake and exotic birds. One pre-historic-looking bird specimen sported “horns” on its wings and head; it turned out to be full of lice when the women plucked its feathers. They ate turtle egg omelets and mastered the difficult skill of extracting meat from turtle shells. When they returned to civilization, says Ed, “We became vegetarians” for awhile. The foursome’s most harrowing adventure occurred when they were camped at a shed erected on a lake by the Bolivian navy, an organizational artifice of that landlocked nation’s unbounded optimism. Just before the travelers arrived, a jaguar killed one the of navy’s sailors near the camp. At the lake camp, a couple of miles from the river, the Americans were allowed to use a small boat belonging to a local family. One day the sailors asked to use it, promising to bring it back. Instead, they left it on the other side of the lake, some two miles away, according to Ed. So, rifle and the machete in hand, the two men set off to retrieve the boat in late afternoon, leaving the two unarmed women behind. But the men lost their bearings in the thick jungle, and before they could figure out where they were, equatorial night enveloped them. Then they heard a jaguar scream. “It was right near us,” says Ed. The men clambered up into a tree and took turns keeping watch during the night. Back at camp, the worried women called out into the darkness, hoping to guide them back, but there was no response. Anxious and defenseless, the women spent a memorable night in the jungle. “It was terrible not to know what had happened to them,” Vicky says, but at daylight the men sorted themselves out and returned to camp with the boat. Continuing down river, the group eventually reached Manaus, Brazil. And when they were done exploring Brazil, there was still more to see and do. “We didn’t want to miss the Caribbean,” says Vicky, smiling at the memory. “We hadn’t spent our last cent yet.” 4/17/2013 Comments

|

Ed and Vicky met in Santiago, Chile, in 1970. She had driven to Chile in her own car from her home in the Chicago area. The day before she left, she had taken her oral exam for her master’s degree in Indian studies from the University of Wisconsin.

Ed and Vicky met in Santiago, Chile, in 1970. She had driven to Chile in her own car from her home in the Chicago area. The day before she left, she had taken her oral exam for her master’s degree in Indian studies from the University of Wisconsin. During their three months in Bolivia, the country had three revolutions. Twice they were written up in the local papers as being guerrillas. Their passports were confiscated, and they traveled 10 hours by truck to persuade an army general to give them back.

During their three months in Bolivia, the country had three revolutions. Twice they were written up in the local papers as being guerrillas. Their passports were confiscated, and they traveled 10 hours by truck to persuade an army general to give them back.