| |

Back to Africa! Off to Mauritania and the Sahara Desert in August!

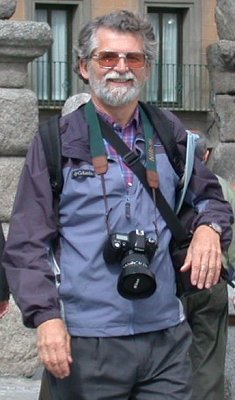

An excerpt from Bill Hottell's unpublished

memoir

In 1982-1983 Diana and I decided to take off a year and travel across Africa. We had backed off world travels for several years when we moved to Twisp and settled into the Lightning Double ‘R’ Ranch on the Twisp River. But then we both read Isak Dinesen’s 'Out of Africa' and Antoine de Saint Exupery’s 'Wind, Sand and Stars', and suddenly we felt the call to adventure once again. Back to Africa! Off to Mauritania and the Sahara Desert in August! In 1982-1983 Diana and I decided to take off a year and travel across Africa. We had backed off world travels for several years when we moved to Twisp and settled into the Lightning Double ‘R’ Ranch on the Twisp River. But then we both read Isak Dinesen’s 'Out of Africa' and Antoine de Saint Exupery’s 'Wind, Sand and Stars', and suddenly we felt the call to adventure once again. Back to Africa! Off to Mauritania and the Sahara Desert in August!

The trip began with disaster. After we landed in Nouadhibou (formerly St. Etienne when this was part of French West Africa) at the western edge of the Sahara Desert, Diana and I were standing in the airport terminal waiting for baggage to arrive. But our two backpacks were not on the baggage cart when it rolled in from the plane. So I knew that all our clothes and other possessions for an entire year were still on board the Air Mauritania plane which was far across the runway and ready for take-off to the next stop, Nouakchott. At that moment my adrenalin started pumping and I burst into action. I leapt over the airline counter, ran out the back door of the terminal and sprinted across the entire runway to the airplane. The engine was running and the propellers were spinning but the pilot’s outside door was still open, so I shouted up to the captain, then spotted luggage piled behind him in the cockpit. I instantly leapt high and climbed into the cockpit, scrambled around the captain and started searching feverishly through the luggage. Our backpacks were NOT here. “Where is the rest of the baggage stored?,” I asked the captain in French. “There is some back in the tail section.” So I leapt out of the cockpit onto the runway, raced around the plane to the passengers’ door which was now closed tight for take-off. I actually grabbed the large circular “handle” and slowly turned it counter-clockwise to try to open the door. But from the inside someone slowly turned the handle back and closed it tight again. Once again I turned the handle back in the opposite direction and this time I was able to muscle the door open. I burst in past the flight attendant, scanned the area intensely and spied the remaining luggage crammed back into the tail section. I had to rummage through many suitcases and cardboard boxes, but finally my heart leapt with joy when I finally found our gear. As the plane flew off I looked both ways and toted the backpacks across the runway.

This was our first hour in Africa! The perfect way to begin a year-long journey. And this is why I enjoy traveling in the Dark Continent: you have to be alert all the time. That is when I feel truly alive.

From the “Baggage Claim” section of the terminal we advanced to the “Immigration” counter. Here the suspicious official confiscated our two passports and sent them off four hundred miles away to Nouakchott where they were lost. The officer said, “Come back tomorrow…. And go to the office of police commandant.” The next day we went to police headquarters, but the commandant was very unhelpful and unfriendly. He merely said, “Come back tomorrow,” so it was several days before we even learned that our passports were not here in Nouadhibou at all. But every day we went dutifully to the commandant’s office and every day he said, “Come back tomorrow.” Sitting in the waiting room we had a chance to watch a criminal suspect awkwardly shuffle across the room. Both of his wrists were chained to his ankles with huge padlocks, so he had to bend over and scuttle along like a human crab dragging the heavy chain whenever a gendarme ordered him around.

When I learned that our missing passports had been sent off to the capital I tried to call the U.S. embassy but this was impossible because none of the telephones worked. Yes, none of the telephones in town worked.

Then the first miracle happened. We met two Frenchmen who just happened to be here on assignment from France for two days to work on the country’s phone system. They agreed to help me call the embassy in Nouakchott. They took me to the city’s telephone headquarters. The building was a large, empty room with a slab concrete floor. Spread over the entire surface of the floor were thousands of colored wires all tangled up. Some wires were leading nowhere, others were plugged into broken telephone equipment that didn’t work. One of the Frenchmen, Monsieur Riard, handed me a dead phone and said to try a call as soon as he connected some wires. Then he climbed up onto the roof of “telephone central” and struggled to hold some wires together while his colleague shouted, “Quick! Dial the phone number!” The call actually went through to the American embassy for a moment but suddenly went dead. We attempted another call but the line was so crackling with static that I could barely hear the voice at the other end. Then the line went lead again. I was eternally grateful for M. Riard on the roof who utilized all his technical skill and physical strength to stretch and connect wires until I heard another, “Quick! Dial the phone number! “This time I was able to speak to the American consul, but I had to scream into the phone. His crackling voice said that he would try to locate the missing passports. Then the phone went dead again.

After the miraculous phone call to the embassy, I needed a third miracle. Thanks to the U.S. consul the two passports were found lying on a table at the airport in Nouakchott! Then, because the president of the country was to fly here in a few days, the consul arranged for the president’s personal pilot , “a Frenchman with a bushy mustache,” to carry our passports and hand deliver them to me. Once again I found myself sprinting across the airport runway as the president’s plane taxied to a stop. I received the precious envelope from the pilot, ripped it open and kissed the two American passports. The eight days of tribulation were at an end and now we could finally get the fuck out of town.

Later, at the embassy in Nouakchott, when we met the U.S. consul, Ed Carrolll III, to thank him, he said that we were only the second Americans to visit this country during the eight months of his tenure. No Americans visit Mauritania!

Meanwhile back on the first day of our arrival in Africa when our luggage very nearly vanished and our passports were confiscated, Diana and I walked out of the airport terminal, jumped into the back of an army truck with a dozen soldiers and rolled into downtown Nouadhibou. Without a passport there were two problems. At any road check in the country we would be arrested and thrown into jail. I pictured ourselves scuttling around with wrists chained to our ankles. And secondly, we could not change money into local currency, ouguia. We could not buy any food. We could not pay for any lodging. So we just stood in the middle of the deep-sand street and wondered what to do next. The final miracle was a tall, distinguished black gentleman dressed in a maroon, neck-to-ankle caftan. He walked up to us and soon offered his home where we could sleep on the floor and eat meals until the lost passports reappeared.

This gentleman was Soumaree Hamidou. He spoke four languages and had worked at the radio station in the capital until he was re-assigned (banished) to this god-forsaken town in god-forsaken Mauritania. Soumaree’s house had a small open-air courtyard with one lone plant in the sand, a foot-tall hibiscus with only one red flower. A snapshot moment: each morning after washing his face, Soumaree carried the cup of used wash-water to the courtyard, knelt down reverently beside the little plant and watered it. That red hibiscus was a splash of color in the otherwise yellow-brown world of the Sahara.

Now that we were able to leave Nouadhibou we caught an iron ore train hundreds of miles into the Sahara. There is only one train in the country, a French-built freight train that runs 400 miles straight into the Sahara to a mountain of iron, then hauls the ore back to Nouadhibou on the Atlantic coast. There were, of course, no passenger cars, but rather than ride in an empty ore car we were lucky enough to sneak into the caboose as stowaways. The train passed encampments of Polisario tribesmen who were at war with Morocco, and the next day we disembarked at the little desert village of Choum in the middle of nowhere. Here we climbed into the back of a Toyota pick-up truck, a “group taxi,” for the endless and sweltering drive from Choum to Atar. The other passengers were young Arabs who passed the time by having us teach them to say dirty words in English. The pickup drove for hours across the desert where there was no road, only occasional tracks in the sand. When I started seeing parched bones of camels lying on the sand I knew that we were really off the tourist route.

Eventually the group taxi arrived in Atar. The 'Lonely Planet Guidebook' had described Atar as an oasis in the Sahara. Well, it did have some date palms, but it was also the hottest place I have ever imagined. This was near the hottest spot ever recorded in the world. As an “oasis” Atar was a bitter disappointment, but we did find a “restaurant.” Unfortunately, the holy month of Ramadan was still in effect, so no food could be eaten until after sunset. “No food nor drink shall pass your lips between the rising of the sun and setting of the sun.” Incidentally, this injunction from the Koran ensures that many devout Muslims are so vigilant to avoid consuming any moisture that they hawk up phlegm and spit often during the daylight hours. I have also observed that after two or three weeks of fasting, some Muslims can get irritable and cranky. Meanwhile we hung around the mud hovel that passed as a restaurant until the sun finally set and the establishment could now serve food. There was only one item on the menu (actually, there was no menu), so we ordered one bowl of camel stew. Now, camels are so valuable that they are not slaughtered until they reach a very advanced age and are worthless as a pack animal. As a result, camel meat is old and very tough to chew.

As I sat chewing the leathery camel meat and watching the sunset fade into twilight over the vast Sahara, I had an epiphany: this time the inspiring figure of Tom Sawyer had really led me off the beaten path, had led me to adventures far, far away from home.

Before we left Mauritania, we stayed in Nouakchott, which is one of the strangest capital cities in the world. Nouakchott has only two paved streets. It has no street lights. It has no busses. Nouakchott has no street names and there has never been a map of the city. It has no television channel. There are 2,000 power poles but no power plant to supply them. The city gets a little electricity, about two hours a day. There is no grass for the goats and camels; they have nothing to eat but garbage and trash in the streets. There is a large sports stadium, built as a gift by the Peoples’ Republic of China. But Mauritania has no team sports and no sports teams, so the stadium is never used. The German government built a new hospital for Nouakchott, but it has stood empty for two years because there is no medical equipment and no beds. There are also no doctors or nurses. Mauritania does have an air force. Well, it has planes but no pilots. There are one or two pilots but they don’t fly very well. One pilot kept forgetting to put down the landing gear and sometimes landed without wheels thus ruining three planes. Yes, Nouakchott is one of the strangest capital cities in the world.

Bill Hottell, Summer 1982

|

|