home | internet service | web design | business directory | bulletin board | advertise | events calendar | contact | weather | cams

|

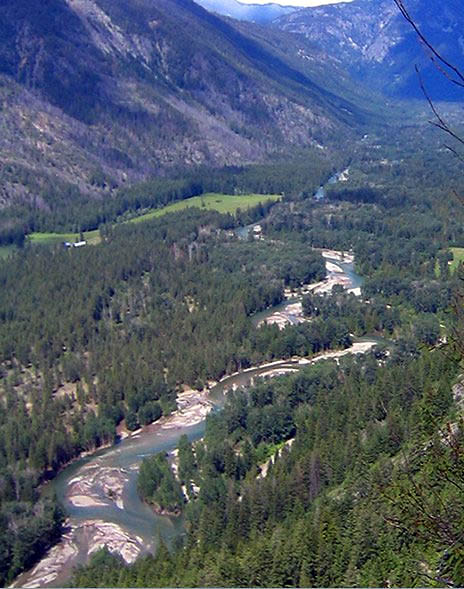

Upstream Lee Bernheisel and Lucy Reid and their Okanogan Wilderness League have left a legacy in the Methow Valley that’s hard to match.  Environmental activist Lucy Reid Environmental activist Lucy ReidDoggedly pursuing their objectives through the courts over the decades, they have made enemies and friends as they sought to protect the valley’s natural resources. They’re credited with stopping the contentious Early Winters/Arrowleaf ski resort in Mazama by pressing the state Department of Ecology to enforce existing state water law. After their prodding, Ecology concluded that there wasn’t enough legally available water in the valley’s Early Winters reach to build it. They slowed development in Twisp by successfully arguing before the Washington State Supreme Court that the town had rested on its water rights after the 1948 flood. When the town sought to use that water right five decades later, OWL argued that this would be illegal under the state’s “use it or lose it” law. The court ruled that the town had indeed relinquished its historic water right. And they successfully pursued a legal effort to make the notoriously leaky Methow Valley Irrigation District (MVID) system stop wasting water, leading to the present multi-million dollar down-sizing and upgrading of the district’s water delivery system and a severe reduction in the amount of water it can use. “I’m surprised you’re still alive,” someone displeased with their work once told them, Reid recalls. They both admit to having felt threatened by people who were angry about what they were doing, especially when they were trying to reduce logging on U.S. Forest Service lands to a sustainable yield. Reid, 63, and Bernheisel, 70, live in Carlton on nearby properties. “We’ve been together a long time but it’s worked out very well,” Reid says of their unorthodox living arrangement. Reid, who was divorced, arrived in the valley in 1981 and first bought property up the East Chewuch, where she raised alfalfa. A native of Detroit, she was trained as a registered nurse and worked for many years in Seattle. In 1989, she moved to Carlton.  Okanogan Wilderness League president Lee Bernheisel Okanogan Wilderness League president Lee BernheiselBernheisel, a Seattle native, arrived in the late 1970s from Aspen, Colo., and shortly became involved in the effort to create the Lake Chelan/ Sawtooth Wilderness. He and Reid met during a subsequent battle over sustained-yield timber harvesting on Forest Service lands. Their efforts prompted angry loggers to stage a logging truck rally to protest their efforts, according to Reid. OWL did not prevail in court in that instance. “I didn’t want to appeal because I was afraid,” Bernheisel says. But, he adds, “We won the battle” when sustainable logging practices eventually were adopted by the Forest Service. Bernheisel describes himself as a lifelong environmental activist who stayed in college for years but never graduated and who never has held a regular job. Asked what he studied, he replies: “Everything. I changed majors every year.” He was drafted three times, he adds, but each time got a deferment. When it got too expensive to keep “ski bumming” around Aspen, he says, he decided to come to the Methow Valley, which he knew from childhood visits with his parents. The Okanogan Wilderness League is not a membership organization but is incorporated as a constituency organization with just three officers, explains Bernheisel, who is its president. Peter Howard is vice president and Reid is secretary. Bernheisel figures OWL has been to court 20 to 30 times, and he and Reid pay its legal bills themselves. However, he adds, they have built up a solid enough reputation in the legal community that most of their legal work is done by attorneys who agree to do it pro bono or at cost. The secret to their legal success? “We had to look at the law and know the law better than the people who were enforcing it,” he says. And since theirs is not a membership organization, they are not obliged to go to a membership to get approval of what they want to do, he adds. “We started out suing the county but quickly realized the county was a lost cause. So we sued the state,” says Bernheisel. “We’re pretty good at this stuff because we stay the course.” Bernheisel was chair of the Methow Valley Citizens Council for a year in 1984 when that organization was battling the Early Winters ski resort. “I opted out when they went to the [U.S.] Supreme Court,” says Bernheisel. ”I thought the issue was water. They were just going into the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA,)” he says. “I knew very early that water was the Achilles’ Heel of Early Winters.”  Lee Bernheisel does not agree with a Methow Valley Watershed Council proposal to make unused water from the upper Methow Valley available downstream. Instead he feels that water should be dedicated to instream flows. Image courtesy Methow Watershed Council Lee Bernheisel does not agree with a Methow Valley Watershed Council proposal to make unused water from the upper Methow Valley available downstream. Instead he feels that water should be dedicated to instream flows. Image courtesy Methow Watershed CouncilThe Methow Valley Citizens’ Council got a mixed ruling from the high court, which affirmed that under NEPA, developers are not obliged to provide mitigation plans in environmentally sensitive locations such as the ski resort. When OWL persisted in fighting the R.D. Merrill Company’s plans for a downsized resort by challenging its water rights, members of the MVCC “were actually angry with us,” he recalls. By then, some environmental groups such as the Seattle-based Washington Environmental Council had voiced support for a downscaled resort. When Reid petitioned to get off the MVID and sink a well on her Carlton property, an inspector from Ecology came calling, she relates. He informed her that even though she seemed to hold more than one water right on her land, “You can’t have more than one water right” on one property, she recalls. But Ecology was prepared to grant Merrill the right to use several old water rights on the same property to build the resort, she says. “Which ticked me off,” she adds. “Twisp does not really have a water problem,” argues Bernheisel, who says he has been telling the town for years that its real water problem is “You have leaks.” The town has “terrible infrastructure,” he says. In recent years the town has paid $10,000 a year to MVID to reserve the right to use up to 400 acre-feet for irrigation. “That would cover all the irrigation need 10 times over,” says Bernheisel. However, the town has never needed to use a drop of that water, thanks to improved maintenance and repairs. It was important to intervene to prevent Twisp from seizing use of a water right it relinquished 50 years earlier, says Reid, because of the bad legal precedent this would set for managing in-stream river flows. So they decided they had to sue to stop it, Reid says. “You don’t want to let it pass.” The twosome lobbied the state to no avail as early as the 1980s to adjudicate water rights in each of the valley’s seven reaches; about 20 percent of the water rights in the Methow Valley are legally adjudicated, according to Bernheisel’s estimate. He reminds that it takes legal adjudication to establish a water right and that many existing valley water claims have never been legally proven up. Aside from the Early Winters reach, all the other six reaches are over-subscribed “if you calculate it on a legal basis,” says Bernheisel, who adds, “There’s no enforcement in this valley” of state water law. Asked if OWL supports the Methow Watershed Council’s pending proposal to move unused water from the Early Winters reach downstream to the towns of Twisp and Winthrop, Bernheisel answers: “I don’t agree with the project. There’s no need to do that.” Neither does he support the watershed council’s pending effort to have the legislature designate the council a legal entity empowered to move and store water. That’s because he believes its focus is on how to get around water-based restrictions on development rather than on conserving water, Bernheisel told Grist. The watershed council has released a study showing that while domestic exempt well users are allowed to use 5,000 gallons a day, most use only 700. If so, theoretically this frees up lots of water that could be used for future development in the valley. But Bernheisel argues that any excess water should be dedicated to in-stream flows. “That’s where we need it,” he argues. “If you want to make it 700 [gpm],” adds Reid, alluding to the 5,000-gallons per day exemption for domestic users, “go to the legislature and have them make it 700.” At the heart of their work, says Bernheisel, is an effort to “set some precedents. That’s what we tried to do.” 10/24/2013 Related stories: Methow Valley Irrigation District | MVID Test Well | Methow Water Study | Water Authority Proposal Comments

|